Why do multiple electrons occupy the same orbital if electrons repel each other? by  Ciro Santilli 37 Updated 2025-07-16

Ciro Santilli 37 Updated 2025-07-16

As shown at Schrödinger equation solution for the helium atom, they do repel each other, and that affects their measurable energy.

This changes however at higher orbitals, notably as approximately described by the aufbau principle.

Boring rule that says that less energetic atomic orbitals are filled first.

Much more interesting is actually determining that order, which the Madelung energy ordering rule is a reasonable approximation to.

TODO motivation. Motivation. Motivation. Motivation. The definitin with quotient group is easy to understand.

This notation is so confusing! People often don't manage to explain the intuition behind it, why this is an useful notation. When you see Indian university entry exam level memorization classes about this, it makes you want to cry.

The key reason why term symbols matter are Hund's rules, which allow us to predict with some accuracy which electron configurations of those states has more energy than the other.

web.chem.ucsb.edu/~devries/chem218/Term%20symbols.pdf puts it well: electron configuration notation is not specific enough, as each such notation e.g. 1s2 2s2 2p2 contains several options of spins and z angular momentum. And those affect energy.

This is why those symbols are often used when talking about energy differences: they specify more precisely which levels you are talking about.

Basically, each term symbol appears to represent a group of possible electron configurations with a given quantum angular momentum.

We first fix the energy level by saying at which orbital each electron can be (hyperfine structure is ignored). It doesn't even have to be the ground state: we can make some electrons excited at will.

The best thing to learn this is likely to draw out all the possible configurations explicitly, and then understand what is the term symbol for each possible configuration, see e.g. term symbols for carbon ground state.

It also confusing how uppercase letters S, P and D are used, when they do not refer to orbitals s, p and d, but rather to states which have the same angular momentum as individual electrons in those states.

It is also very confusing how extremelly close it looks to spectroscopic notation!

The form of the term symbol is:

Atomic Term Symbols by TMP Chem (2015)

Source. Atomic Term Symbols by T. Daniel Crawford (2016)

Source. Bibliography:

- chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry_Textbook_Maps/Supplemental_Modules_(Physical_and_Theoretical_Chemistry)/Spectroscopy/Electronic_Spectroscopy/Spin-orbit_Coupling/Atomic_Term_Symbols

- chem.libretexts.org/Courses/Pacific_Union_College/Quantum_Chemistry/08%3A_Multielectron_Atoms/8.08%3A_Term_Symbols_Gives_a_Detailed_Description_of_an_Electron_Configuration The PDF origin: web.chem.ucsb.edu/~devries/chem218/Term%20symbols.pdf

- chem.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Inorganic_Chemistry/Inorganic_Coordination_Chemistry_(Landskron)/08%3A_Coordination_Chemistry_III_-_Electronic_Spectra/8.01%3A_Quantum_Numbers_of_Multielectron_Atoms

- physics.stackexchange.com/questions/8567/how-do-electron-configuration-microstates-map-to-term-symbols How do electron configuration microstates map to term symbols?

Allow us to determine with good approximation in a multi-electron atom which electron configuration have more energy. It is a bit like the Aufbau principle, but at a finer resolution.

Note that this is not trivial since there is no explicit solution to the Schrödinger equation for multi-electron atoms like there is for hydrogen.

For example, consider carbon which has electron configuration 1s2 2s2 2p2.

Carbon has electronic structure 1s2 2s2 2p2.

For term symbols we only care about unfilled layers, because in every filled layer the total z angular momentum is 0, as one electron necessarily cancels out each other:

- magnetic quantum number varies from -l to +l, each with z angular momentum to and so each cancels the other out

- spin quantum number is either + or minus half, and so each pair of electron cancels the other out

So in this case, we only care about the 2 electrons in 2p2. Let's list out all possible ways in which the 2p2 electrons can be.

There are 3 p orbitals, with three different magnetic quantum numbers, each representing a different possible z quantum angular momentum.

We are going to distribute 2 electrons with 2 different spins across them. All the possible distributions that don't violate the Pauli exclusion principle are:

m_l +1 0 -1 m_L m_S

u_ u_ __ 1 1

u_ __ u_ 0 1

__ u_ u_ -1 1

d_ d_ __ 1 -1

d_ __ d_ 0 -1

__ d_ d_ -1 -1

u_ d_ __ 1 0

d_ u_ __ 1 0

u_ __ d_ 0 0

d_ __ u_ 0 0

__ u_ d_ -1 0

__ d_ u_ -1 0

ud __ __ 2 0

__ ud __ 0 0

__ __ ud -2 0where:

m_lis , the magnetic quantum number of each electron. Remember that this gives a orbital (non-spin) quantum angular momentum of to each such electronm_Lwith a capital L is the sum of the of each electronm_Swith a capital S is the sum of the spin angular momentum of each electron

For example, on the first line:we have:and so the sum of them has angular momentum . So the value of is 1, we just omit the .

m_l +1 0 -1 m_L m_S

u_ u_ __ 1 1- one electron with , and so angular momentum

- one electron with , and so angular momentum 0

TODO now I don't understand the logic behind the next steps... I understand how to mechanically do them, but what do they mean? Can you determine the term symbol for individual microstates at all? Or do you have to group them to get the answer? Since there are multiple choices in some steps, it appears that you can't assign a specific term symbol to an individual microstate. And it has something to do with the Slater determinant. The previous lecture mentions it: www.youtube.com/watch?v=7_8n1TS-8Y0 more precisely youtu.be/7_8n1TS-8Y0?t=2268 about carbon.

youtu.be/DAgEmLWpYjs?t=2675 mentions that is not allowed because it would imply , which would be a state

uu __ __ which violates the Pauli exclusion principle, and so was not listed on our list of 15 states.He then goes for and mentions:and so that corresponds to states on our list:Note that for some we had a two choices, so we just pick any one of them and tick them off off from the table, which now looks like:

ud __ __ 2 0

u_ d_ __ 1 0

u_ __ d_ 0 0

__ u_ d_ -1 0

__ __ ud -2 0 +1 0 -1 m_L m_S

u_ u_ __ 1 1

u_ __ u_ 0 1

__ u_ u_ -1 1

d_ d_ __ 1 -1

d_ __ d_ 0 -1

__ d_ d_ -1 -1

d_ u_ __ 1 0

d_ __ u_ 0 0

__ d_ u_ -1 0

__ ud __ 0 0Then for the choices are:so we have 9 possibilities for both together. We again verify that 9 such states are left matching those criteria, and tick them off, and so on.

Can we make any ab initio predictions about it all?

A 2016 paper: aip.scitation.org/doi/abs/10.1063/1.4948309

Isomers were quite confusing for early chemists, before atomic theory was widely accepted, and people where thinking mostly in terms of proportions of equations, related: Section "Isomers suggest that atoms exist".

A law of physics is Galilean invariant if the same formula works both when you are standing still on land, or when you are on a boat moving at constant velocity.

For example, if we were describing the movement of a point particle, the exact same formulas that predict the evolution of must also predict , even though of course both of those will have different values.

It would be extremely unsatisfactory if the formulas of the laws of physics did not obey Galilean invariance. Especially if you remember that Earth is travelling extremelly fast relative to the Sun. If there was no such invariance, that would mean for example that the laws of physics would be different in other planets that are moving at different speeds. That would be a strong sign that our laws of physics are not complete.

Lorentz invariance generalizes Galilean invariance to also account for special relativity, in which a more complicated invariant that also takes into account different times observed in different inertial frames of reference is also taken into account. But the fundamental desire for the Lorentz invariance of the laws of physics remains the same.

Logical consequence, often referred to in formal logic as entailment, is a relationship between statements whereby one statement (or set of statements) necessarily follows from another statement (or set of statements). In other words, if a set of premises logically entails a conclusion, then if the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. In more formal terms, we can express this using symbolic logic.

Example:

- the three most table polymorphs of calcium carbonate polymorphs are:

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

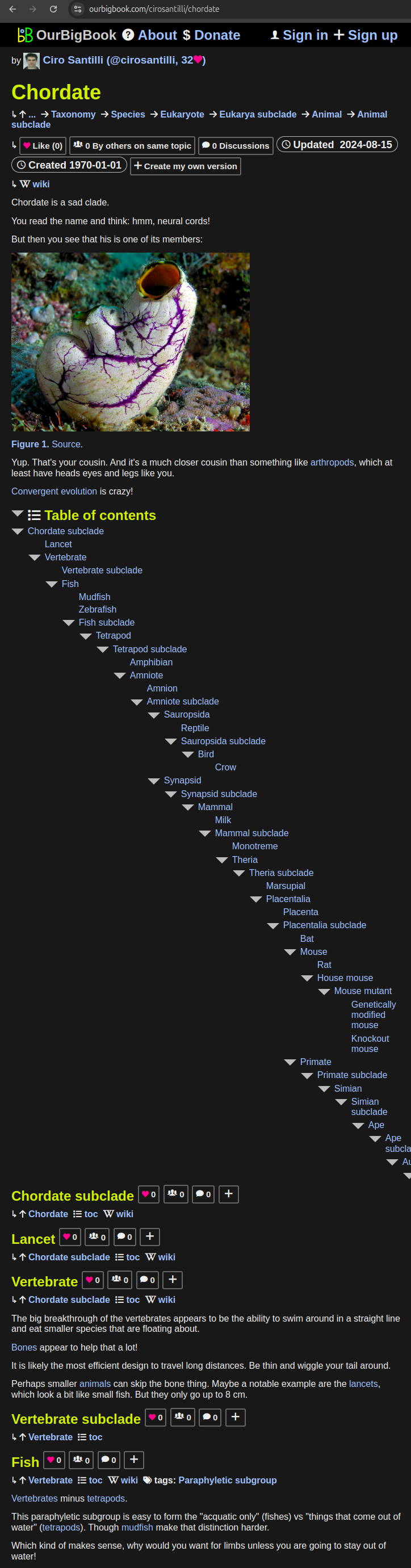

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

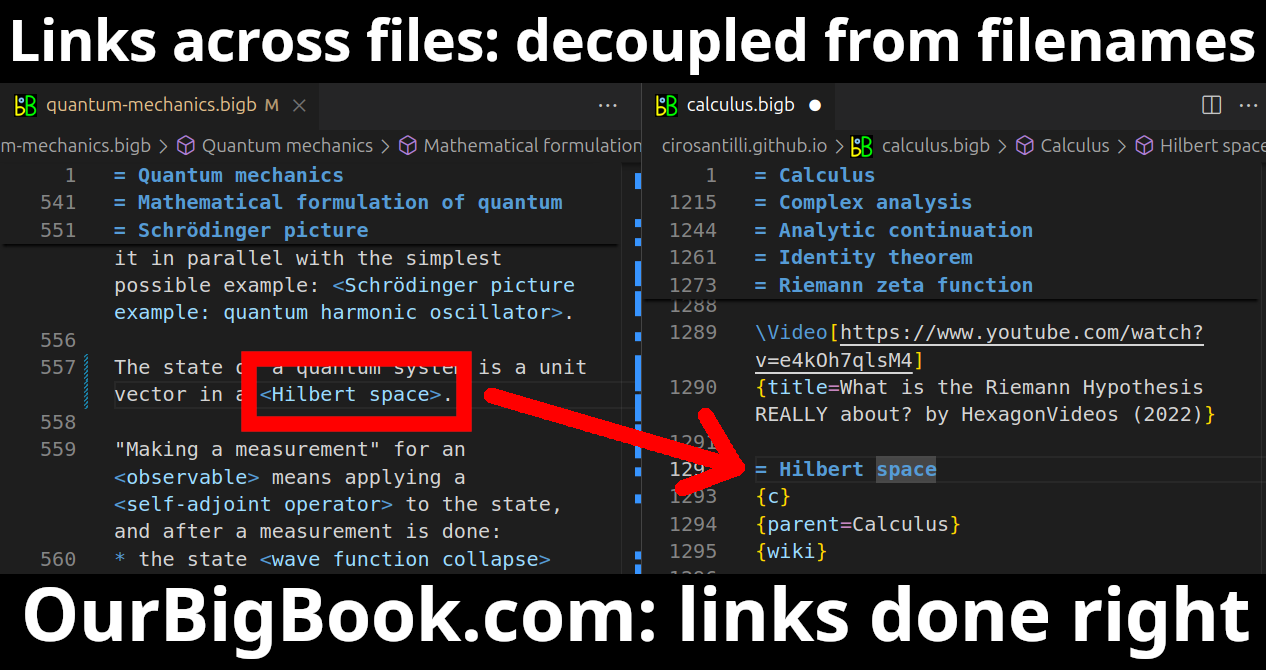

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

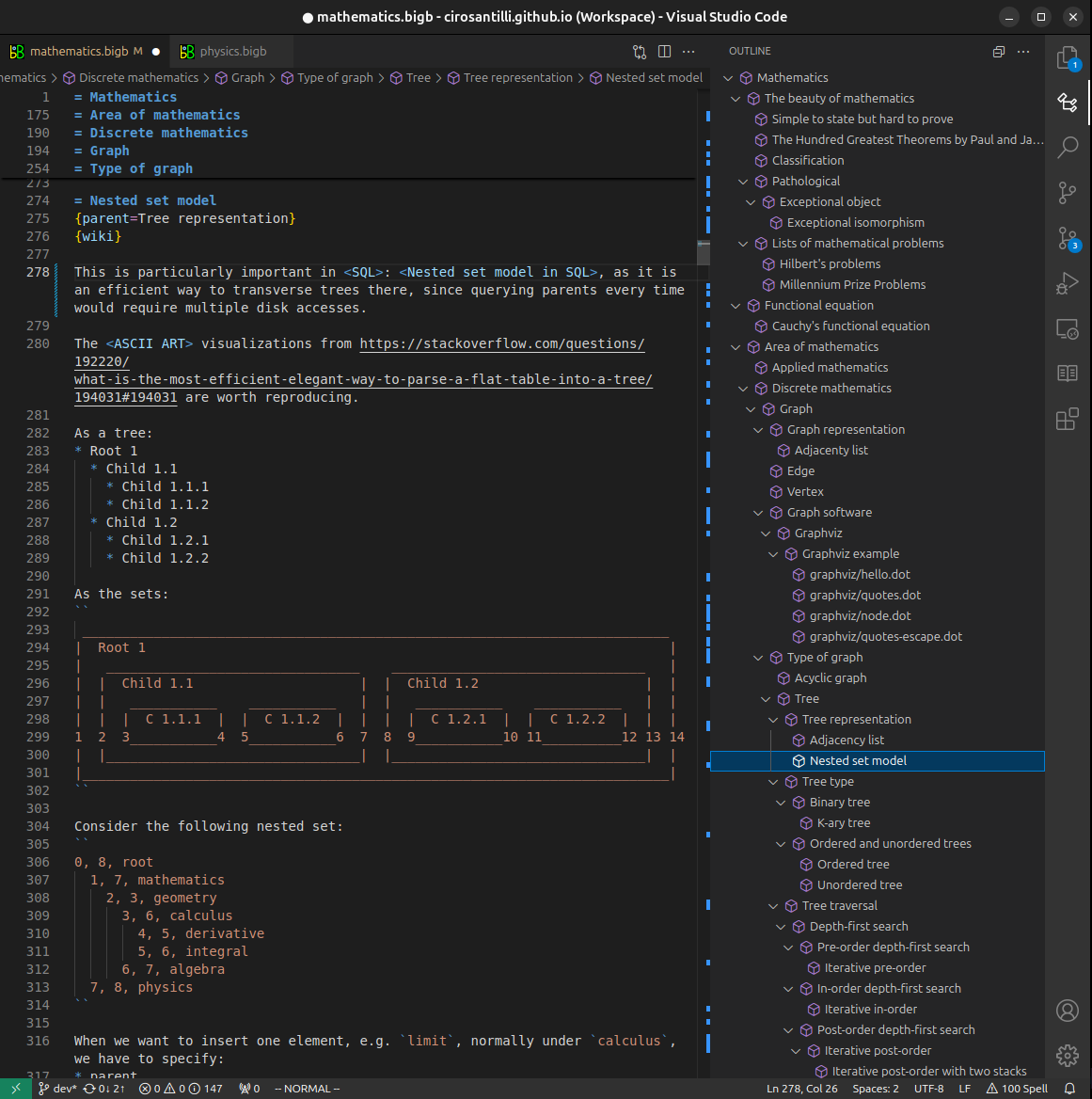

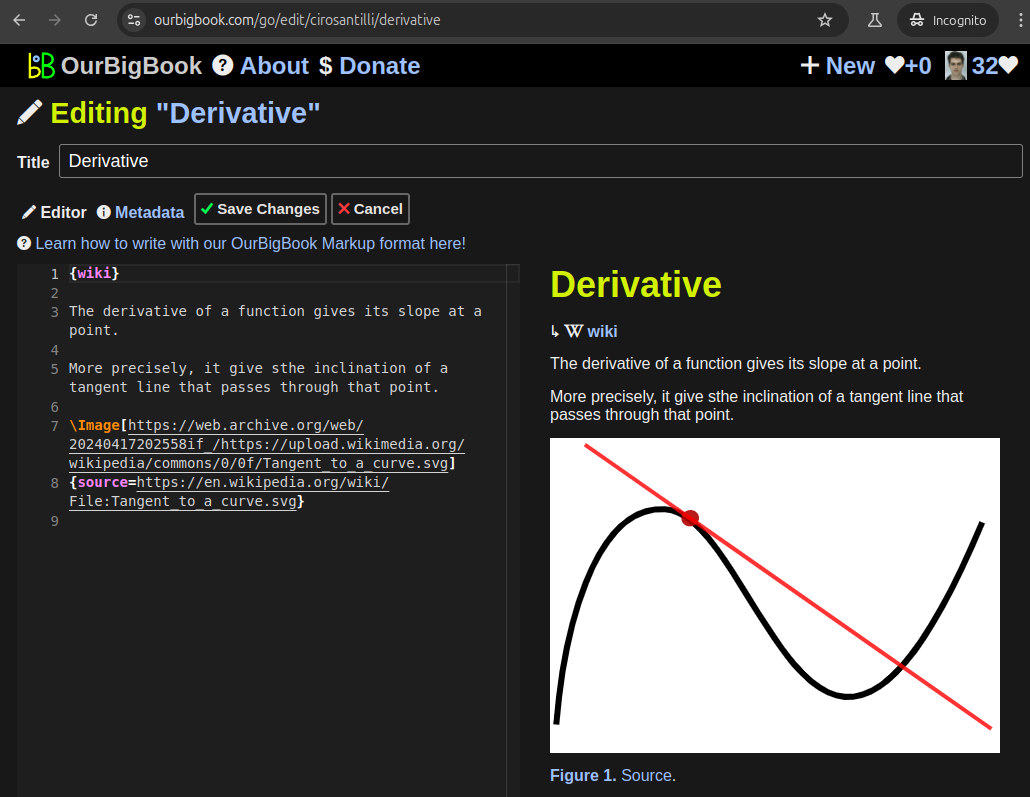

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact