A **service network** typically refers to a system of interconnected resources, such as people, technologies, and organizations, that collaborate to deliver services to customers or clients. These networks can vary widely depending on the context in which the term is used, but the following are some common characteristics and applications: 1. **Collaboration**: In a service network, different entities (e.g., businesses, service providers, or individuals) work together to provide a cohesive service offering.

"Waxwork" is a horror-comedy film released in 1988, directed by Anthony Hickox. The film follows a group of young friends who visit a mysterious wax museum, only to discover that the exhibits come to life and are connected to various horrifying stories and characters from horror history. As they explore the museum, they find themselves trapped in a nightmarish scenario where they must confront their worst fears and the deadly wax figures that inhabit the exhibits.

"A Mom for Christmas" is a family-oriented made-for-TV movie that was originally released in 1990. The film stars former child star Emma Roberts and features a heartwarming story about a young girl who wishes for her mother to be present for Christmas. In the film, a department store mannequin comes to life and becomes a mother figure to the girl, helping her navigate the challenges of the holiday season. The movie explores themes of love, family, and the magic of Christmas.

"Spasmo" can refer to a few different things depending on the context: 1. **Spasmo (film)**: "Spasmo" is an Italian giallo film released in 1974, directed by Umberto Lenzi. The film features a plot involving murder and psychological suspense, which is typical of the giallo genre known for its stylized violence, intricate plots, and mystery elements.

The Azoic hypothesis is a historical concept in geology and paleontology that posited that no life existed on Earth during the Precambrian era, which spans from the formation of the Earth around 4.6 billion years ago to the start of the Cambrian period about 541 million years ago. The term "azoic" means "without life.

Psychofagist is a musical project founded in 2001 by Italian musicians Francesco Ferdinandi and Marcello Rota. The project is known for its unique blend of various genres, including progressive rock, metal, and avant-garde music. Their sound is characterized by complex compositions, heavy guitar riffs, and experimental elements. The band's music often features a mix of instrumental pieces and vocal tracks, and they are recognized for their technical proficiency and innovative approach to songwriting.

Three-valued logic is a type of formal logic that extends classical binary logic (which uses only two truth values: true and false) by introducing a third truth value. The most common interpretation of this third value is "unknown" or "indeterminate," but the specific interpretation can vary depending on the context. In three-valued logic, the three truth values are often represented as: 1. **True (T)**: Represents objects that are true.

Marine biological stations are research facilities dedicated to the study of marine organisms, ecosystems, and the environmental processes that affect them. These stations are typically located near coastal areas, allowing for easy access to various marine habitats, such as oceans, estuaries, and coral reefs. They serve as bases for scientific research, education, and monitoring of marine environments.

SikTh is a British progressive metal band formed in 1999. Known for their complex musical style, SikTh incorporates various elements, including metalcore, avant-garde, and math rock. The band's music features intricate guitar work, unconventional song structures, and a blend of clean and harsh vocals. They gained a following for their innovative approach to metal, particularly noted for their use of dual vocalists and intricate rhythms.

Planktology is the scientific study of plankton, which includes a vast array of microscopic organisms that drift in the water column of oceans, seas, and other bodies of water. Plankton can be broadly classified into two main categories: phytoplankton, which are plant-like organisms (primarily algae that perform photosynthesis), and zooplankton, which are small animals, including protozoa and tiny crustaceans.

"A Naturalist in Indian Seas" is a notable work by the British naturalist and zoologist Alfred William Alcock, published in the early 20th century. The book details Alcock's extensive observations and research on the marine life of the Indian Ocean and surrounding waters. It includes descriptions of various marine species, insights into their habitats, behaviors, and the ecological dynamics of the region.

"War from a Harlot's Mouth" is a German metal band formed in 2005. Their music is characterized by a mix of metalcore, mathcore, and post-hardcore elements. The band's sound typically features aggressive vocals, complex guitar work, and intricate rhythms, which are hallmarks of the genres they draw from. The band's lyrical themes often explore personal struggles, social issues, and existential topics, set against a backdrop of intense and dynamic musical composition.

