The World Year of Physics 2005 was a global celebration of physics, commemorating the 100th anniversary of Albert Einstein's groundbreaking contributions to the field, particularly his theories of special relativity and the photoelectric effect. The initiative aimed to elevate public awareness and appreciation of physics and its significance in understanding the universe, as well as its technological and social impacts.

Corrado Segre (1859–1924) was an Italian mathematician known for his contributions to algebraic geometry and the theory of algebraic curves. He played a significant role in the development of these fields during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Segre made notable advances in the study of projective geometry and the geometry of algebraic varieties, and he was also involved in the foundations of modern algebraic geometry.

The Gunpowder Age refers to the historical period during which gunpowder was developed and began to be used extensively in warfare, significantly changing military tactics and fortifications. Here is a timeline highlighting key events related to the development and use of gunpowder: ### Timeline of the Gunpowder Age **9th Century:** - **c.

Frances Kirwan is a prominent British mathematician known for her contributions to the fields of algebraic geometry and topology. She is a professor at the University of Oxford and has gained recognition for her work on topics such as moduli spaces and geometric representation theory. Kirwan has also played a significant role in promoting mathematics, particularly through her involvement in various educational initiatives and outreach efforts aimed at increasing diversity in the mathematical sciences.

Alexander Givental is a prominent mathematician known for his work in various areas of mathematics, particularly in algebraic geometry and symplectic geometry. He is recognized for contributions to the field of mirror symmetry, a concept that relates complex algebraic varieties to symplectic manifolds, and for his work on Gromov-Witten invariants, which count curves in algebraic varieties.

David A. Cox is a mathematician known for his work in algebraic geometry, commutative algebra, and computational mathematics. He has authored several influential books and papers in these fields, including works that focus on algebraic varieties, schemes, and intersection theory. He is also involved in educational efforts, providing resources and materials that help students and researchers understand complex mathematical concepts.

Eric Katz could refer to multiple individuals, as it is not an uncommon name. However, one prominent figure by that name is a political journalist known for his work in various media outlets. He has reported on topics such as government, policy, and national security. If you have a specific context or field in mind (e.g., journalism, academics, etc.

Jean-Pierre Demailly is a prominent French mathematician known for his contributions to complex geometry, particularly in the areas of Kähler geometry and the study of several complex variables. He has worked on various topics, including the theory of L2-cohomology, positivity of line bundles, and the theory of special metrics, such as Kähler metrics.

Karl-Otto Stöhr is a German physicist and researcher known for his contributions to the field of condensed matter physics and materials science. He has a distinguished career and has been involved in various advanced research projects, particularly concerning the properties and behaviors of materials at the microscopic level. His work often overlaps with topics in nanotechnology and solid-state physics.

Geoffrey Horrocks is a mathematician known for his contributions to the fields of algebraic geometry and commutative algebra. He has published works on various topics within these areas, focusing on the structure of algebraic varieties and the connections between geometry and algebra. Horrocks is also known for his educational contributions, having worked as a lecturer and educator in mathematics. His insights and research have influenced both theoretical aspects of mathematics and practical applications.

Shigeru Mukai is a Japanese mathematician known for his contributions to algebraic geometry and related fields. He has made significant contributions to various areas, including the study of Fano varieties, the theory of algebraic surfaces, and the interplay between algebraic geometry and number theory.

Jaap Murre is a figure known in the field of bioinformatics and computational biology, particularly for his work on the analysis of DNA sequences and gene mapping. He may also be involved in research related to the structure and function of genomes, and his contributions often bring insights into evolutionary biology and genetics.

Marie-Françoise Roy is a French mathematician noted for her work in mathematical analysis, particularly in the areas of functional analysis and harmonic analysis. She has made significant contributions to the study of linear operators and the theory of distributions.

Kiran Kedlaya is a prominent mathematician known for his work in number theory, algebra, and combinatorics. He has made significant contributions to various fields within mathematics, particularly in areas involving arithmetic geometry, p-adic analysis, and computational complexity. Kedlaya is also recognized for his research on algorithms related to polynomial equations and for his work with the Langlands program.

Kyoji Saito is a Japanese figure known for various contributions in fields such as science, technology, and possibly the arts or culture. However, there isn't a widely recognized individual by that name in popular culture or historical contexts as of my last knowledge update in October 2023. If you have a specific context or field in mind, such as a particular discipline (like literature, technology, etc.

Laurent Lafforgue is a French mathematician known for his work in number theory and algebraic geometry. He was born on February 18, 1966, and is particularly recognized for his contributions to the Langlands program, a set of conjectures and theories relating number theory and representation theory. Lafforgue gained significant acclaim for proving the Langlands conjecture for function fields, which are analogous to number fields but defined over finite fields.

Michele de Franchis might not be widely recognized in popular culture or historical references, and there isn't significant relevant information available as of my last update in October 2023. It's possible he could be a lesser-known figure in a specific field or context.

Miles Reid is a prominent British mathematician, known for his work in the fields of algebraic geometry and topology. He has made significant contributions to the study of complex manifolds and algebraic varieties. Reid is also recognized for his work on the Minimal Model Program, which is a major area of research in algebraic geometry that deals with the classification of algebraic varieties. In addition to his research, Miles Reid has been involved in teaching and mentorship, impacting the academic careers of many students.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

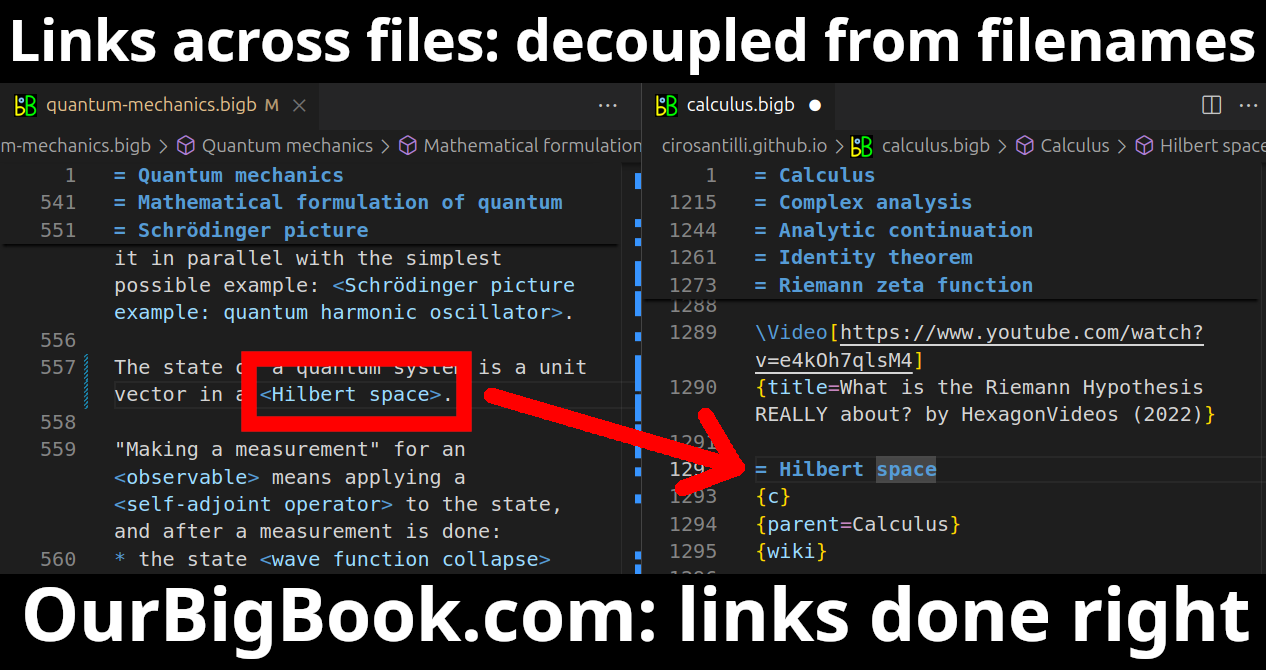

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

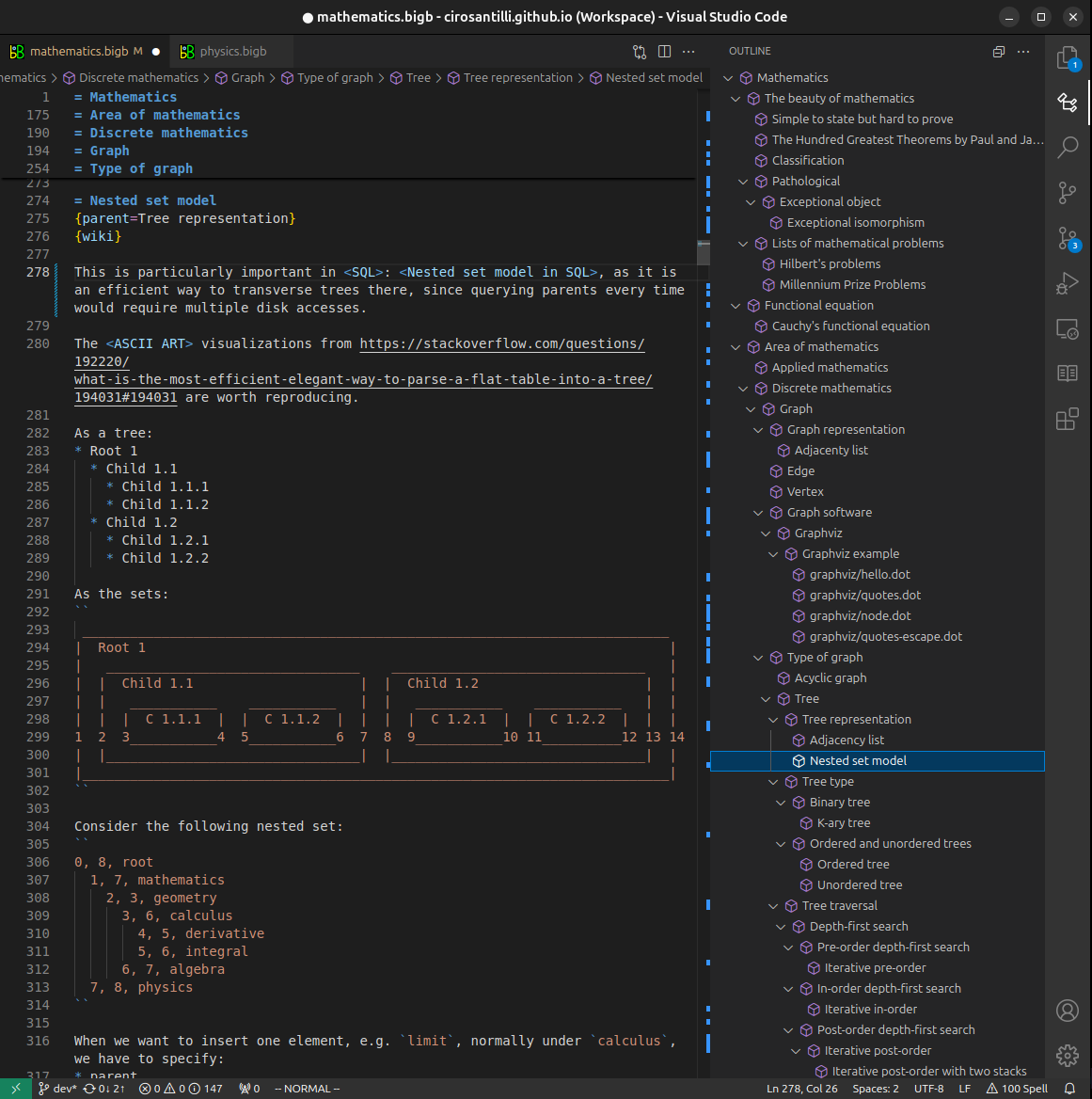

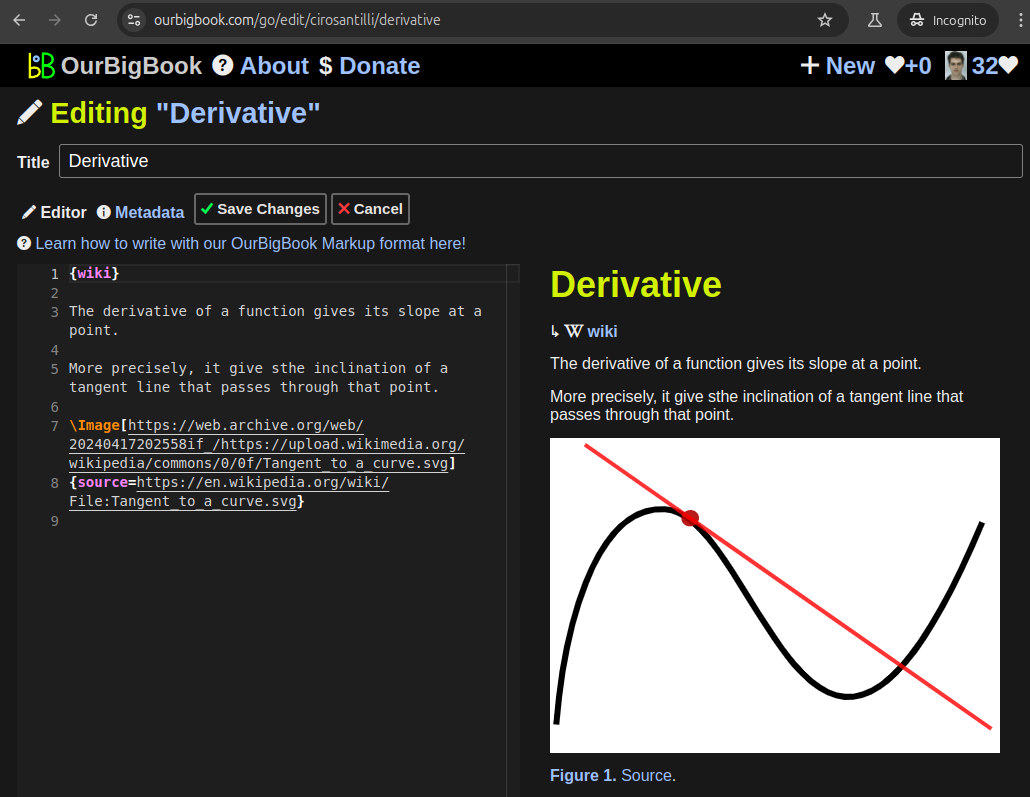

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact