Boltzmann constant Updated 2025-07-16

This is not a truly "fundamental" constant of nature like say the speed of light or the Planck constant.

Rather, it is just a definition of our Kelvin temperature scale, linking average microscopic energy to our macroscopic temperature scale.

The way to think about that link is, at 1 Kelvin, each particle has average energy:per degree of freedom.

For an ideal monatomic gas, say helium, there are 3 degrees of freedom. so each helium atom has average energy:

Another conclusion is that this defines temperature as being proportional to the total energy. E.g. if we had 1 helium atom at 2 K then we would have about energy, 3 K and so on.

This energy is of course just an average: some particles have more, and others less, following the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution.

Fe-C Updated 2025-07-16

Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution Updated 2025-07-16

Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution for three different temperatures

. Maxwell-Boltzmann vs Bose-Einstein vs Fermi-Dirac statistics Created 2024-10-28 Updated 2025-07-16

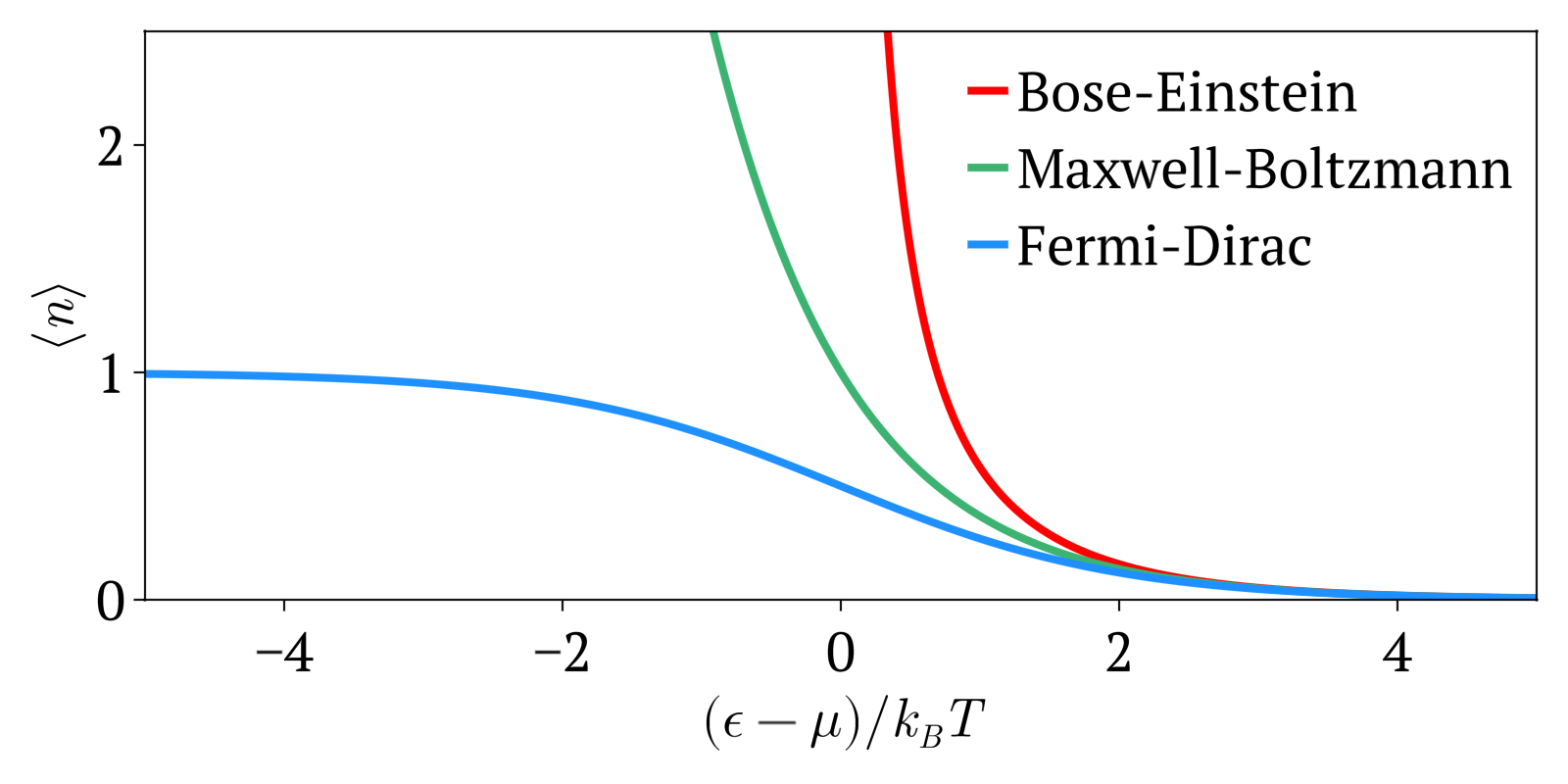

Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics, Bose-Einstein statistics and Fermi-Dirac statistics all describe how energy is distributed in different physical systems at a given temperature.

For example, Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics describes how the speeds of particles are distributed in an ideal gas.

The temperature of a gas is only a statistical average of the total energy of the gas. But at a given temperature, not all particles have the exact same speed as the average: some are higher and others lower than the average.

For a large number of particles however, the fraction of particles that will have a given speed at a given temperature is highly deterministic, and it is this that the distributions determine.

One of the main interest of learning those statistics is determining the probability, and therefore average speed, at which some event that requires a minimum energy to happen happens. For example, for a chemical reaction to happen, both input molecules need a certain speed to overcome the potential barrier of the reaction. Therefore, if we know how many particles have energy above some threshold, then we can estimate the speed of the reaction at a given temperature.

The three distributions can be summarized as:

- Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics: statistics without considering quantum statistics. It is therefore only an approximation. The other two statistics are the more precise quantum versions of Maxwell-Boltzmann and tend to it at high temperatures or low concentration. Therefore this one works well at high temperatures or low concentrations.

- Bose-Einstein statistics: quantum version of Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics for bosons

- Fermi-Dirac statistics: quantum version of Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics for fermions. Sample system: electrons in a metal, which creates the free electron model. Compared to Maxwell-Boltzmann statistics, this explained many important experimental observations such as the specific heat capacity of metals. A very cool and concrete example can be seen at youtu.be/5V8VCFkAd0A?t=1187 from Video "Using a Photomultiplier to Detect single photons by Huygens Optics" where spontaneous field electron emission would follow Fermi-Dirac statistics. In this case, the electrons with enough energy are undesired and a source of noise in the experiment.

A good conceptual starting point is to like the example that is mentioned at The Harvest of a Century by Siegmund Brandt (2008).

Consider a system with 2 particles and 3 states. Remember that:

- in quantum statistics (Bose-Einstein statistics and Fermi-Dirac statistics), particles are indistinguishable, therefore, we might was well call both of them

A, as opposed toAandBfrom non-quantum statistics - in Bose-Einstein statistics, two particles may occupy the same state. In Fermi-Dirac statistics

Therefore, all the possible way to put those two particles in three states are for:

- Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution: both A and B can go anywhere:

- Bose-Einstein statistics: because A and B are indistinguishable, there is now only 1 possibility for the states where A and B would be in different states.

- Fermi-Dirac statistics: now states with two particles in the same state are not possible anymore:

Nuclear magnetic resonance Updated 2025-07-16

Ciro Santilli once visited the chemistry department of a world leading university, and the chemists there were obsessed with NMR. They had small benchtop NMR machines. They had larger machines. They had a room full of huge machines. They had them in corridors and on desk tops. Chemists really love that stuff. More precisely, these are used for NMR spectroscopy, which helps identify what a sample is made of.

Introduction to NMR by Allery Chemistry

. Source. - only works with an odd number of nucleons

- apply strong magnetic field, this separates the energy of up and down spins. Most spins align with field.

- send radio waves into sample to make nucleons go to upper energy level. We can see that the energy difference is small since we are talking about radio waves, low frequency.

- when nucleon goes back down, it re-emits radio waves, and we detect that. TODO: how do we not get that confused with the input wave, which is presumably at the same frequency? It appears to send pulses, and then wait for the response.

How to Prepare and Run a NMR Sample by University of Bath (2017)

Source. This is a more direct howto, cool to see. Uses a Bruker Corporation 300. They have a robotic arm add-on. Shows spectrum on computer screen at the end. Shame no molecule identification after that!This video has the merit of showing real equipment usage, including sample preparation.

Says clearly that NMR is the most important way to identify organic compounds.

- youtu.be/uNM801B9Y84?t=41 lists some of the most common targets, including hydrogen and carbon-13

- youtu.be/uNM801B9Y84?t=124 ethanol example

- youtu.be/uNM801B9Y84?t=251 they use solvents where all protium is replaced by deuterium to not affect results. Genius.

- youtu.be/uNM801B9Y84?t=354 usually they do 16 radio wave pulses

Introductory NMR & MRI: Video 01 by Magritek (2009)

Source. Precession and Resonance. Precession has a natural frequency for any angle of the wheel.Introductory NMR & MRI: Video 02 by Magritek (2009)

Source. The influence of temperature on spin statistics. At 300K, the number of up and down spins are very similar. As you reduce temperature, we get more and more on lower energy state.Introductory NMR & MRI: Video 03 by Magritek (2009)

Source. The influence of temperature on spin statistics. At 300K, the number of up and down spins are very similar. As you reduce temperature, we get more and more on lower energy state.NMR spectroscopy visualized by ScienceSketch

. Source. 2020. Decent explanation with animation. Could go into a bit more numbers, but OK. Spin experiments Updated 2025-07-16

- Stern-Gerlach experiment

- fine structure split in energy levels

- anomalous Zeeman effect

- of a more statistical nature, but therefore also macroscopic and more dramatically observable:

- ferromagnetism

- Bose-Einstein statistics vs Fermi-Dirac statistics. A notable example is the difference in superfluid transition temperature between superfluid helium-3 and superfluid helium-4.