John Perdew is a prominent physicist known for his contributions to the field of condensed matter physics, particularly in the area of density functional theory (DFT). He is a professor at Tulane University and has made significant advancements in the theoretical understanding of electronic structure and materials science. Perdew's work has helped to develop methods for predicting the properties of atoms, molecules, and solids with a computationally efficient approach.

John Radford Young is not widely recognized in popular culture or historical records, and it is possible that you may be referring to a specific individual not broadly known or documented.

The Johnson-Wilson theory is a theoretical framework used in solid-state physics and condensed matter physics to describe the electronic structure of materials, particularly correlated electron systems like high-temperature superconductors and heavy fermion compounds. This theory builds on concepts from quantum mechanics and many-body physics. The key aspects of Johnson-Wilson theory include: 1. **Effective Hamiltonian**: The theory often employs model Hamiltonians that capture the essential interactions and correlations between electrons in a material.

John Winthrop (1588–1649) was an English Puritan lawyer and a leading figure in the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. While he is primarily known as a political leader and governor, he also made contributions to education, particularly in the context of the Puritan emphasis on literacy and moral instruction.

Jon Speelman is a British chess player and author, recognized for his contributions to the game and his achievements in competitive play. He holds the title of International Master (IM) and has been active in chess for several decades. Speelman is notable for his analytical skills and has contributed to chess literature, writing articles and books that explore various aspects of chess strategy and tactics. He has also been involved in chess commentary and education.

As of my last knowledge update in October 2023, Jorge V. José is a recognized figure in the field of mathematics, particularly known for his contributions to mathematical biology, mathematical modeling, and differential equations. He has been involved in various research projects and has published numerous papers in scholarly journals. However, specific details about his work, career, or contributions might have evolved since then.

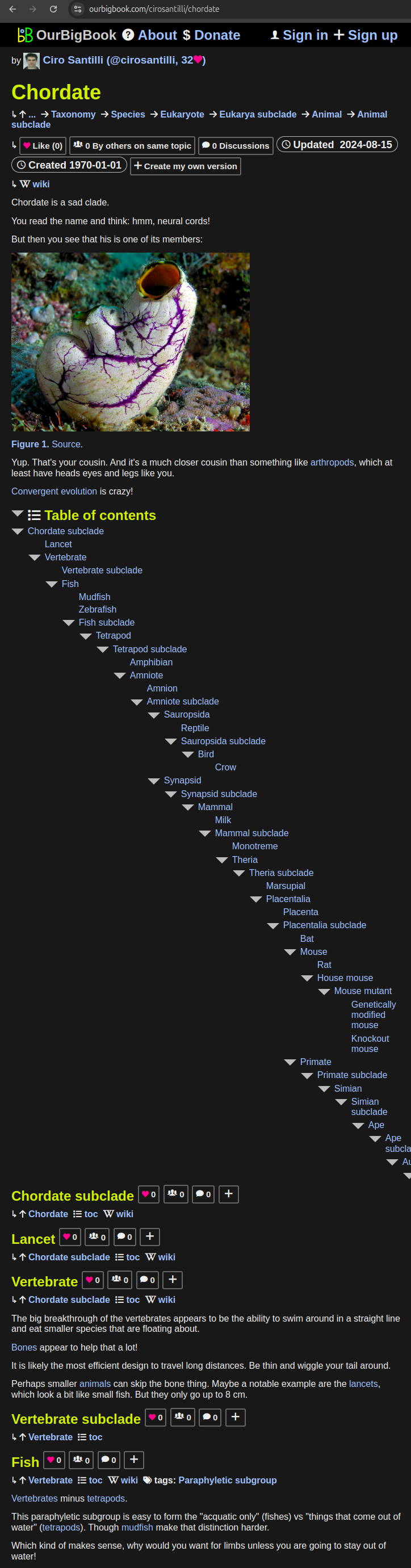

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

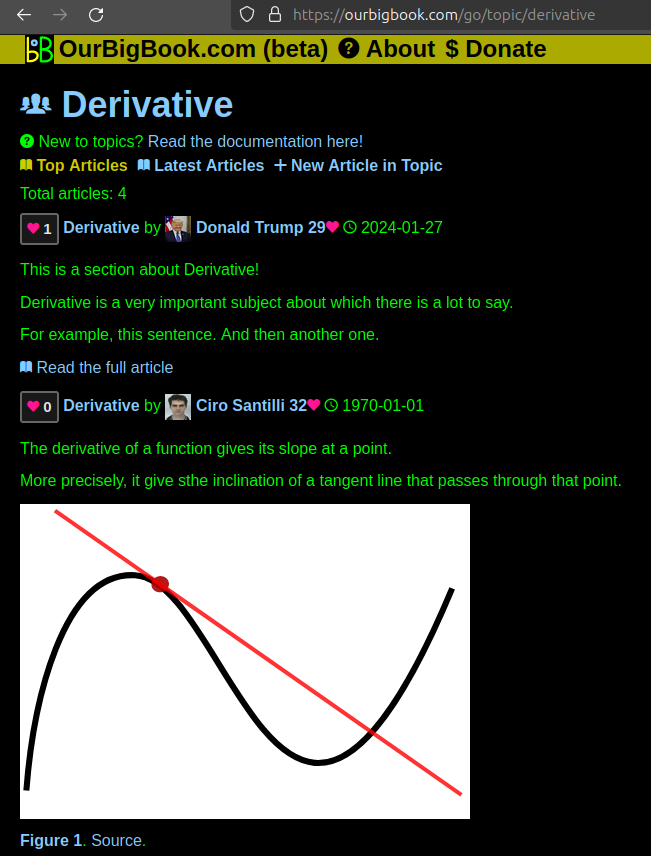

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

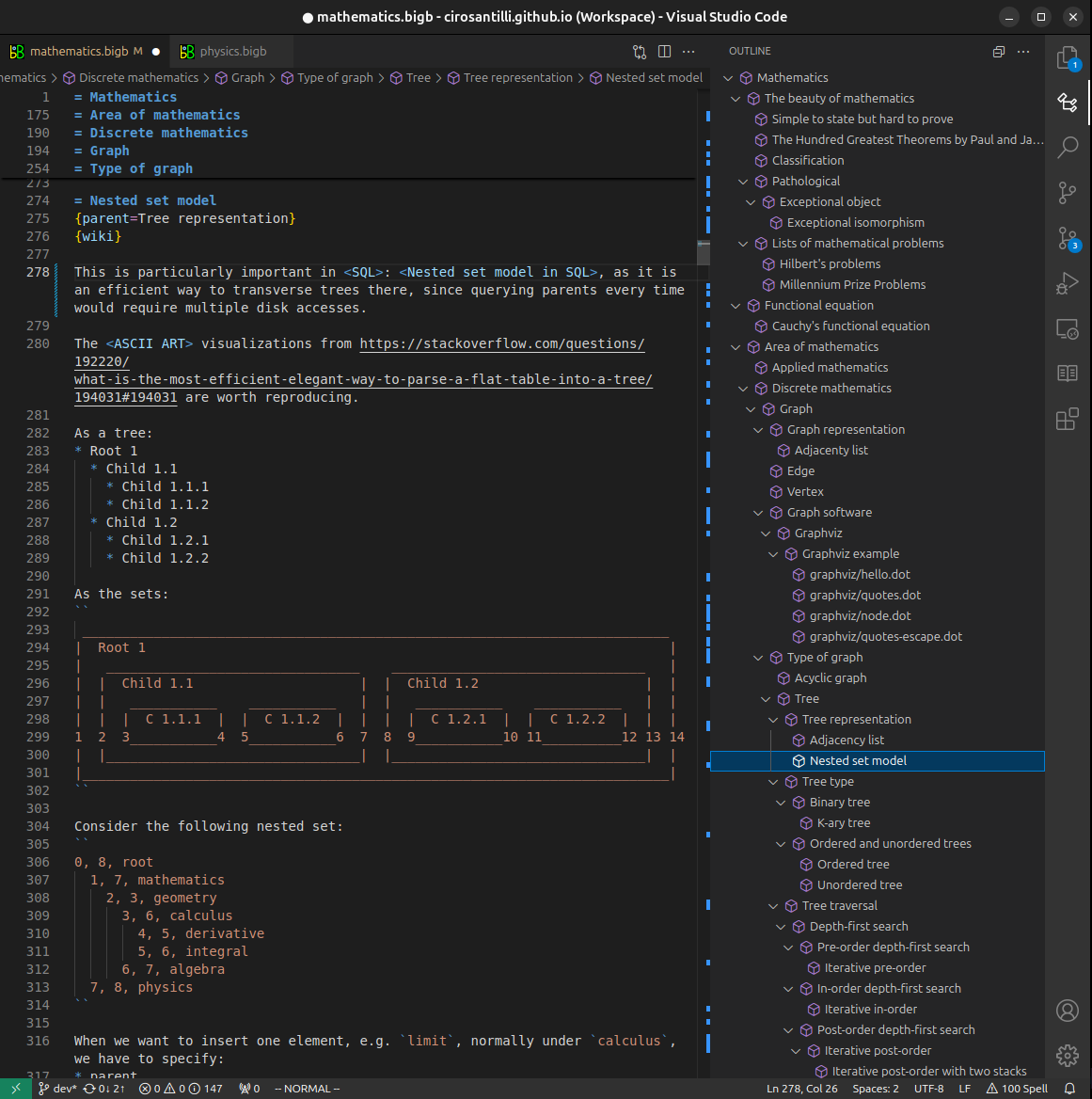

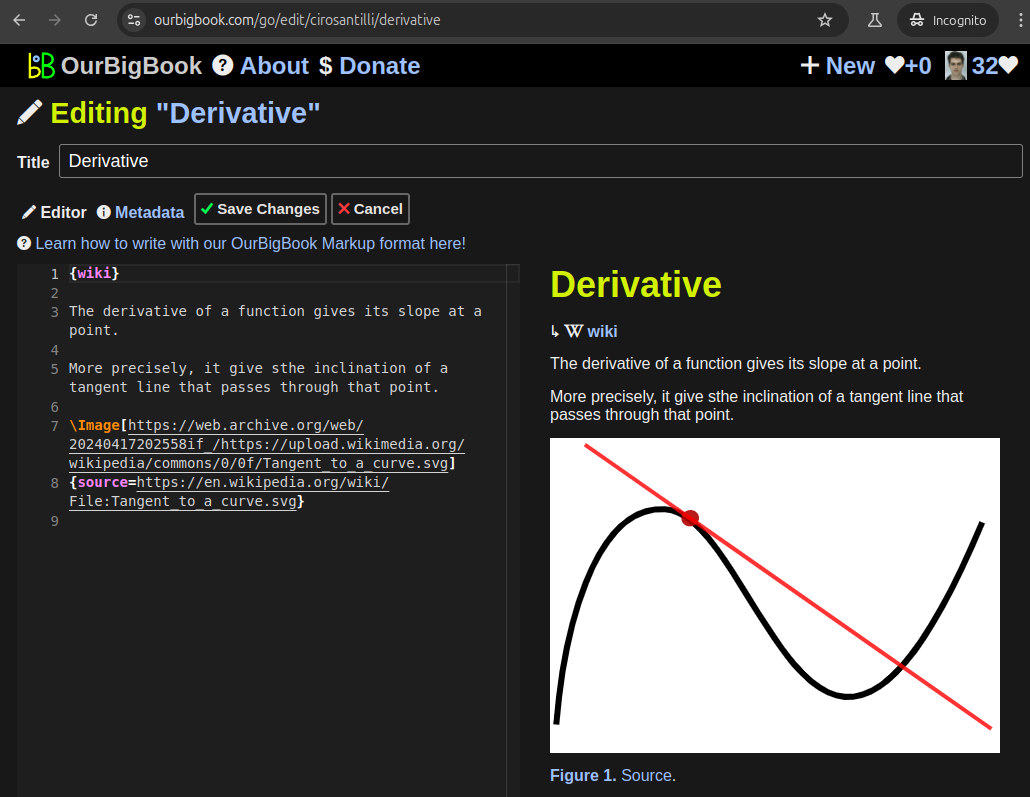

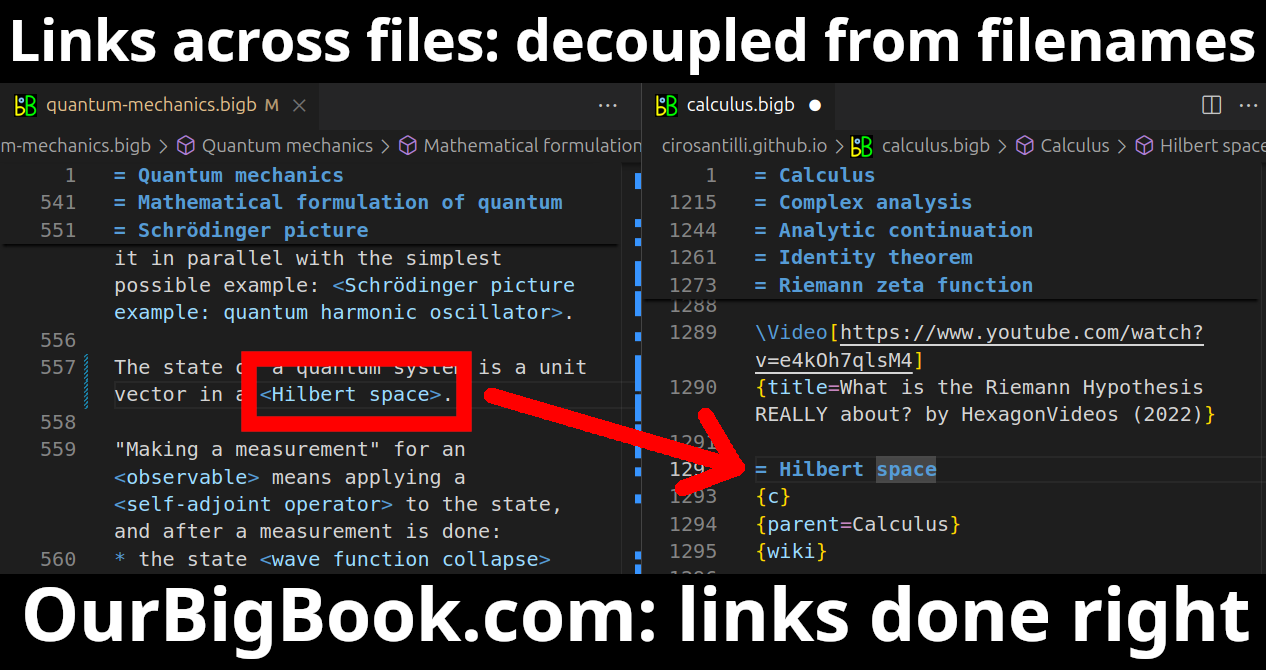

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact