A spiral wave is a type of wave pattern that occurs in various physical and biological systems. It is characterized by a spiraling configuration that can propagate outward in a circular or spiral shape. Spiral waves are commonly observed in several contexts, including: 1. **Physics**: In fluid dynamics, spiral waves can appear in scenarios such as vortex structures in turbulent flows.

The Steinitz Exchange Lemma is a result in combinatorial geometry and convex geometry, particularly related to the concepts of polytopes and their properties. It is named after the mathematician Ernst Steinitz. The lemma provides a foundation for understanding properties related to the exchange of vertices in polytopes and helps in establishing connections between the combinatorial and geometric structures of these shapes.

The Infantry Shoulder Cord, also known as the Infantry Blue Cord, is a distinctive piece of military insignia worn by soldiers in the United States Army who are part of the infantry branch. It is a representation of the soldier's affiliation with the infantry and is typically worn on the right shoulder of the uniform. The cord is made of blue and white braid and is worn as part of the Army uniform, particularly with the Army Service Uniform (ASU).

Sprang is a textile technique that involves creating fabric through interlacing threads in a way that produces a flexible and stretchy material. This technique is characterized by its use of a set of longitudinal threads (the warp) and a series of crossing threads (the weft), which are often manipulated in a specific pattern to create intricate designs. Historically, sprang was used in various cultures for making items such as bags, hats, and other forms of clothing.

In mathematics and dynamical systems, **cycles** and **fixed points** are important concepts related to the behavior of functions and iterative processes.

The stable matching polytope is a geometric representation of the set of all stable matchings in a bipartite graph, where one set of vertices represents one group (such as men) and the other set represents another group (such as women). The concept is closely tied to the stable marriage problem, which seeks to find a stable match between two equally sized groups based on preferences.

Ergodic Ramsey theory is a branch of mathematics that combines ideas from ergodic theory and Ramsey theory to study the interplay between dynamical systems and combinatorial structures. It focuses on understanding the behavior of systems that undergo repeated iterations or transformations over time, particularly in the context of finding regular patterns or structures within them. ### Key Concepts: 1. **Ergodic Theory**: This is a field of mathematics that studies the long-term average behavior of dynamical systems.

In the context of Ramsey theory, a "large set" typically refers to the concept of a set that is sufficiently large or infinite to allow for certain combinatorial properties to emerge. Ramsey theory is a branch of mathematics that studies conditions under which a certain structure must appear in any sufficiently large sample or arrangement. The most famous results in Ramsey theory revolve around the idea of partitioning a large set into smaller subsets.

The theorem you are referring to is likely the "Friendship Theorem," which is often discussed in the context of social networks and combinatorial mathematics. It is sometimes informally summarized as stating that in any group of people, there exist either three mutual friends or three mutual strangers. More formally, the theorem is stated in the context of graph theory.

Non-trophic networks refer to ecological networks that involve interactions among organisms that do not directly relate to feeding or energy transfer (trophic interactions). In contrast to trophic networks, which focus on who eats whom and how energy flows through an ecosystem, non-trophic networks comprise various other types of interactions, such as: 1. **Mutualism:** Interactions where both species benefit, such as pollination relationships between flowering plants and their pollinators (e.g., bees and flowers).

The term "special hypergeometric functions" typically refers to a family of functions that generalize the hypergeometric function, which is a solution to the hypergeometric differential equation.

The Goodwin–Staton integral is a specific integral that arises in certain areas of analysis, particularly in relation to the study of functions defined on the real line and their properties. While there is limited detailed information available about this integral in standard texts, it is generally categorized under a class of integrals that may involve special functions or techniques used in advanced mathematical analysis.

Legendre form typically refers to a representation of a polynomial or an expression in terms of Legendre polynomials, which are a sequence of orthogonal polynomials that arise in various areas of mathematics, particularly in solving differential equations and problems in physics.

The Q-function, or action-value function, is a fundamental concept in reinforcement learning and is used to evaluate the quality of actions taken in a given state. It helps an agent determine the expected return (cumulative future reward) from taking a particular action in a particular state, while following a specific policy thereafter.

The Selberg integral is a notable result in the field of mathematical analysis, particularly in the areas of combinatorics, probability, and number theory. It is named after the mathematician A. Selberg, who introduced it in the context of multivariable integrals.

The Strömgren integral is a concept used in the field of astrophysics, particularly in the study of ionized regions around stars, known as H II regions. It was introduced by the Swedish astronomer Bertil Strömgren in the 1930s. The Strömgren integral refers specifically to the calculation of the ionization balance in a gas that is exposed to a source of ionizing radiation, such as a hot, massive star.

Hall's Marriage Theorem is a result in combinatorial mathematics, specifically in the area of graph theory and bipartite matching. It provides a necessary and sufficient condition for the existence of a perfect matching in a bipartite graph.

Combinatorics of finite geometries is a field of study that explores the properties, structures, and configurations of geometric systems that are finite in nature. It combines principles from combinatorics—the branch of mathematics concerned with counting, arrangement, and combination of objects—with geometric concepts. Here are some key aspects of the combinatorics of finite geometries: 1. **Finite Geometries**: Finite geometries are geometric structures defined over a finite number of points.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

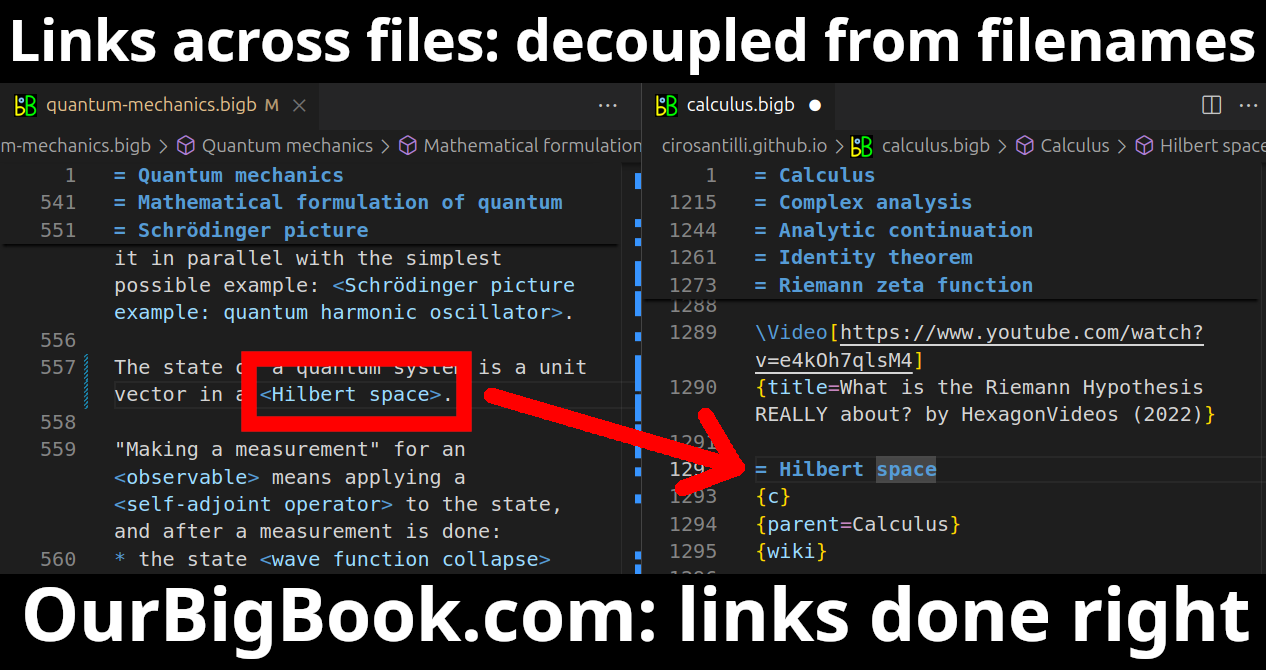

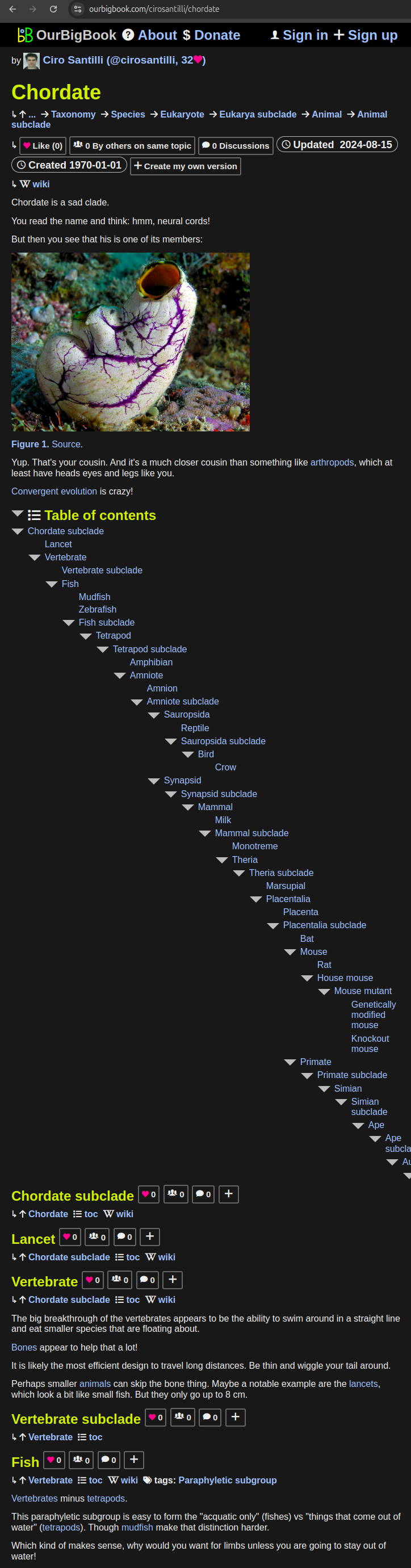

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

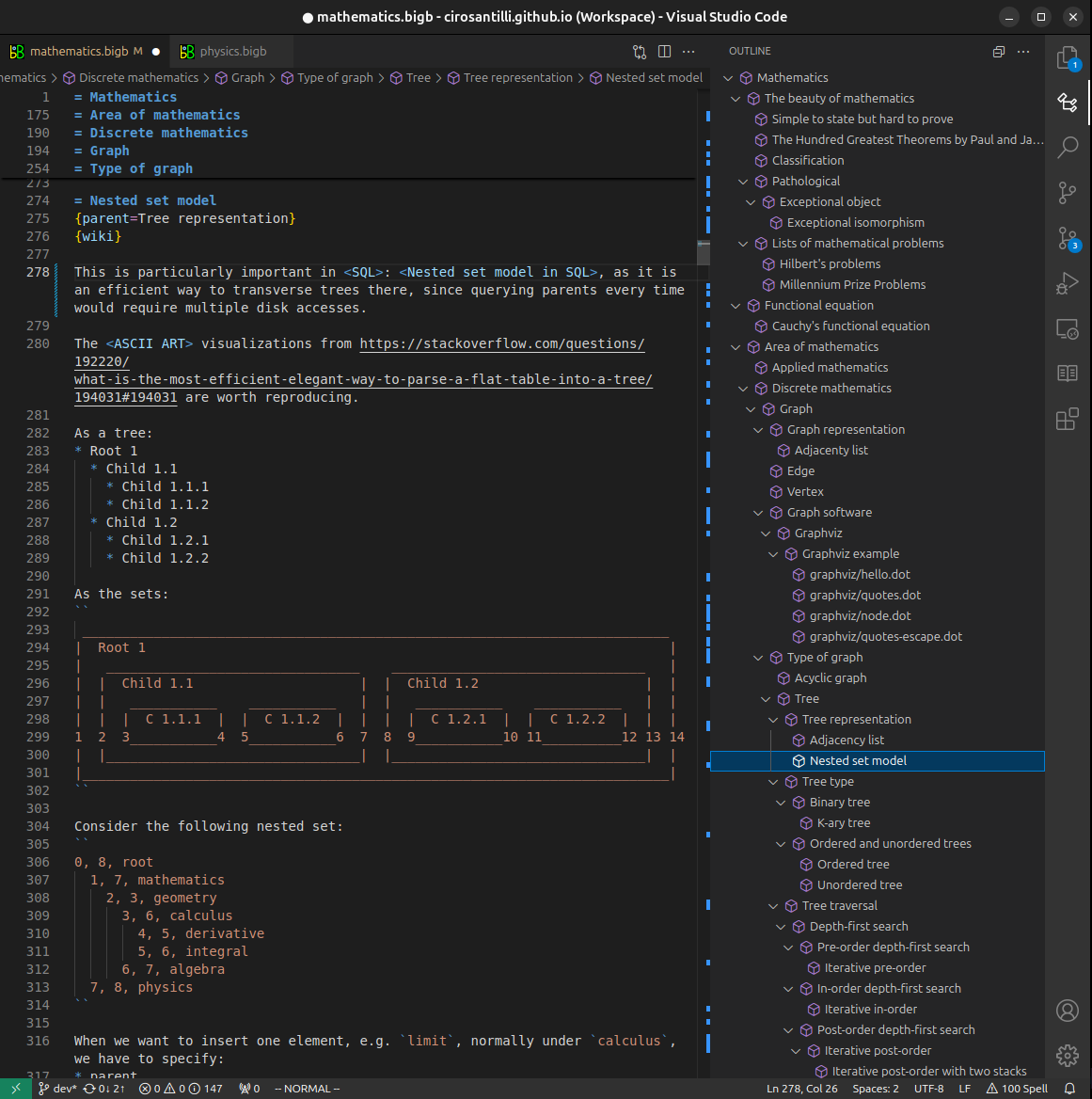

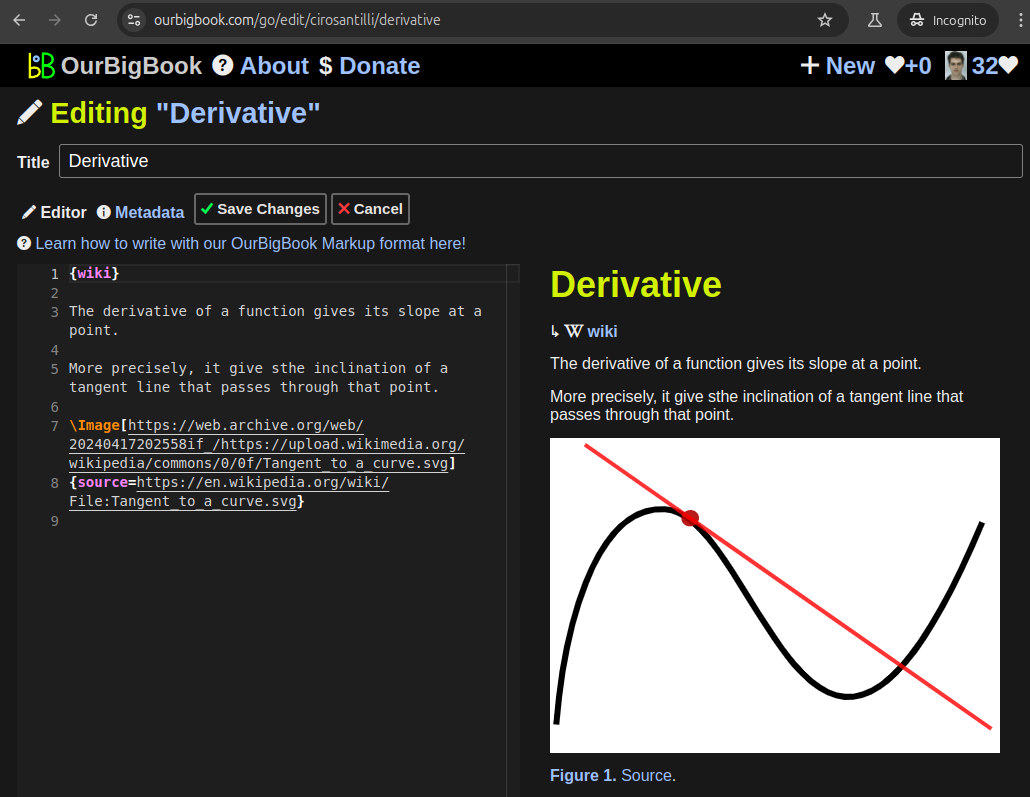

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact