Ciro Santilli's campaign for freedom of speech in China Updated 2025-07-16

Centerpiece: github.com/cirosantilli/china-dictatorship

Fully rendered at: github.com/china-dictatorship

The campaign has centered around publishing censored keywords on his Stack Overflow username, thus using his considerable Stack Overflow presence to sabotage the website in China. Here is an early web archive.

Chrysanthemum Xi Jinping with 六四 spice added by Ciro Santilli

. This was one of the profile pictures that Ciro Santilli used as part of his campaign.

Ciro later went on to prefer the "unmodified" Xi Jinping photo cover of some edition Xi Jinping Though, which also reminds Ciro very much of religious devotional pictures, e.g. those of Li Hongzhi.

Ciro understood that the best propaganda against a dictatorial enemy is recontextualized unmodified propaganda produced by the enemy itself. Their propaganda speaks for itself

Like most people in the West, Ciro has always been for political freedom of speech, and therefore against the Chinese government's policies.

However, the seriousness of the matter only fully dawned on him in 2015 when, his mother-in-law, a then a 63-year-old lady, was put into jail for 15 days for doing Falun Gong.

And all of this was made 100 times worse because Ciro deeply loves several aspects of China, such as food, language, art and culture, and saw it all being destroyed by the Communists: cirosantilli.com/china-dictatorship/does-ciro-santilli-hate-china

The rationale of this is to force the Chinese government to either:

- leave things as they are, and let censored keywords appear on Stack Overflow (most likely scenario)

- block Stack Overflow, and lose billions of dollars with worse IT technology

- disable the Great Firewall

In the beginning, this generated some commotion, but activity reduced as novelty wore off, and as he collected the reply to all possible comments at: github.com/cirosantilli/china-dictatorship.

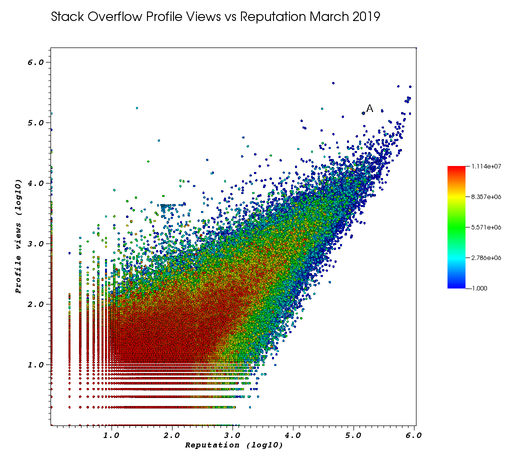

This campaign has led him to have an insane profile view/reputation ratio, since many people pause to look at his profile. He is point "A" at the top right corner of Figure 2. "Scatter plot of Stack Overflow user reputation vs profile views in March 2019 with Ciro Santilli marked as A":

Ciro feels that the view count started increasing more slowly since 2020 compared to his reputation, likely every single Chinese user has already viewed the profile.

Further analysis has been done at: stats.stackexchange.com/questions/376361/how-to-find-the-sample-points-that-have-statistically-meaningful-large-outlier-r

Ciro Santilli with a stone carved Budai in the Feilai Feng caves near the Lingyin Temple in Hangzhou taken during his legendary 2012 touristic trip to China

. Will he ever be able to go to China again to re-experience such marvelous locations?Water Margin tribute to Chinese dissidents by Ciro Santilli (2022)

Source. More information: cirosantilli.com/china-dictatorship/water-margin Cool data embedded in the Bitcoin blockchain Updated 2025-07-19

This is a collection of cool data found in the Bitcoin blockchain using techniques mentioned at: Section "How to extract data from the Bitcoin blockchain". Notably, Ciro Santilli developed his own set of scripts at github.com/cirosantilli/bitcoin-inscription-indexer to find some of this data. This article is based on data analyzed up to around block 831k (February 2024).

Drop some Bitcoins at 3KRk7f2JgekF6x7QBqPHdZ3pPDuMdY3eWR if you are loaded and like this article in order to support some much needed higher educational reform: Section "Sponsor Ciro Santilli's work on OurBigBook.com".

When this kind of non-financial data is embedded into a blockchain some people called an "inscription". The study or "early" inscriptions had been called a form of "archaeology"[ref][ref]. Since this is a collection of archeological artifacts, we call it a "museum"!

My Bitcoin inscription museum by Ciro Santilli

. Source. Introductory video to this article. Edited from Aratu Week 2024 Talk by Ciro Santilli: My Best Random Projects.One really cool thing about inscriptions is that because blockchains are huge Merkle trees, it is impossible to censor any one inscription without censoring the entire blockchain. It is also really cool to see people treating the Bitcoin blockchain basically like a global social media feed!

Starting on December 2022, ordinal ruleset inscriptions took the bitcoin blockchain by storm, and dwarfed in volume all other previous inscriptions. This museum focuses mostly on non-ordinals, though certain specific ordinal topics that especially interest he curators may be covered, e.g. Ordinal ruleset inscription porn and ordinal ASCII art inscription.

Hidden surprises in the Bitcoin blockchain by Ken Shirriff (2014) is a mandatory precursor to this article and contains the most interesting examples of the time. But much happened since Ken's article which we try to cover. This analysis is also a bit more data oriented through our usage of scripting.

Artifacts can be organized in various ways:In this article we've done a mixture of:

- chronologically

- by media type, e.g. images vs text

- by themes or events, e.g. the Prayer wars or Mt. Gox' shutdown

- encoding, e.g. AtomSea & EMBII vs raw images

Who said it was easy to be a museum curator!

E. Coli Whole Cell Model by Covert Lab Updated 2025-07-16

github.com/CovertLab/WholeCellEcoliRelease is a whole cell simulation model created by Covert Lab and other collaborators.

The project is written in Python, hurray!

But according to te README, it seems to be the use a code drop model with on-request access to master. Ciro Santilli asked at rationale on GitHub discussion, and they confirmed as expected that it is to:

- to prevent their publication ideas from being stolen. Who would steal publication ideas with public proof in an issue tracker without crediting original authors? Academia is broken. Academia should be the most open form of knowledge sharing. But instead we get this silly competition for publication points.

- to prevent noise from non-collaborators. But they only get like 2 issues as year on such a meganiche subject... Did you know that you can ignore people, and even block them if they are particularly annoying? Much more likely is that no one will every hear about your project and that it will die with its last graduate student slave.

The project is a followup to the earlier M. genitalium whole cell model by Covert lab which modelled Mycoplasma genitalium. E. Coli has 8x more genes (500 vs 4k), but it the undisputed bacterial model organism and as such has been studied much more thoroughly. It also reproduces faster than Mycoplasma (20 minutes vs a few hours), which is a huge advantages for validation/exploratory experiments.

The project has a partial dependency on the proprietary optimization software CPLEX which is freeware, for students, not sure what it is used for exactly, from the comment in the

requirements.txt the dependency is only partial.This project makes Ciro Santilli think of the E. Coli as an optimization problem. Given such external nutrient/temperature condition, which DNA sequence makes the cell grow the fastest? Balancing metabolites feels like designing a Factorio speedrun.

There is one major thing missing thing in the current model: promoters/transcription factor interactions are not modelled due to lack/low quality of experimental data: github.com/CovertLab/WholeCellEcoliRelease/issues/21. They just have a magic direct "transcription factor to gene" relationship, encoded at reconstruction/ecoli/flat/foldChanges.tsv in terms of type "if this is present, such protein is expressed 10x more". Transcription units are not implemented at all it appears.

Everything in this section refers to version 7e4cc9e57de76752df0f4e32eca95fb653ea64e4, the code drop from November 2020, and was tested on Ubuntu 21.04 with a docker install of

docker.pkg.github.com/covertlab/wholecellecolirelease/wcm-full with image id 502c3e604265, unless otherwise noted. ELF Hello World Tutorial Updated 2025-07-16

Extracted from this Stack Overflow answer.

How to use an Oxford Nanopore MinION to extract DNA from river water and determine which bacteria live in it Updated 2025-07-16

This article gives an idea of how this kind of biological experiment feels like to a software engineer who has never done any biology like Ciro Santilli.

Programmer's model of quantum computers Updated 2025-07-16

This is a quick tutorial on how a quantum computer programmer thinks about how a quantum computer works. If you know:a concrete and precise hello world operation can be understood in 30 minutes.

- what a complex number is

- how to do matrix multiplication

- what is a probability

Although there are several types of quantum computer under development, there exists a single high level model that represents what most of those computers can do, and we are going to explain that model here. This model is the is the digital quantum computer model, which uses a quantum circuit, that is made up of many quantum gates.

Beyond that basic model, programmers only may have to consider the imperfections of their hardware, but the starting point will almost always be this basic model, and tooling that automates mapping the high level model to real hardware considering those imperfections (i.e. quantum compilers) is already getting better and better.

The way quantum programmers think about a quantum computer in order to program can be described as follows:

- the input of a N qubit quantum computer is a vector of dimension N containing classic bits 0 and 1

- the quantum program, also known as circuit, is a unitary matrix of complex numbers that operates on the input to generate the output

- the output of a N qubit computer is also a vector of dimension N containing classic bits 0 and 1

Each time you do this, you are literally conducting a physical experiment of the specific physical implementation of the computer:and each run as the above can is simply called "an experiment" or "a measurement".

- setup your physical system to represent the classical 0/1 inputs

- let the state evolve for long enough

- measure the classical output back out

The output comes out "instantly" in the sense that it is physically impossible to observe any intermediate state of the system, i.e. there are no clocks like in classical computers, further discussion at: quantum circuits vs classical circuits. Setting up, running the experiment and taking the does take some time however, and this is important because you have to run the same experiment multiple times because results are probabilistic as mentioned below.

But the each output is not equally likely either, otherwise the computer would be useless except as random number generator!

This is because the probabilities of each output for a given input depends on the program (unitary matrix) it went through.

Therefore, what we have to do is to design the quantum circuit in a way that the right or better answers will come out more likely than the bad answers.

We then calculate the error bound for our circuit based on its design, and then determine how many times we have to run the experiment to reach the desired accuracy.

The probability of each output of a quantum computer is derived from the input and the circuit as follows.

First we take the classic input vector of dimension N of 0's and 1's and convert it to a "quantum state vector" of dimension :

We are after all going to multiply it by the program matrix, as you would expect, and that has dimension !

Note that this initial transformation also transforms the discrete zeroes and ones into complex numbers.

For example, in a 3 qubit computer, the quantum state vector has dimension and the following shows all 8 possible conversions from the classic input to the quantum state vector:

000 -> 1000 0000 == (1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

001 -> 0100 0000 == (0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

010 -> 0010 0000 == (0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

011 -> 0001 0000 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

100 -> 0000 1000 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0)

101 -> 0000 0100 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0, 0.0)

110 -> 0000 0010 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0, 0.0)

111 -> 0000 0001 == (0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 0.0, 1.0)This can be intuitively interpreted as:

- Therefore, the probability of all three 0's is 1.0, and all other possible combinations have 0 probability.

- if the classic input is

001, then we are certain that bit one and two are 0, and bit three is 1. The probability of that is 1.0, and all others are zero. - and so on

Now that we finally have our quantum state vector, we just multiply it by the unitary matrix of the quantum circuit, and obtain the dimensional output quantum state vector :

And at long last, the probability of each classical outcome of the measurement is proportional to the square of the length of each entry in the quantum vector, analogously to what is done in the Schrödinger equation.

Then, the probability of each possible outcomes would be the length of each component squared:i.e. 75% for the first, and 25% for the third outcomes, where just like for the input:

Keep in mind that the quantum state vector can also contain complex numbers because we are doing quantum mechanics, but we just take their magnitude in that case, e.g. the following quantum state would lead to the same probabilities as the previous one:

This interpretation of the quantum state vector clarifies a few things:

- the input quantum state is just a simple state where we are certain of the value of each classic input bit

- This is true for the input matrix, and unitary matrices have the probability of maintaining that property after multiplication.Unitary matrices are a bit analogous to self-adjoint operators in general quantum mechanics (self-adjoint in finite dimensions implies is stronger)This also allows us to understand intuitively why quantum computers may be capable of accelerating certain algorithms exponentially: that is because the quantum computer is able to quickly do an unitary matrix multiplication of a humongous sized matrix.If we are able to encode our algorithm in that matrix multiplication, considering the probabilistic interpretation of the output, then we stand a chance of getting that speedup.

As we could see, this model is was simple to understand, being only marginally more complex than that of a classical computer, see also: quantumcomputing.stackexchange.com/questions/6639/is-my-background-sufficient-to-start-quantum-computing/14317#14317 The situation of quantum computers today in the 2020's is somewhat analogous to that of the early days of classical circuits and computers in the 1950's and 1960's, before CPU came along and software ate the world. Even though the exact physics of a classical computer might be hard to understand and vary across different types of integrated circuits, those early hardware pioneers (and to this day modern CPU designers), can usefully view circuits from a higher level point of view, thinking only about concepts such as:as modelled at the register transfer level, and only in a separate compilation step translated into actual chips. This high level understanding of how a classical computer works is what we can call "the programmer's model of a classical computer". So we are now going to describe the quantum analogue of it.

- logic gates like AND, NOR and NOT

- a clock + registers

Bibliography:

- arxiv.org/pdf/1804.03719.pdf Quantum Algorithm Implementations for Beginners by Abhijith et al. 2020

Uranium vs plutonium Quora answer by Ciro Santilli Updated 2025-07-16

x86 Paging Tutorial Updated 2025-07-19

This tutorial explains the very basics of how paging works, with focus on x86, although most high level concepts will also apply to other instruction set architectures, e.g. ARM.

The goals are to:

This tutorial was extracted and expanded from this Stack Overflow answer.