Aquatic feeding mechanisms refer to the various methods and adaptations that aquatic organisms use to capture, ingest, and process food. These mechanisms can vary widely based on the organism's environment, body structure, and dietary needs. Here are some common types of aquatic feeding mechanisms: 1. **Filter Feeding**: Many aquatic animals, such as bivalves (e.g., clams), sponges, and certain fish (e.g., basking sharks), use filter feeding.

The term "Belgian Scientific Expedition" typically refers to various scientific missions organized by Belgium, particularly during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, that aimed to explore and study different regions of the world. One of the most notable expeditions is the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897-1899, led by Adrien de Gerlache.

The European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODnet) is an initiative aimed at providing access to a wealth of marine data from various European sources. It was established to support the implementation of the European Union’s Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) and other related policies. EMODnet serves as a key component in enhancing marine knowledge and promoting the sustainable use of marine resources.

Intertidal ecology is the study of the ecosystems found in the intertidal zone, which is the area of the coastline that is exposed to air at low tide and submerged under water at high tide. This unique environment provides a diverse array of habitats and challenges due to fluctuating conditions such as temperature, salinity, moisture, and wave action. Key aspects of intertidal ecology include: 1. **Zonation**: The intertidal zone is often divided into different zones (e.

The Marine Station of Endoume, known in French as "Station Marine d'Endoume," is a marine research facility located in Marseille, France. It is part of the Mediterranean Institute of Oceanography (MIO) and is operated by the University of Aix-Marseille. The station is situated along the Mediterranean coast and serves as a center for marine research and environmental studies. The facility focuses on various aspects of marine science, including oceanography, marine biology, ecology, and conservation.

The Miami Science Barge is a unique educational facility and floating science museum located in Biscayne Bay, Miami, Florida. It serves as a platform for environmental education and sustainability, primarily focusing on topics related to marine science, ecology, and renewable energy. The barge features interactive exhibits, workshops, and hands-on learning experiences aimed at promoting awareness about the importance of science, conservation, and sustainable practices.

A pop-up satellite archival tag (PSAT) is a type of electronic device used by marine biologists and researchers to study the behavior, movement, and ecology of marine animals, particularly large species such as fish, seals, and turtles. These tags are designed to be attached to the animal for a certain period of time.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

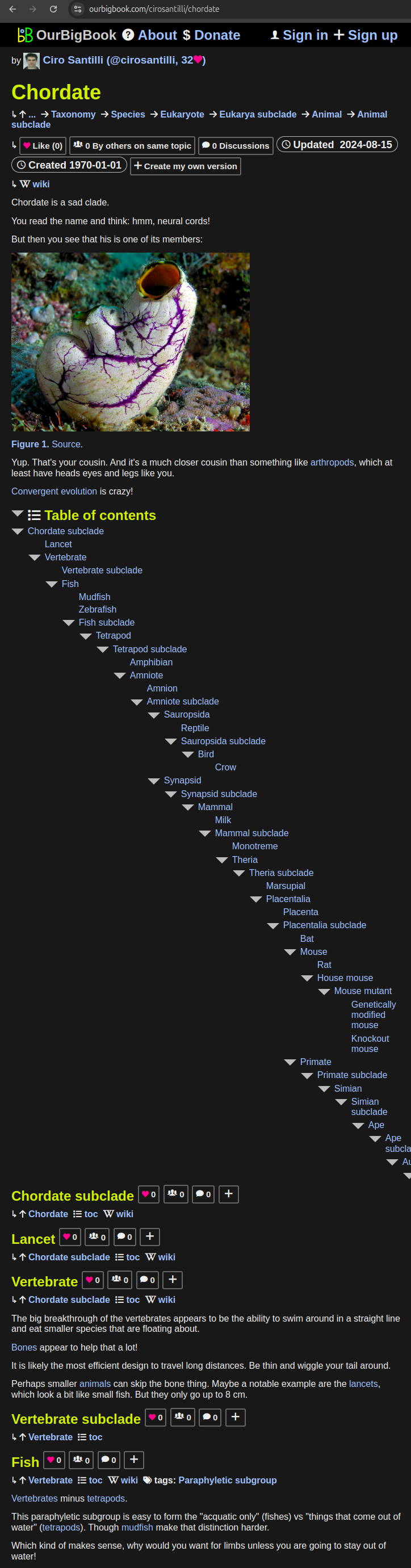

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

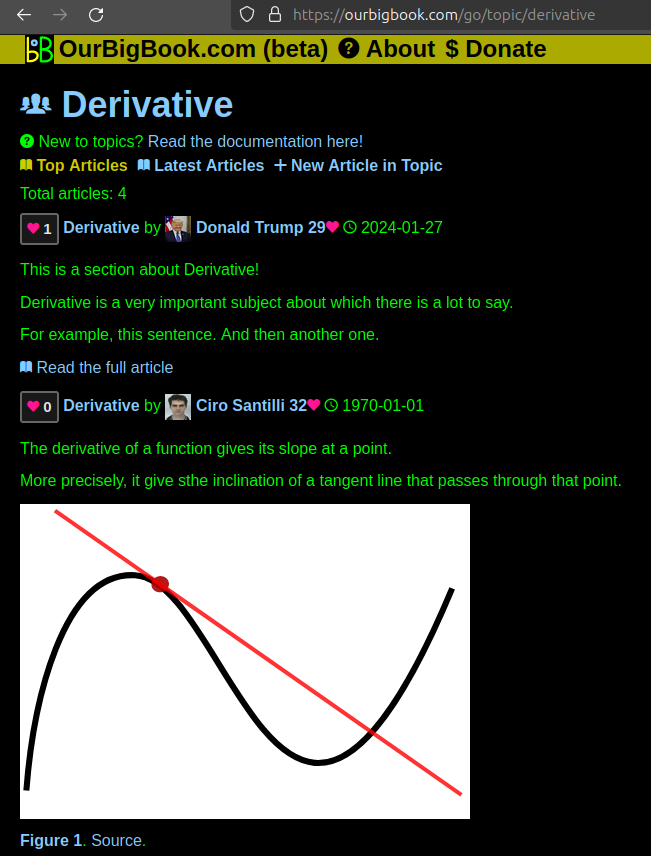

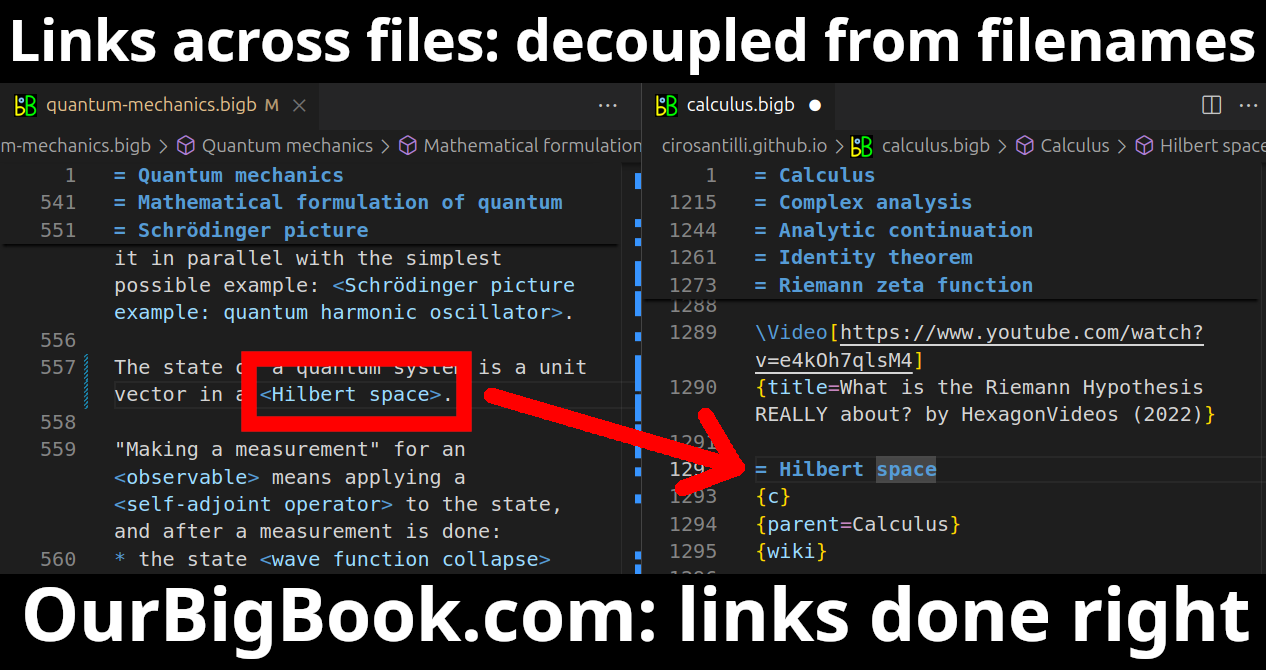

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

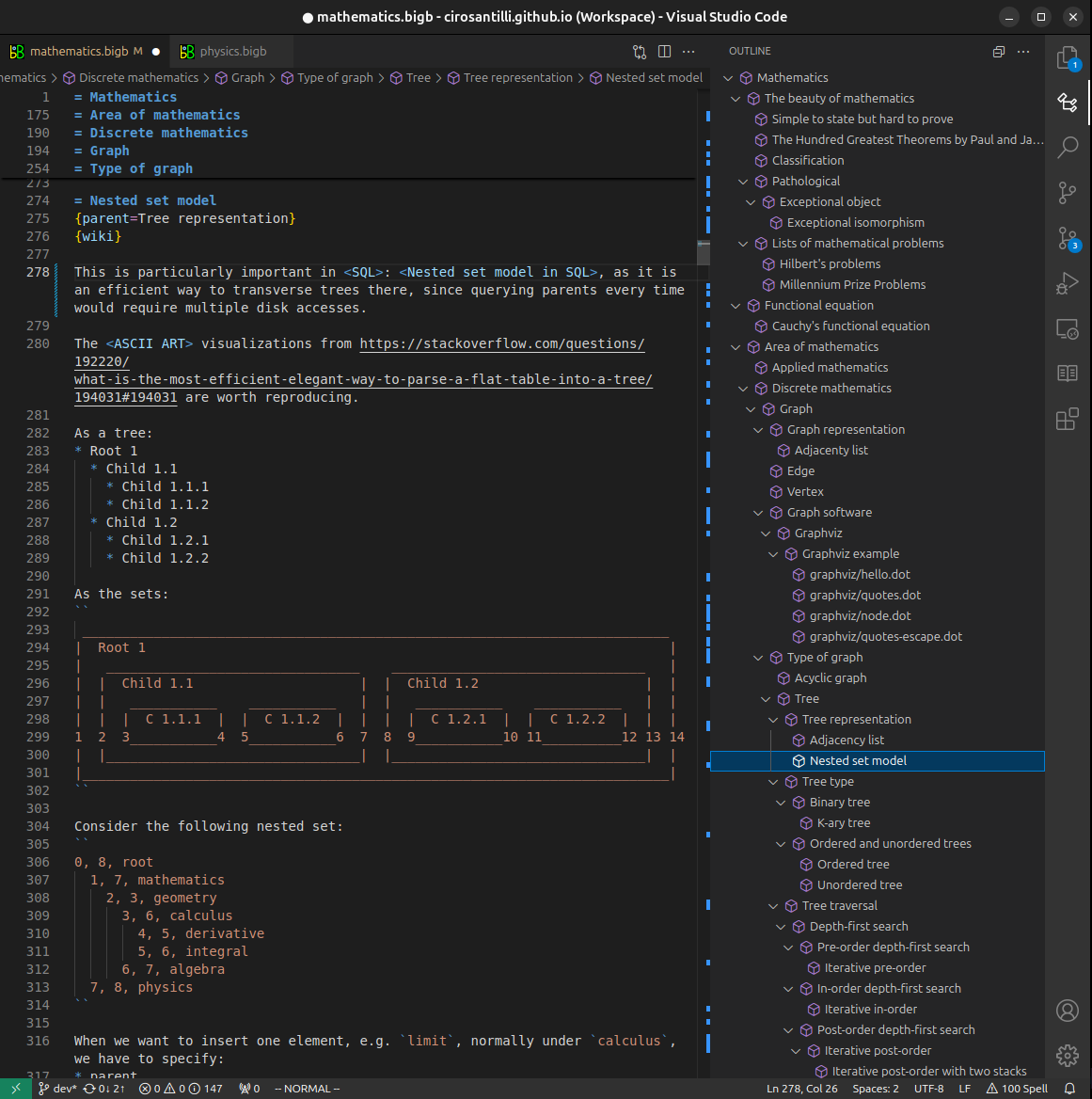

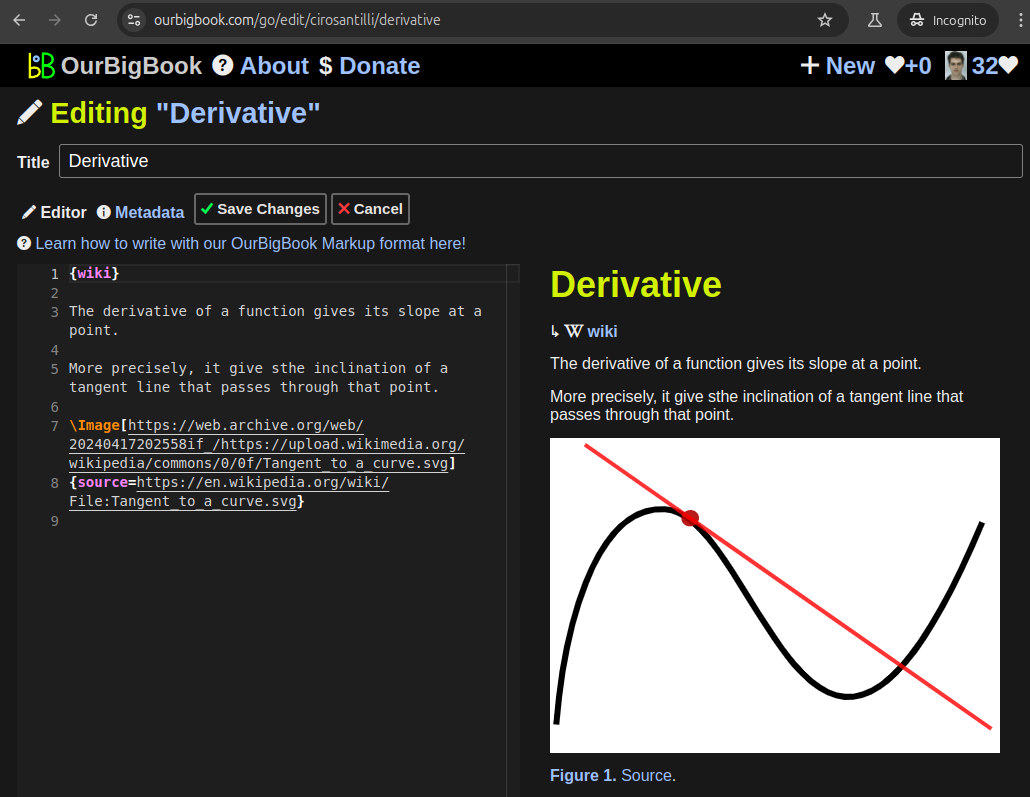

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact