Representation theory of algebraic groups is a branch of mathematics that studies how algebraic groups can act on vector spaces through linear transformations. More specifically, it examines the ways in which algebraic groups can be represented as groups of matrices, and how these representations can be understood and classified. ### Key Concepts: 1. **Algebraic Groups**: These are groups that have a structure of algebraic varieties.

Lang's theorem is a result in the field of algebraic geometry, specifically related to the properties of algebraic curves. It is named after the mathematician Serge Lang. The theorem primarily concerns algebraic curves and their points over various fields, specifically in the context of rational points and rational functions. One important version of Lang's theorem states that a smooth projective curve over a number field has only finitely many rational points unless the curve is of genus zero.

Borel–de Siebenthal theory is a mathematical framework primarily associated with the study of compact Lie groups and their representations, particularly in the context of algebraic groups and symmetric spaces. The theory deals with the classification of maximal connected solvable subgroups, or Borel subgroups, in the context of semisimple Lie groups. It extends concepts of Borel subgroups from the language of algebraic groups to that of Lie groups.

The Kempf vanishing theorem is a result in algebraic geometry that deals with the behavior of sections of certain vector bundles on algebraic varieties, particularly in the context of ample line bundles. Named after G. R. Kempf, the theorem addresses the vanishing of global sections of certain sheaves associated with a variety.

BCK algebra is a type of algebraic structure that is derived from the theory of logic and set theory. Specifically, it is a variant of binary operations that generalizes certain properties of Boolean algebras. The term "BCK" comes from the properties of the operations defined within the structure.

An empty semigroup is a mathematical structure that consists of an empty set equipped with a binary operation that is associative. A semigroup is defined as a set accompanied by a binary operation that satisfies two conditions: 1. **Associativity:** For any elements \( a, b, c \) in the semigroup, the equation \( (a * b) * c = a * (b * c) \) holds, where \( * \) is the binary operation.

A Pisot–Vijayaraghavan (PV) number is a type of algebraic number that is a real root of a monic polynomial with integer coefficients, where this root is greater than 1, and all other roots of the polynomial, which can be real or complex, lie inside the unit circle in the complex plane (i.e., have an absolute value less than 1).

Coalgebras are a mathematical concept primarily used in the fields of category theory and theoretical computer science. They generalize the notion of algebras, which are structures used to study systems with operations, to structures that focus on state-based systems and behaviors. ### Basic Definition: A **coalgebra** for a functor \( F \) consists of a set (or space) \( C \) equipped with a structure map \( \gamma: C \to F(C) \).

The term "J-structure" can refer to different concepts depending on the context in which it is used. Here are a few possible interpretations: 1. **Mathematics and Geometry**: In the context of mathematics, particularly in algebraic topology or manifold theory, J-structure can refer to a specific type of geometric or topological structure associated with a mathematical object. It might relate to an almost complex structure or a similar concept depending on the area of study.

Algebraic structures are fundamental concepts in abstract algebra, a branch of mathematics that studies algebraic systems in a broad manner. Here’s an outline of key algebraic structures: ### 1. **Introduction to Algebraic Structures** - Definition and significance of algebraic structures in mathematics. - Examples of basic algebraic systems. ### 2. **Groups** - Definition of a group: A set equipped with a binary operation satisfying closure, associativity, identity, and invertibility.

The Grothendieck group is an important concept in abstract algebra, particularly in the areas of algebraic topology, algebraic geometry, and category theory. It is used to construct a group from a given commutative monoid, allowing the extension of operations and structures in a way that respects the original monoid's properties.

A double groupoid is a mathematical structure that generalizes the concept of a groupoid. To understand what a double groupoid is, it helps to first clarify what a groupoid is. ### Groupoid A **groupoid** consists of a set of objects and a set of morphisms (arrows) between these objects satisfying certain axioms. Specifically: - Each morphism has a source and target object.

In mathematics, the concept of **essential dimension** is a notion in algebraic geometry and representation theory, primarily related to the study of algebraic structures and their invariant properties under field extensions. It provides a way to quantify the "complexity" of objects, such as algebraic varieties or algebraic groups, in terms of the dimensions of the fields needed to define them.

A finitely generated abelian group is a specific type of group in abstract algebra that has some important properties. 1. **Group**: An abelian group is a set equipped with an operation (often called addition) that satisfies four properties: closure, associativity, identity, and inverses. Additionally, an abelian group is commutative, meaning that the order in which you combine elements does not matter (i.e.

In abstract algebra, a **semigroup** is a fundamental algebraic structure consisting of a set equipped with an associative binary operation. Formally, a semigroup is defined as follows: 1. **Set**: Let \( S \) be a non-empty set.

The term "Right Group" can refer to different organizations or movements depending on the context, such as political or ideological groups that advocate for conservative or right-leaning policies. However, it is not a widely recognized or specific organization without additional context. If you're referring to a particular group, organization, or movement (e.g.

Baddari Kamel is a traditional dish from the Middle East, particularly associated with Palestinian cuisine. It consists of lamb (or sometimes other meats) that is slow-cooked with vegetables and spices, typically served over rice. The dish is known for its rich flavors and fragrant spices, which can include ingredients like cumin, coriander, and cinnamon.

Pidgin code generally refers to a type of programming language that is designed to be simple, often using a limited set of vocabulary or commands to allow for easy communication between developers or with systems. However, the term “Pidgin” can also refer to a broader context, such as: 1. **Pidgin Languages**: In linguistics, a pidgin is a simplified language that develops as a means of communication between speakers of different native languages.

"Iota" and "Jot" are terms often used in different contexts, and their meanings can vary based on the subject matter. 1. **Iota**: - **Greek Alphabet**: In the Greek alphabet, Iota (Ι, ι) is the ninth letter. In the system of Greek numerals, it has a value of 10.

Structured English is a method of representing algorithms and processes in a clear and understandable way using a combination of plain English and specific syntactic constructs. It is often used in the fields of business analysis, systems design, and programming to communicate complex ideas in a simplified, readable format. The key objective of Structured English is to ensure that the logic and steps of a process are easily understood by people, including those who may not have a technical background.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

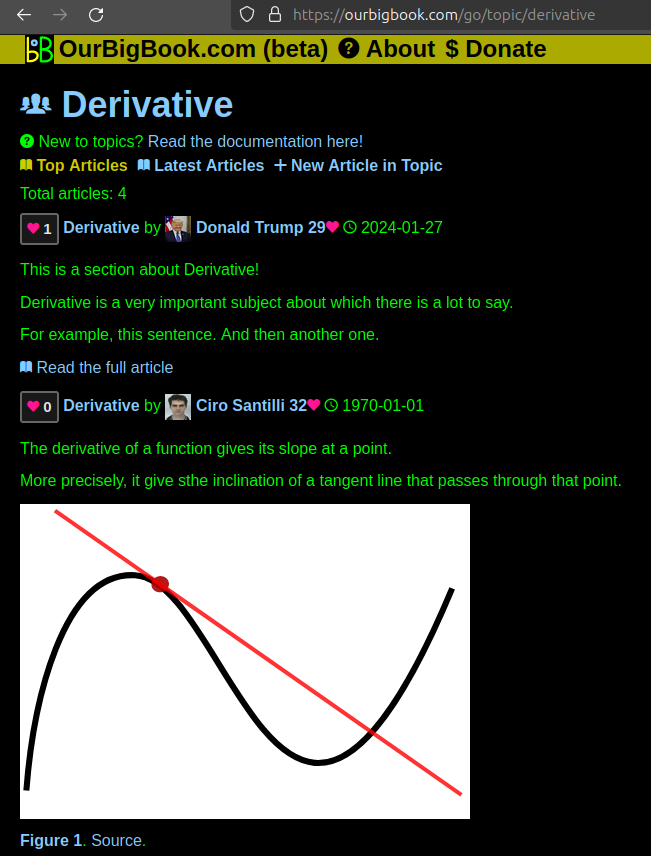

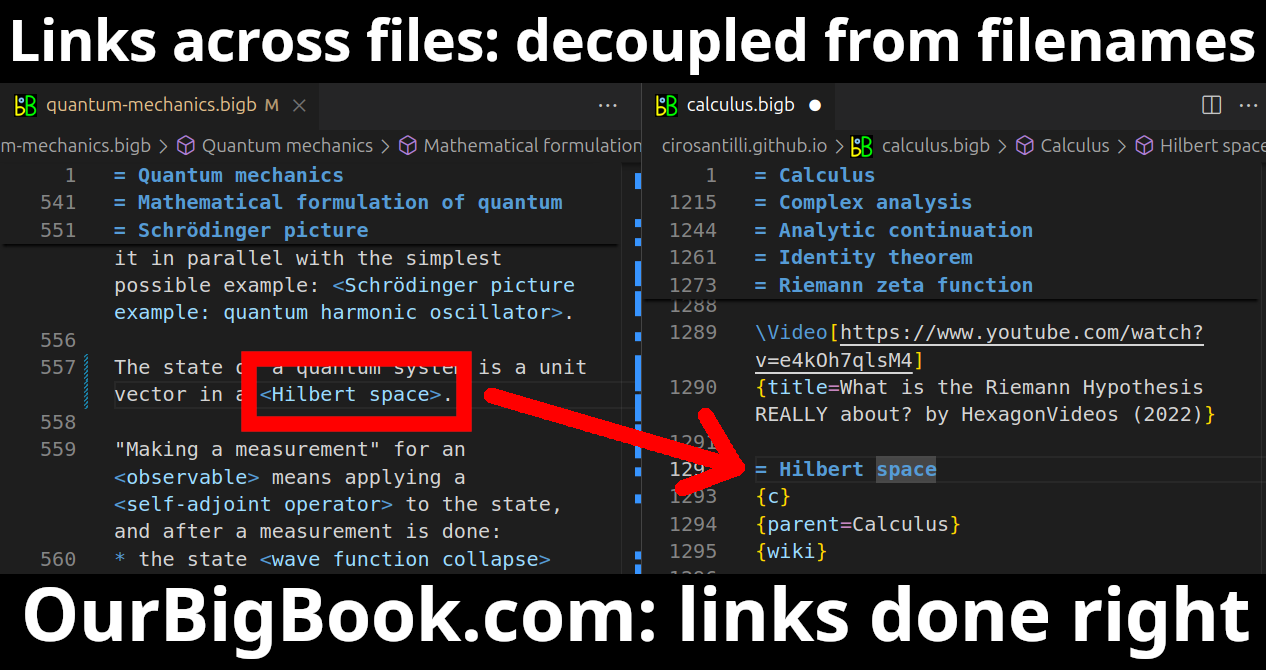

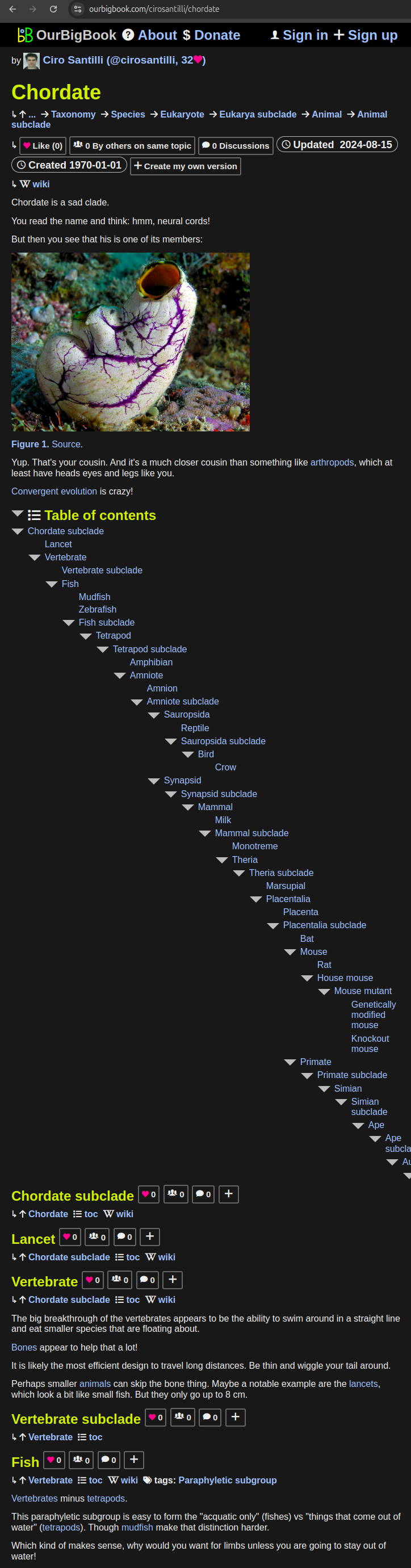

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

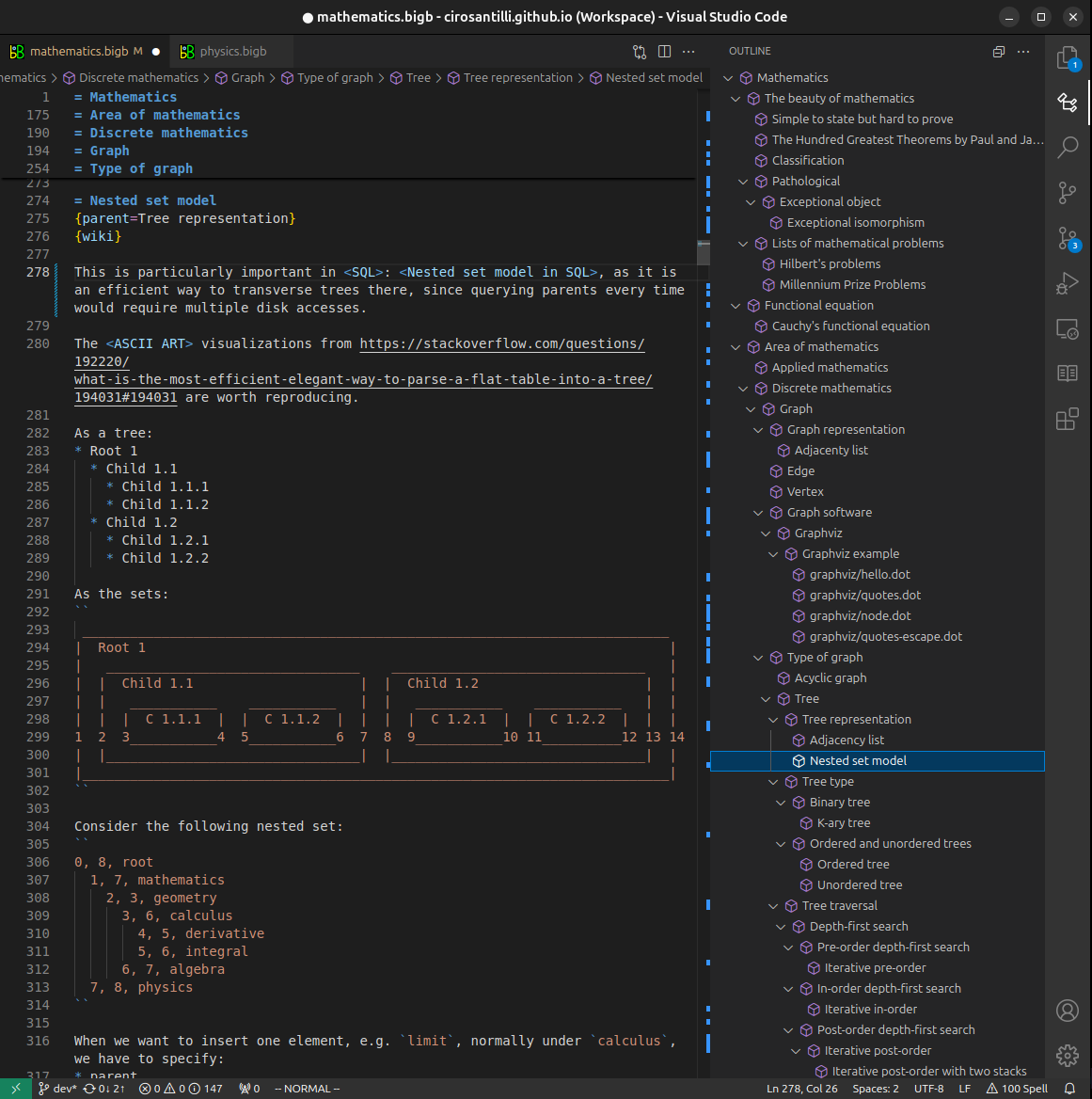

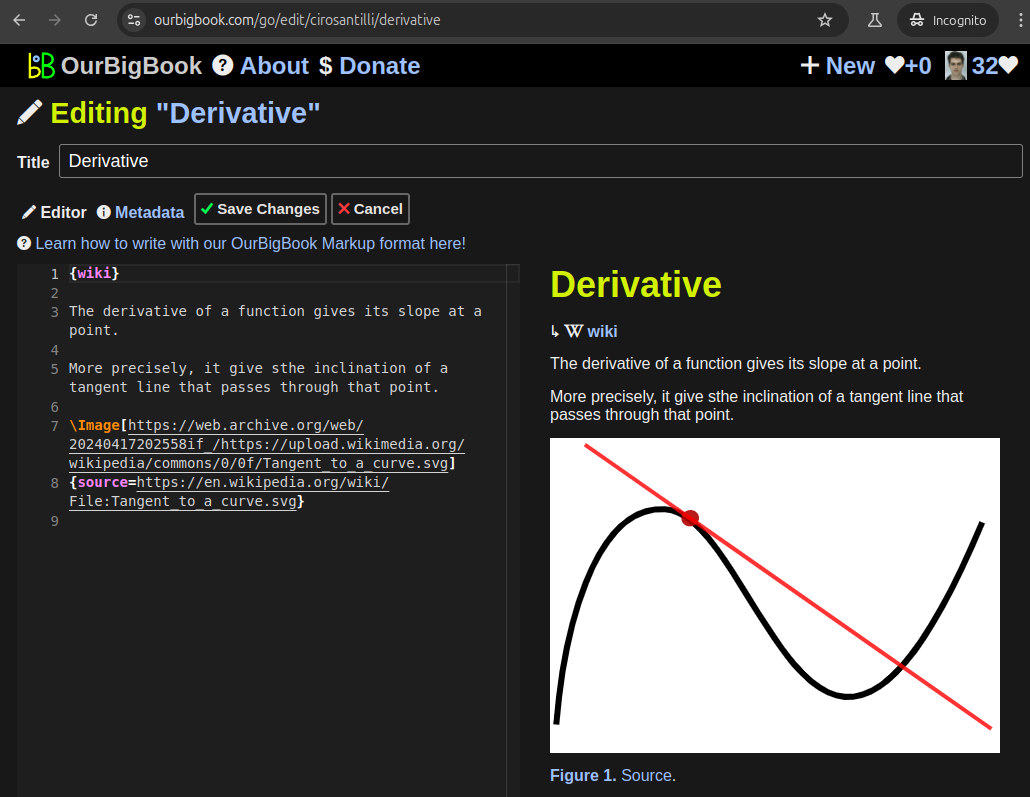

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact