The fundamental insight of Git design is: a SHA represents not only current state, but also the full history due to the Merkle tree implementation, see notably:

This makes it so that you will always notice if you are overwriting history on the remote, even if you are developing from two separate local computers (or more commonly, two people in two different local computers) and therefore will never lose any work accidentally.

It is very hard to achieve that without the Merkle tree.

Consider for example the most naive approach possible of marking versions with consecutive numbers:

If Local 1 were to push to Remote first, how could Local 2 notice that when it tries to push itself? The navie method of just checking: "does Remote have commit "2"" does not work, because Local 2 has a different version of commit 2 than local 1.

- stackoverflow.com/questions/600079/how-do-i-clone-a-subdirectory-only-of-a-git-repository/52269934#52269934

- summaries:

- dupes:

- file or directory

- file

- only small files:

Perfect Git integration belongs in integrated development environments :-)

This is good. But it misses some key operations, so much so that makes Ciro not want to learn/use it daily.

This is where Ciro Santilli stored his code since he started coding nonstop in 2013.

He does not like the closed source aspect of it, but hey, there are more important things to worry about, the network effect is just too strong.

The cheapest and most resilient way to publish text content humanity has achieved so far.

Some tests:

- github.com/cirosantilli/jekyll-cheat: cirosantilli.com/jekyll-cheat

- github.com/cirosantilli/test-gh-pages-min: cirosantilli.com/test-gh-pages-min. Minimal version of the above.

The heart/main innovation of GitHub!

See also: Ciro Santilli's minor projects.

This is a quick presentation that goes over some of the most common difficulties people find with Git.

This is the most important thing to understand Git!

You must:

- be able to visualize the commit tree

- understand how each git command modifies the commit DAG

But not every directed acyclic graph is a tree.

Example of a tree (and therefore also a DAG):Convention in this presentation: arrows implicitly point up, just like in a

5

|

4 7

| |

3 6

|/

2

|

1git log, i.e.:and so on.Example of a DAG that is not a tree:This is not a tree because there are two ways to reach 7:

7

|\

4 6

| |

3 5

|/

2

|

1Example of a graph that is not a DAG:This one is not acyclic because there is a cycle 2, 3, 4, 5, 2.

6

^

|

3->4

^ |

| v

2<-5

^

|

1It can even have more than 2, there's no limit. Although that is not so common (with good reason, 2 is already one too many): softwareengineering.stackexchange.com/questions/314215/can-a-git-commit-have-more-than-2-parents/377903#377903

Some people like merges, but they are ugly and stupid. Rebase instead and keep linear history.

Linear history:

5 master

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

1 first commitBranched history:

7 master

|\

| \

6 \

|\ \

| | |

3 4 5

| | |

| / /

|/ /

2 /

| /

1/ first commitWhich type of tree do you think will be easier to understand and maintain?

????

????????????

You may disconnect now if you still like branched history.

Generate a minimal test repo. You should get in the habit of doing this to test stuff out.

#!/usr/bin/env bash

mkdir git-tips

cd git-tips

git init

for i in 1 2 3 4 5; do

echo $i > f

git add f

git commit -m $i

done

git checkout HEAD~2

git checkout -b my-feature

for i in 6 7; do

echo $i > f

git add f

git commit -m $i

doneFor the newbs.

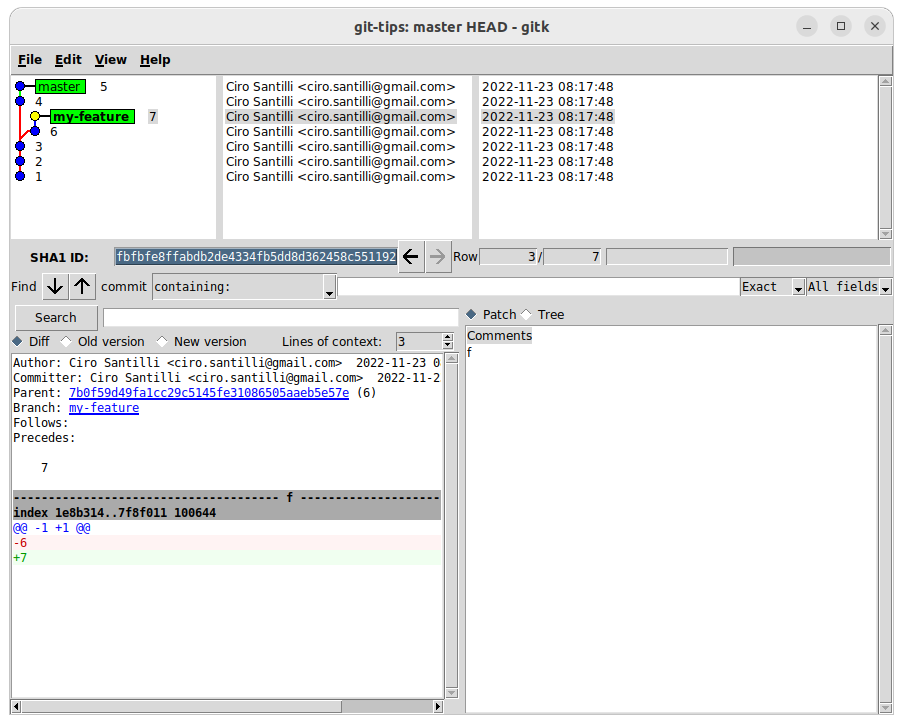

Slick? No. But gitk does the job, like any one of the other 100 billion free Git UI viewers out there

gitk master HEADMany IDEs are also implementing this now (e.g. VS Code, Eclipse. Most free IDE GIt implementations are still crap, but that is the future, because you want to edit, view history, edit, view history, commit, edit.

For the strong.

git log --abbrev-commit --decorate --graph --pretty=oneline master HEADOutput:

* b4ec057 (master) 5

* 0b37c1b 4

| * fbfbfe8 (HEAD -> my-feature) 7

| * 7b0f59d 6

|/

* 661cfab 3

* 6d748a9 2

* c5f8a2c 1If we also add the As we can see, this removes any commit that is neither:

--simplify-by-decoration, which you very often want want on a real repository with many commits:* b4ec057 (master) 5

| * fbfbfe8 (HEAD -> my-feature) 7

|/

* c5f8a2c 1- under a branch or tag

- at the intersection of too branches or tags

Option 1)

git commit. Doh!!!Option 2)

git rebase. Basically allows you to do arbitrary modifications to the tree. The most important ones are:Before:

5 master

|

4 7 my-feature HEAD

| |

3 6

|/

2

|

1Action:

git rebaseAfter:Ready to push with linear history!

7 my-feature HEAD

|

6

|

5 master

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

1Before:

7 my-feature HEAD

|

6

|

5 master

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

1Oh, commit 6 was crap:

git rebase -i HEAD~2Mark

6 to be modified.After:Better now, ready to push.

7 my-feature HEAD

|

6v2

|

5 master

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

1Note: history changes change all commits SHAs. All parents are considereEven time is considered. So is commit message/author. And obviously file contents. So now commit "7" will actually have a different SHA.

Before

7 my-feature HEAD

|

6

|

5 master

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

1Mark

6 to be squashed.After:Better now, ready to push.

67 my-feature HEAD

|

5 master

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

1Oh but there are usually 2 trees: local and remote.

So you also have to learn how to observe and modify and sync with the remote tree!

But basically:to update the remote tree. And then you can use it exactly like any other branch, except you prefix them with the remote (usually

git fetchorigin/*), e.g.:origin/masteris the latest fetch of the remote version ofmasterorigin/my-featureis the latest fetch of the remote version ofmy-feature

In order to solve conflicts, you just have to understand what commit you are trying to move where.

E.g. if from:we do:what happens step by step is first 6 is moved on top of 5:and then 7 is moved on top of the new 6:

5 master

|

4 7 my-feature HEAD

| |

3 6

|/

2

|

1git rebase master6on5 HEAD

|

5 master

|

4 7 my-feature

| |

3 6

| |

2-----------------+

|

17on5 HEAD

|

6on5

|

5 master

|

4 7 my-feature

| |

3 6

| |

2-----------------+

|

17on5 my-feature HEAD

|

6on5

|

5 master

|

4

|

3

|

2

|

1The key to solve conflicts is:

You have to understand what are the two commits that touched a given line (one from master, one from features), and then combine them somehow.

Or in other words, at every rebase conflict we have something like:Therefore there are 2 diffs that you have to understand and reconcile:

master-commit feature-commit

| |

| |

base-commit------+

|

|base-committomaster-commitbase-committofeature-commit

diff3 conflict is basically what you always want to see, either by setting it as the default as per stackoverflow.com/questions/27417656/should-diff3-be-default-conflictstyle-on-git:git config --global merge.conflictstyle diff3git checkout --conflict=diff3With this, conflicts now show up as:

++<<<<<<< HEAD

+5

++||||||| parent of 7b0f59d (6)

++3

++=======

+ 6

++>>>>>>> 7b0f59d (6)7b0f59d is the SHA-2 of commit 6.instead of the inferior default:

++<<<<<<< ours

+5

++=======

+ 6

++>>>>>>> theirsWe can also observe the current tree state during resolution:so we understand that we are now at 5 and that we are trying to apply our commit

* b4ec057 (HEAD, master) 5

* 0b37c1b 4

| * fbfbfe8 (my-feature) 7

| * 7b0f59d 6

|/

* 661cfab 3

* 6d748a9 2

* c5f8a2c 16So it is much clearer what is happening:and so now we have to decide what the new code is that will put both of these together.

We now reach:and the tree looks like:So we understand that:

++<<<<<<< HEAD

+11

++||||||| parent of fbfbfe8 (7)

++6

++=======

+ 7

++>>>>>>> fbfbfe8 (7)* ca7f7ff (HEAD) 6

* b4ec057 (master) 5

* 0b37c1b 4

| * fbfbfe8 (my-feature) 7

| * 7b0f59d 6

|/

* 661cfab 3

* 6d748a9 2

* c5f8a2c 1and after resolving that one we now reach:

* e1aaf20 (HEAD -> my-feature) 7

* ca7f7ff 6

* b4ec057 (master) 5

* 0b37c1b 4

* 661cfab 3

* 6d748a9 2

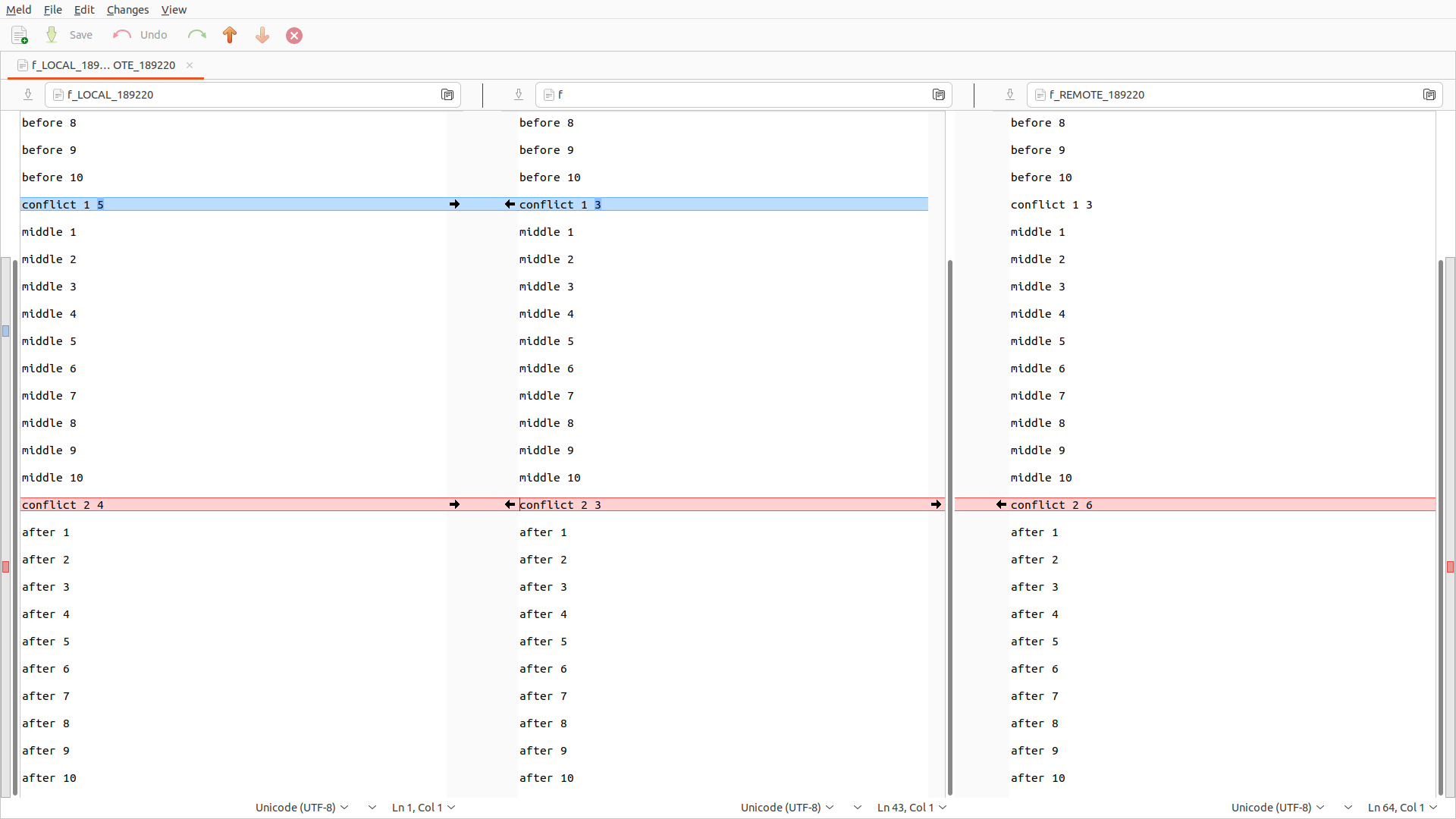

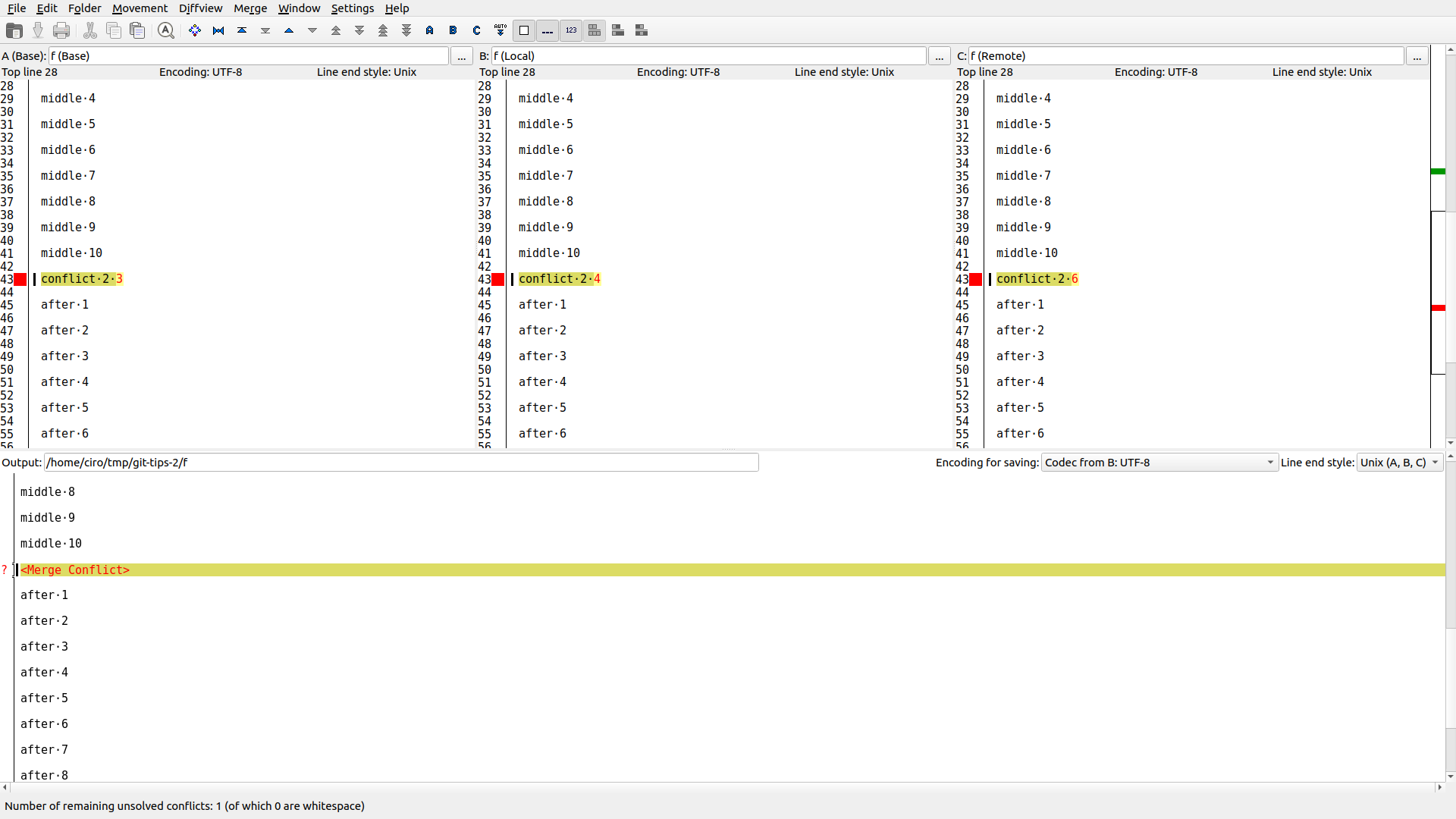

* c5f8a2c 1These are good free newbie GUI options:

sudo apt install meld

git mergetool --tool meld

sudo apt install kdiff3

git mergetool --tool kdiff3git-tips-2.sh

#!/usr/bin/env bash

set -eux

add() (

rm -f f

for i in `seq 10`; do

printf "before $i\n\n" >> f

done

printf "conflict 1 $1\n\n" >> f

for i in `seq 10`; do

printf "middle $i\n\n" >> f

done

printf "conflict 2 $2\n\n" >> f

for i in `seq 10`; do

printf "after $i\n\n" >> f

done

git add f

)

rm -rf git-tips-2

mkdir git-tips-2

cd git-tips-2

git init

for i in 1 2 3; do

add $i $i

git commit -m $i

done

add 3 4

git commit -m 4

add 5 4

git commit -m 5

git checkout HEAD~2

git checkout -b my-feature

add 3 6

git commit -m 6

add 7 6

git commit -m 7git rebase does not tell you that, and that sucks.We only know which commit from the feature branch caused the problem.

Generally we can guess or it is not needed, but

imerge does look promising: stackoverflow.com/questions/18162930/how-can-i-find-out-which-git-commits-cause-conflicts Articles by others on the same topic

There are currently no matching articles.