Paper: arxiv.org/html/2509.26076v1

Apparently also has human review as part of the process. Newbs. Just require Lean solutions and be done with it... They do address it in a section of the paper "Formal math benchmarks" but still meh. Review must be fully automated, none of that asking humans bullshit.

Required CharacteristicsRequires genuine insight: Not solvable by routine application of known algorithms

Example problem:

Welcome to my home page!

Welcome to my home page!

Powerful Love Spells Caster, Spiritual Healing, Black Magic Spells, Lucky And Wealthy Rituals €꧂+27672740459. by  babakagolo 0 2026-03-02

babakagolo 0 2026-03-02

A Love Spell 111 can be defined as any type of ritual, spell, or work of magic that brings about love, lust, attraction, or endearment. Love Spells Magic to help you understand your relationship problems, find your soul mate and make them fall in love with you with the help of Baba Kagolo. Save your marriage from divorce & make your relationship stronger, fix trust issues & misunderstandings between two lovers and get back your lost lover in just 48 hours. Love spells to reverse a breakup & save your relationship. Lost love spells to get your ex lost love back permanently & bring back lost love.

Heal relationship problems using love spells to increase love between two people. Love spells to banish intimacy & communication problems in your relationship. Love spells to make someone fall in love with you, attract a new lover, stop your partner from cheating on you & love spells to prevent a divorce. Love spells carry enormous powers which are not to harm but to strengthen the bond and the love two people have, or rather had, with one another. Baba Kagolo is bound to be associated with a good intention of returning love completely. He uses herbs, candles, shells, flowers, talismans, bags, voodoo vases, and the most widely used voodoo dolls to perform love spells.

*Are you in a relationship that feels one-sided?

*Are you in a marriage that is failing? If that is the case, then cast my love spells that work fast.

*Do you want to strengthen your relationship?

*Do you want to make him love you more?

*Do you feel he or she is seeing others? Are you involved in a loveless relationship?

Heal relationship problems using love spells to increase love between two people. Love spells to banish intimacy & communication problems in your relationship. Love spells to make someone fall in love with you, attract a new lover, stop your partner from cheating on you & love spells to prevent a divorce. Love spells carry enormous powers which are not to harm but to strengthen the bond and the love two people have, or rather had, with one another. Baba Kagolo is bound to be associated with a good intention of returning love completely. He uses herbs, candles, shells, flowers, talismans, bags, voodoo vases, and the most widely used voodoo dolls to perform love spells.

*Are you in a relationship that feels one-sided?

*Are you in a marriage that is failing? If that is the case, then cast my love spells that work fast.

*Do you want to strengthen your relationship?

*Do you want to make him love you more?

*Do you feel he or she is seeing others? Are you involved in a loveless relationship?

Return Lost lovers And Restore Broken Marriages Spells CALL @ +27672740459 How to Bring back Lost Love with immediate Guaranteed results IN DUBLIN- ALABAMA- BOSTON- TORONTO- PRETORIA by  babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

The Bring Back lost lover Magic love spells will retrieve your ex-lover immediately. It will make the runaway wife or husband change their mind. They will remember all about your good qualities and forget about those negative moments that led to the separation. This spell has the power to destroy the side relationship and bring back your lover instantly. Even if the separation was caused by religious, political, cultural, Bad behaviours, man-stealing or family differences, it will harmonise the situation and inculcate love. Achieve Long Lasting Marriage Using My Voodoo Marriage Love Spells. How are solid ships built? With good courtships. Although the bride and groom are 55 years old, in good financial condition and excellent professionals, it is essential not to miss a good courtship. Some people know each other and barely a month and a half and want to get married. That is a mistake: you must marry if you have passed the test of courtship. Because the process of maturation of love has a necessary sequence, and thanks to courtship, we avoid confusing what the imagination produces as an effect of love. The courtship makes it possible, on the other hand, to meet the reality of the other person. If you would like to ensure a smooth process of courtship, cast my powerful marriage love spells, and it will happen. SPELL CASTER IS here to bring back hope to those who have been disappointed by fake sangomas. Whatever situation you passed through, there has been a reason, so that one day you can be a testimony to those who go through such a situation and bring hope to their lives. So those that need help with problems such as: Financial problems, manhood problems, relationship, marriage and love problems, evil spirits at home, bad luck, court and divorce cases, bring back lost lovers or relatives and many more contact Baba Kagolo, he uses both the powers of his ancestors and prayers to solve people’s problems and to tell you your future. Are you trying to bring back your lost love or reunite with your Ex-lover but still failing in Cyprus, Botswana, Zambia, Pretoria, or Johannesburg? Are you missing the old times with your loved one, and is it a harsh reality that you cannot forget them? Are you in love with someone who doesn’t love you back? Are you hunting for him/her? Now it is the reality, who doesn’t want this kind of life? Get married to the love of your life & seal your marriage with everlasting happiness. Bring back your Lost lover in 2 -4 days with my powerful love spells. My magical love spells will do wonders in your life and change everything in 3 days. Solve Wife-husband Problems, fix Marriage and Relationship problems. Want to know about your love situation?, to bring back your man?, want to see who cheats on your husband/wife?, to restore original love in your relationship? Want to bind you with your partner?, want to divorce?, break up a relationship?, and all marriage and relationship matters plus life issues like removing bad luck, boosting your business?, checking your future, and many more +27672740459 incredible temple and leave when all your problems are solved!!!!!!!!

🔱Most Powerful Love Spells Caster, Spiritual Healing, Black Magic Spells, Lucky And Wealthy Rituals €꧂+27672740459 ψ in South Africa, UK, USA, Spain, Sweden, Canada, UAE, Ireland, Turkey, Luxembourg by  babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

Most Powerful Love Spells Caster +27672740459 From Africa, UK, USA, Spain, Sweden, Canada, UAE, Malta, Brunei, Japan, Ireland, Turkey, Luxembourg, Iceland, Norway, Australia, Qatar, Croatia, Austria, Denmark, Netherlands, Romania, Belgium, Greece, Belarus, New Zealand, Switzerland, Cyprus, Poland, Estonia, Egypt, Fiji, Wales, Bahamas, Taiwan, Indonesia, Singapore, Czech Republic, Serbia, Palau, Lithuania, Malaysia, France, Bulgaria, German, Jordan, Chile, Algeria, Zambia, Zimbabwe, Botswana, Lesotho, Italy, Philippines, Honduras, Finland, Hungary, Mexico, Macedonia, Argentina, Syria, China, Hong Kong, Myanmar, Kuwait, South Korea, Morocco, Tunisia, Libya, Sudan, San Marino, Israel.. Contact +27672740459 (Call/WhatsApp). Baba Kagolo is a gifted spiritual healer and spell caster who may sort out your issues and problems.“I cast spells”. With the help of my spiritual powers, my spell casting is done in a unique way to help with your problems. If you have been disappointed by other spell casters and healers who have failed to provide you with the results they promised you, and you’re stuck with no option for happiness. It’s never too late for your problems to be solved. It’s time to make a change in your life for the better. Don’t just sit back and think that your worst situation cannot be changed for the better, because God helps those who help themselves. Can you submit your details to me? I may be in a position to help you out. 1) DO YOU HAVE A PROBLEM IN YOUR LOVE, IS IT DETERIORATING? I think your partner is no longer interested in you. -You might think that there is no other solution. I offer solutions for all love-related problems. I can strengthen bonds in all love relationships and marriage.

1) DO YOU WANT AN EVERLASTING LOVE WITH YOUR PARTNER?

2) I may restore love and happiness when relationships break up or down.

3) I may bring back your lost love.

4) I may help you look and choose for the best suitable partner when you can’t break the cycle of loneliness.

5) I may help to keep your partner faithful and be loyal to you alone.

6) I may create an everlasting love between couples.

1) DO YOU WANT AN EVERLASTING LOVE WITH YOUR PARTNER?

2) I may restore love and happiness when relationships break up or down.

3) I may bring back your lost love.

4) I may help you look and choose for the best suitable partner when you can’t break the cycle of loneliness.

5) I may help to keep your partner faithful and be loyal to you alone.

6) I may create an everlasting love between couples.

+27672740459꙰Africa Spiritual Witchcraft Voodoo With Effective Bring Back Lost Love Spells, Spiritual Healing, Black Magic Spells, And Wealthy Rituals To Different Parts Of The World. by  babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

+27672740459 Are you getting frustrated due to the fact that you badly need your ex-lover to regain the love for you so that you can get back together? Would you want to restore the lost love and love each other equally? If that is the case, a lost love spell is one of a kind, which is centred on resolving the love problems, giving you the best chance to get your lost lover back with you for good in a relationship with you once again.

Casting the lost love spell is an effective way of getting your lost lover back for good, ex-husband or ex-wife back with you and avoiding any nasty drama in the process. For instance, you might find that your ex-partner is now in a relationship with someone else. And other Spells like Magic Wealth Spells, Sandawana Oil, Protection Spells, Smudging, Curse Remove, Palm Reading, Psychic Reading, Protection Spells, Lottery Spells, Good luck Spells, Fortune Telling, Mediums, Beauty Spells, Spiritual Counselling, Addiction Therapy, Remove Curse Spells, Remove Negative energy, Sexual Attraction Spells, Removing Curse Spells, Witch doctor, Spiritual Cleansig, African witchcraft, hex removal, spiritual healing, Wicca, Witchcraft, Voodoo, spells, good luck charm, love spells, lucky charms, good luck, Wicca spells, Voodoo dolls.

If you have been disappointed by other spell casters and healers who have failed to provide you with the results they promised you, and you’re stuck with no option for happiness. It’s never too late for your problems to be solved. It’s time to make a change in your life for the better. Don’t just sit back and think that your worst situation cannot be changed for the better, because God helps those who help themselves.

This is a very positive get your lost lover back with you for good spell, and it is cast only when you are fueled by positive motives. If you truly believe that the person you let go is your soul mate, then there is nothing that can hinder you from casting this lost love spell. It is no crime to transcend your wishes to the one you love through a magic spell. It is the work of the lost love spell to make your wishes become the commands for your lost lover to get back with you for good has to obey.

Lost love spell, as you can call it, is just a way of calling a spell specifically cast to get your lost lover back with you and restore the love lost bond between the two couples. It doesn’t matter the kind of love magic you want to use while casting the lost love spell, but the intent is the only one that matters the most. That is why Baba Kagolo usually uses voodoo magic in most of his spells Contact +27672740459 (Call/WhatsApp), but when he is casting the lost love spell specifically, he adds some of the black magic rituals so that the get your lost lover back with you for good spell can have a little bit of aggressiveness and perfection.

Casting the lost love spell is an effective way of getting your lost lover back for good, ex-husband or ex-wife back with you and avoiding any nasty drama in the process. For instance, you might find that your ex-partner is now in a relationship with someone else. And other Spells like Magic Wealth Spells, Sandawana Oil, Protection Spells, Smudging, Curse Remove, Palm Reading, Psychic Reading, Protection Spells, Lottery Spells, Good luck Spells, Fortune Telling, Mediums, Beauty Spells, Spiritual Counselling, Addiction Therapy, Remove Curse Spells, Remove Negative energy, Sexual Attraction Spells, Removing Curse Spells, Witch doctor, Spiritual Cleansig, African witchcraft, hex removal, spiritual healing, Wicca, Witchcraft, Voodoo, spells, good luck charm, love spells, lucky charms, good luck, Wicca spells, Voodoo dolls.

If you have been disappointed by other spell casters and healers who have failed to provide you with the results they promised you, and you’re stuck with no option for happiness. It’s never too late for your problems to be solved. It’s time to make a change in your life for the better. Don’t just sit back and think that your worst situation cannot be changed for the better, because God helps those who help themselves.

This is a very positive get your lost lover back with you for good spell, and it is cast only when you are fueled by positive motives. If you truly believe that the person you let go is your soul mate, then there is nothing that can hinder you from casting this lost love spell. It is no crime to transcend your wishes to the one you love through a magic spell. It is the work of the lost love spell to make your wishes become the commands for your lost lover to get back with you for good has to obey.

Lost love spell, as you can call it, is just a way of calling a spell specifically cast to get your lost lover back with you and restore the love lost bond between the two couples. It doesn’t matter the kind of love magic you want to use while casting the lost love spell, but the intent is the only one that matters the most. That is why Baba Kagolo usually uses voodoo magic in most of his spells Contact +27672740459 (Call/WhatsApp), but when he is casting the lost love spell specifically, he adds some of the black magic rituals so that the get your lost lover back with you for good spell can have a little bit of aggressiveness and perfection.

Powerful Love Spells +27672740459 Bring Lost ❤️Love Back Spells, Traditional Healings, Witchcraft In Canada, The USA, Europe, And Africa. by  babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

✆+27672740459 Black magic expert and voodoo love spell that works overnight to retrieve that love | lost love spell caster with powerful love psychic reading. The best spellcaster in Clarksville to renew your relationship & make your relationship stronger. Love spells to bring back the feelings of love for ex-lovers. Increase the intimacy, affection & love between you and your lover using voodoo relationship love spells in the USA. Money spells, easy love spells with just words, think of me spells, powerful love spells, spells of love, spells that work, love potion to attract a man, easy love spells with just words, pink candle prayer, white magic spells, call me spell, manifestation spell, gay love spells, Commitment spells, business spells and, how to bring back lost love in a relationship, Witchcraft love spells that work immediately to increase love & intimacy in your relationship. Attraction love spells to attract someone, stop a divorce, prevent a breakup & get your ex back. When using magic spells, there are several things you should know, particularly how to protect yourself from negative energies and how to use the powers of chants for the good of all people involved. When the focus is love, the results are truly magical. It's important to remember that love is not manipulative, it is not forceful, and it does not bend another to its will. +27672740459📁︎⋑ Remove Black Magic in Cape Town, Return Lost Love in Johannesburg, Fix Relationships in Durban, Break Ups Spells in Pretoria, Fix Enemies Spells in Gqeberha, Win Divorce Cases in Bloemfontein, Stop Cheating in East London, Gay & Lesbian Love Spells in Soweto, Have babies Spells in Pietermaritzburg, Fortune Telling in Charlotte, Spiritual Counselling in Seattle, Remove Curse Spells in Boston, Remove Negative Energy in Dallas, Sexual Attraction Spells in Los Angeles, Removing Curse Spells in Chicago, Witchdoctor in New York, Spiritual Cleansing in San Francisco, African witchcraft in Austin, hex removal in Vancouver, spiritual healing in Toronto, Wicca in Québec City, Witchcraft in St. John's, Voodoo spells in Calgary, good luck charm in Ottawa, love spells in Edmonton, lucky charms in Winnipeg, good luck in Montreal, Wicca spells in Canberra, Voodoo dolls in Sydney. Love is free-flowing, accepting, kind, and generous. You must have good intentions for your love spell to work as intended. Below, we share the top five love spells you can use today to shift the energies in your life and create a future filled with love and fulfilment. Obsession Love Spells to Get Your Ex-Lover Back. All women want one thing the most in life: to be loved and love in return – not much to ask. A lady wants a good man who loves you unconditionally and is loyal. You want a man who is honest, hardworking, and loyal – not a complainer, a weakling or a self-centred man. You are a strong, independent, sensual, caring, loving woman. And you don't think it's asking too much to want to be with a loving, intelligent man with a good sense of humour and daring, an upright and confident man – who knows who he is. No one wants a chauvinistic and macho man, but you want someone willing to protect and care for you. Who loves you for you and not some imaginary one? You do not doubt that when the right guy appears on your doorstep, you'll never let him go. But sometimes a man doesn't realise he has that good woman. ☎️ Call: ✺ +27672740459✺ ✍️ WhatsApp Now.

Instant love Spells Caster ༺|༻ +27672740459 Bring Back Lost love SPELLS CASTER, Sweden Switzerland, Taiwan, South Africa, Turkey, The USA. by  babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

Are you struggling in your relationship? Relationships and marriage can be difficult at times. Do you feel like your relationships and/or marriage are in turmoil? I understand how hard these times can be, but don't give up hope. My team of experienced healers are dedicated to helping couples rebuild trust, strengthen their relationship, and reconnect with each other. Get customised love spells and personalised psychic readings to clear all your obstacles and find the answers you are looking for. I am very straightforward and always help people to meet reality, no matter how harsh it is. I use the best of my knowledge to guide people on how to walk on the right track. My area of specialisation includes Numerology, Gemology, Palmistry, Love Psychic Readings, Lal Kitab Remedies, Black Magic Removal, Negative Energy Removal and Evil Spirit Removal Solutions. Lost Love spells are very effective and work fast for both opposite sex and same sex couples. Be serious that the people you want to cast this spell upon, you love him or her. Bring back your lost love today with the help of these bring back lost love spells that work fast. Even if you lost your lover 2 years or 4 years ago, with the help of these love spells, he or she will be back. These spells are very powerful. If you would like to bring back the love of your life? This bring back lost love spell is a must. Marriage Love Spells. Is your lover not taking you seriously? Are you tired of being single? Have you stayed with your lover for so many years? He or she doesn’t want to propose to you. Marriage love spells are a must for you. To decide about casting these spells. You must clear your mind and make the right decision. Honeymoon love spells. If you like your lover to take you on a honeymoon? This spell is right for you. After casting this spell, your love will automatically be in the mood to take you on a honeymoon. Expect very effective results. Honeymoon Love spells are very powerful, and they also strengthen your relationship.

Love Spells Caster【+27672740459】⭆ Most Effective Love Spells, Powerful Bring Back Lost Love Spells, Spiritual Healing, Money Rituals © In 24 Hours In USA, Chicago, Johannesburg, Toronto, Michigan. by  babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

babakagolo 0 2026-02-28

+27672740459 SPELL CASTER/ LUCK TO HELP YOU GET BACK YOUR EX-LOVER IN ONE DAY CALL Baba Kagolo^^^^@@@ IN SOUTH AFRICA

We need a lost love spell caster, a love specialist, a voodoo spells caster, a witch doctor, a native healer, a spiritual healer, a traditional doctor, and a black magician. Do you need a spell caster? Looking for a love spells caster? How to get a spell caster? Do you want a spell caster within? Need to bring back your lost lover? Do you want your lost lover back? Do you need your ex to return? Do you want your ex to return? I need a love spells caster / a spell caster to bring back a lost lover, return reunite ex-boyfriend girlfriend wife husband? I am an international based in South Africa online traditional healer, a spell caster, a spiritual healer, astrologer, a psychic, black magician and love healing expert, a love spell caster to bring back your lost lover in Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Virginia Washington dc, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, American Samoa, District of Columbia, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands. I can bring back your ex-lover, lost lover, ex-girlfriend, girlfriend, ex-boyfriend, boyfriend, ex-wife, wife, ex-husband husband. I am a true love specialist in spell healing. I am real, best and good love spells caster/voodoo spells caster/a spell caster in Miami Michigan Chicago. I am a lost love voodoo spell caster/ a lost love spell caster/a lost love psychic. I practice spell healing and spiritual healing that work immediately within and around. I am a traditional doctor. A witch doctor a native healer a traditional herbalist and a spiritual healer. I am a traditional fortune teller. I have authentic spell healing powers to work faster, my voodoo spell healing power returns and reunites ex-lover in 2 days. I am the spell caster to Bring Back a Lost Lover Even If lost for a Long Time. I practice quick spiritual spell power that works instantly on your fiancé. And other Spells like Magic Wealth Spells, Sandawana Oil, Protection Spells, Smudging, Curse Remove, Palm Reading, Psychic Reading, Protection Spells, Lottery Spells, Good luck Spells, Fortune Telling, Mediums, Beauty Spells, Spiritual Counselling, Addiction Therapy, Remove Curse Spells, Remove Negative energy, Sexual Attraction Spells, Removing Curse Spells, Witch doctor, Spiritual Cleansig, African witchcraft, hex removal, spiritual healing, Wicca, Witchcraft, Voodoo, spells, good luck charm, love spells, lucky charms, good luck, Wicca spells, Voodoo dolls, powerful love spells, break up spells, magic love spells, Sangoma, traditional medicine, Love Spell That Work. ☎️ Call: ✺ +27672740459✺ ✍️ WhatsApp Now. Do You Want to Win a Court Case or Tenders?

We need a lost love spell caster, a love specialist, a voodoo spells caster, a witch doctor, a native healer, a spiritual healer, a traditional doctor, and a black magician. Do you need a spell caster? Looking for a love spells caster? How to get a spell caster? Do you want a spell caster within? Need to bring back your lost lover? Do you want your lost lover back? Do you need your ex to return? Do you want your ex to return? I need a love spells caster / a spell caster to bring back a lost lover, return reunite ex-boyfriend girlfriend wife husband? I am an international based in South Africa online traditional healer, a spell caster, a spiritual healer, astrologer, a psychic, black magician and love healing expert, a love spell caster to bring back your lost lover in Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Tennessee, South Dakota, Utah, Vermont, Virginia Washington dc, West Virginia, Wisconsin, Wyoming, American Samoa, District of Columbia, Guam, Northern Mariana Islands, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands. I can bring back your ex-lover, lost lover, ex-girlfriend, girlfriend, ex-boyfriend, boyfriend, ex-wife, wife, ex-husband husband. I am a true love specialist in spell healing. I am real, best and good love spells caster/voodoo spells caster/a spell caster in Miami Michigan Chicago. I am a lost love voodoo spell caster/ a lost love spell caster/a lost love psychic. I practice spell healing and spiritual healing that work immediately within and around. I am a traditional doctor. A witch doctor a native healer a traditional herbalist and a spiritual healer. I am a traditional fortune teller. I have authentic spell healing powers to work faster, my voodoo spell healing power returns and reunites ex-lover in 2 days. I am the spell caster to Bring Back a Lost Lover Even If lost for a Long Time. I practice quick spiritual spell power that works instantly on your fiancé. And other Spells like Magic Wealth Spells, Sandawana Oil, Protection Spells, Smudging, Curse Remove, Palm Reading, Psychic Reading, Protection Spells, Lottery Spells, Good luck Spells, Fortune Telling, Mediums, Beauty Spells, Spiritual Counselling, Addiction Therapy, Remove Curse Spells, Remove Negative energy, Sexual Attraction Spells, Removing Curse Spells, Witch doctor, Spiritual Cleansig, African witchcraft, hex removal, spiritual healing, Wicca, Witchcraft, Voodoo, spells, good luck charm, love spells, lucky charms, good luck, Wicca spells, Voodoo dolls, powerful love spells, break up spells, magic love spells, Sangoma, traditional medicine, Love Spell That Work. ☎️ Call: ✺ +27672740459✺ ✍️ WhatsApp Now. Do You Want to Win a Court Case or Tenders?

Welcome to my home page!

Welcome to my home page!

