There are infinitely many conjectures asking if such types of primes also form infinite families.

Usually the answer is yes, but no one was able to prove it yet.

Collaborative mega list: math.stackexchange.com/questions/4523193/are-there-infinitely-many-primes-of-the-form-x-we-probably-dont-know

There are infinitely many prime k-tuples for every admissible tuple.

Generalization of the Twin prime conjecture.

As of 2023, there was no specific admissible tuple for which it had been proven that there infinite of, only bounds of type:But these do not specify which specific tuple, e.g. Yitang Zhang's theorem.

There are infinitely many primes with a neighbor not further apart than 70 million. This was the first such finite bound to be proven, and therefore a major breakthrough.

This implies that for at least one value (or more) below 70 million there are infinitely many repetitions, but we don't know which e.g. we could have infinitely many:or infinitely many:or infinitely many:or infinitely many:but we don't know which of those.

The Prime k-tuple conjecture conjectures that it is all of them.

Also, if 70 million could be reduced down to 2, we would have a proof of the Twin prime conjecture, but this method would only work for (k, k + 2).

Let's show them how it's done with primes + awk. Edit. They have a gives us the list of all twin primes up to 100:Tested on Ubuntu 22.10.

-d option which also shows gaps!!! Too strong:sudo apt install bsdgames

primes -d 1 100 | awk '/\(2\)/{print $1 - 2, $1 }'0 2

3 5

5 7

11 13

17 19

29 31

41 43

59 61

71 73Consider this is a study in failed computational number theory.

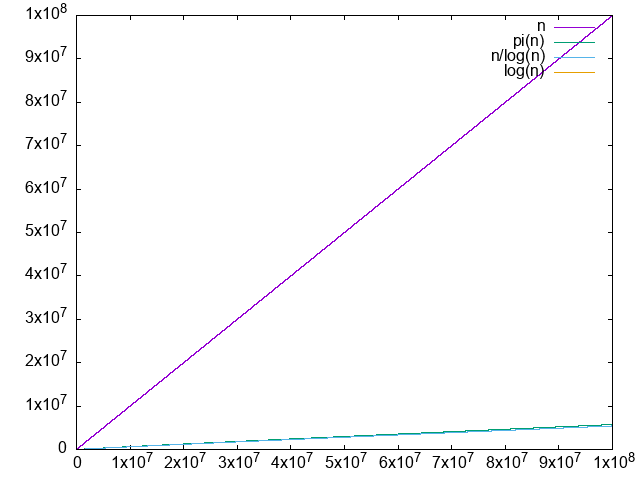

The approximation converges really slowly, and we can't easy go far enough to see that the ration converges to 1 with only awk and primes:Runs in 30 minutes tested on Ubuntu 22.10 and P51, producing:

sudo apt intsall bsdgames

cd prime-number-theorem

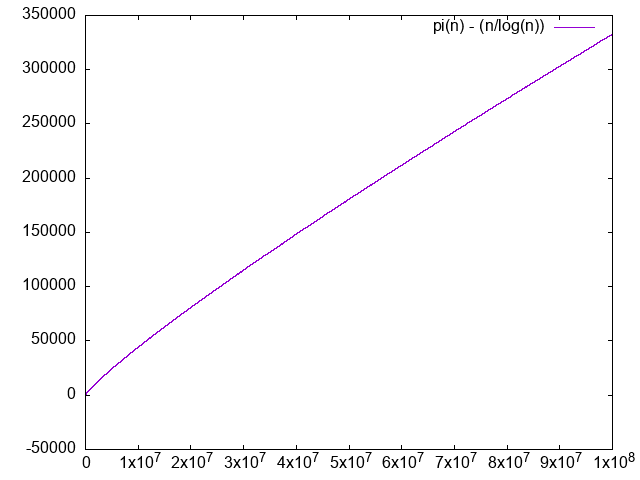

./main.py 100000000. It is clear that the difference diverges, albeit very slowly.

. We just don't have enough points to clearly see that it is converging to 1.0, the convergence truly is very slow. The logarithm integral approximation is much much better, but we can't calculate it in awk, sadface.

But looking at: en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Prime_number_theorem_ratio_convergence.svg we see that it takes way longer to get closer to 1, even at it is still not super close. Inspecting the code there we see:so OK, it is not something doable on a personal computer just like that.

(* Supplement with larger known PrimePi values that are too large for \

Mathematica to compute *)

LargePiPrime = {{10^13, 346065536839}, {10^14, 3204941750802}, {10^15,

29844570422669}, {10^16, 279238341033925}, {10^17,

2623557157654233}, {10^18, 24739954287740860}, {10^19,

234057667276344607}, {10^20, 2220819602560918840}, {10^21,

21127269486018731928}, {10^22, 201467286689315906290}, {10^23,

1925320391606803968923}, {10^24, 18435599767349200867866}};Polynomial time for most inputs, but not for some very rare ones. TODO can they be determined?

But it is better in practice than the AKS primality test, which is always polynomial time.

The "greatest common divisor" of two integers and , denoted is the largest natural number that divides both of the integers.

For example, is 4, because:

Articles by others on the same topic

A prime number is a natural number greater than 1 that has no positive divisors other than 1 and itself. In other words, a prime number is only divisible by 1 and the number itself, meaning it cannot be divided evenly by any other integers. For example, the numbers 2, 3, 5, 7, 11, and 13 are all prime numbers.