Best Crypto Recovery Services consult OPTIMISTIC HACKER GAIUS

I am beyond grateful to Optimistic Hacker Gaius for recovering my scammed crypto. After losing a significant amount to a sophisticated scam, I thought all hope was lost. But Gaius stepped in, explained the process, and worked tirelessly to track and recover my funds. His professionalism and expertise were evident throughout. Thanks to him, I got everything back. If you're in a similar situation, I highly recommend reaching out to Gaius. Truly a lifesaver!"

CONTACT INF.......

MAIL BOX: support @optimistichackargaius.co.m

WHATSapp: +44 737 674 0569

Welcome to my home page!

Welcome to my home page!

Welcome to my home page!

Welcome to my home page!

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

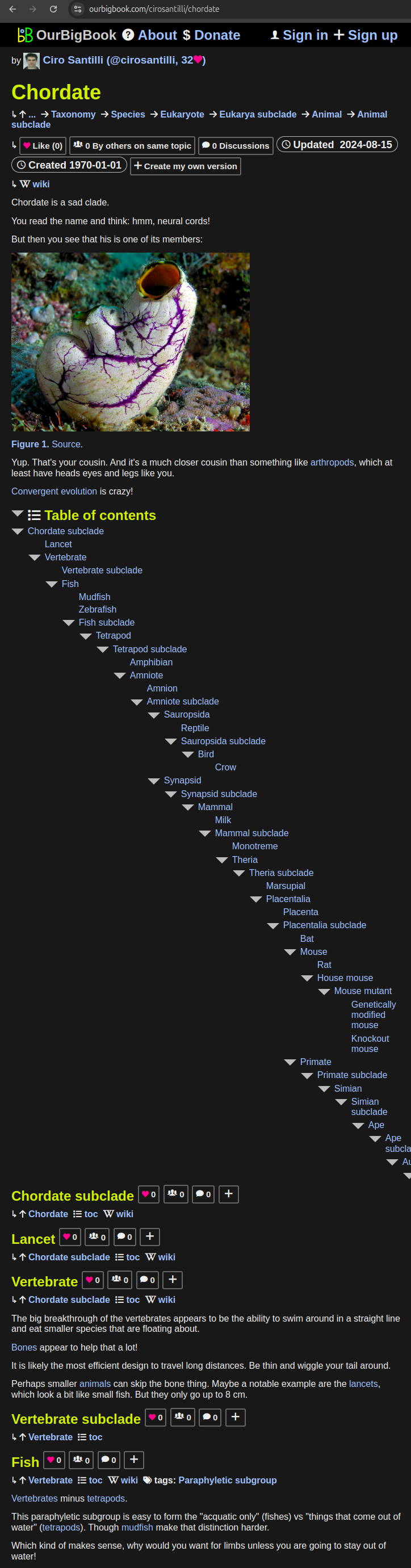

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

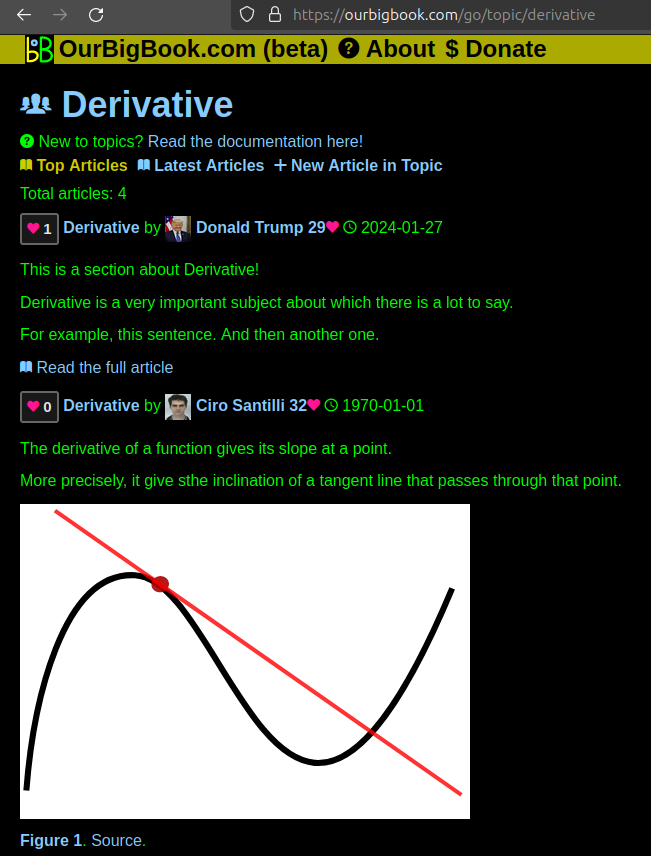

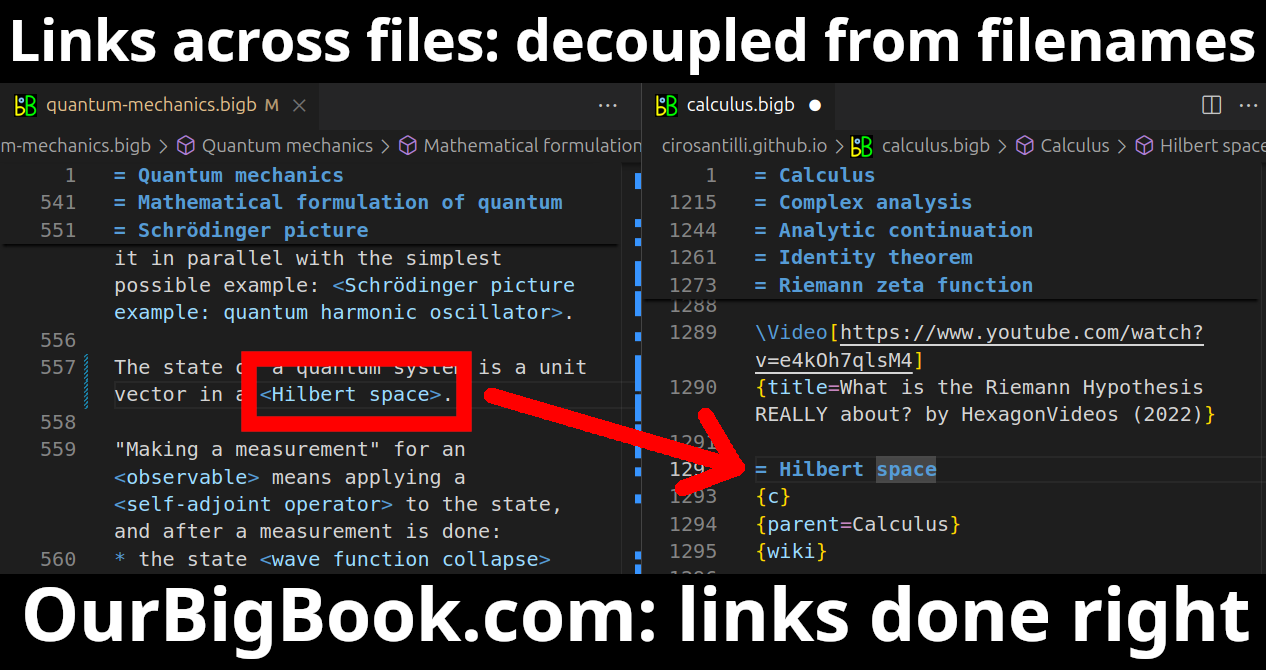

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

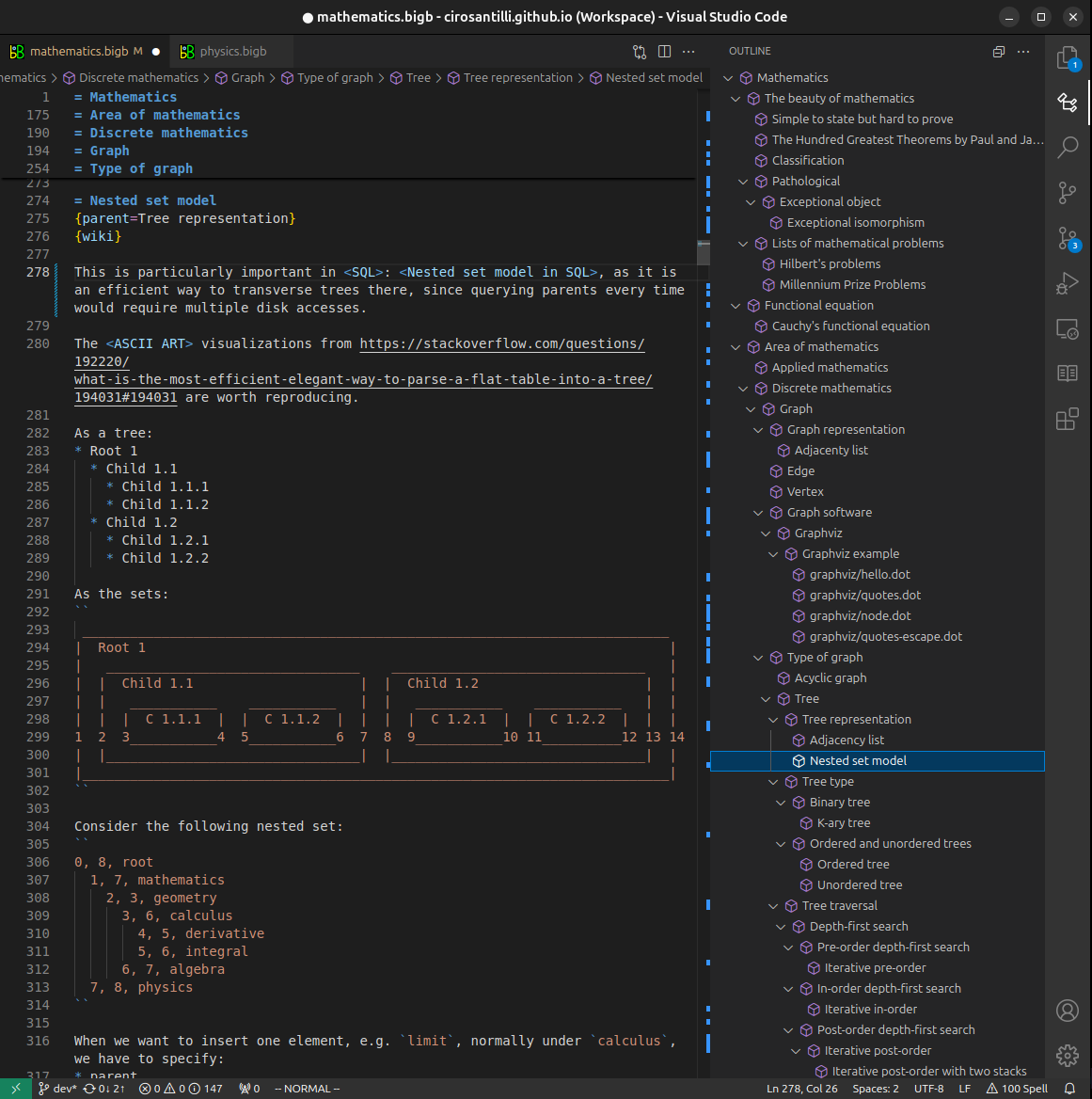

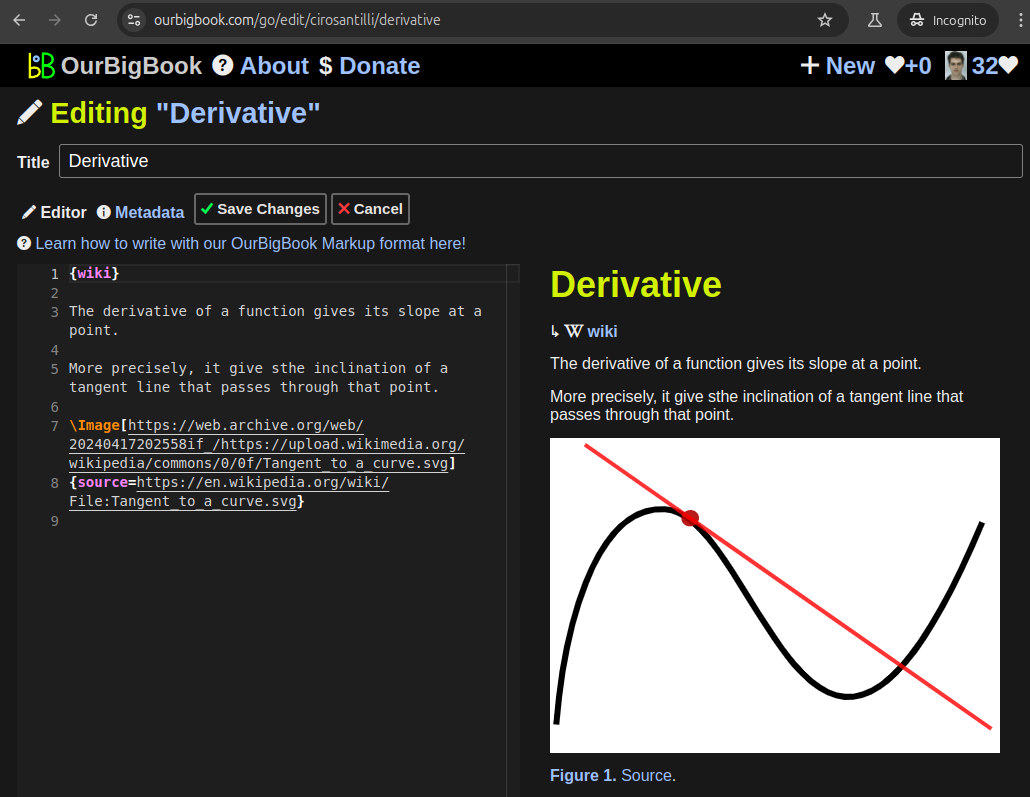

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact