Quantum memory refers to a type of storage system that can hold quantum information, which is information represented by quantum bits or qubits. Unlike classical bits, which can exist in one of two states (0 or 1), qubits can exist in a superposition of states, allowing them to store much more information and enabling more complex computations. Key features of quantum memory include: 1. **Coherent Storage**: Quantum memory must store quantum states without erasing or decohering them.

An "artificial brain" generally refers to advanced computational systems designed to simulate the functions of the human brain. This concept encompasses a range of technologies and disciplines, including artificial intelligence (AI), neural networks, and brain-computer interfaces. Here are some key aspects: 1. **Artificial Intelligence**: AI systems aim to replicate cognitive functions like learning, reasoning, and problem-solving, although they are not modeled on neural structures in a direct way.

Uncomputation is a concept in computer science that refers to the process of effectively "reversing" the computation of a function to retrieve the input from the output, or to erase the information stored during computations in an efficient manner. This idea is particularly relevant in quantum computing and the study of reversible computation, but it has implications in classical computing as well. In reversible computation, every step of the computation can be undone, leading to the possibility of uncomputing intermediate states.

In the context of logic, "convergence" can refer to different concepts depending on the specific area of study. Here are a few interpretations: 1. **Convergence in Proof Theory**: In proof theory, convergence can be discussed in terms of proof reduction. A sequence of logical formulas or proofs may be said to converge if they ultimately lead to the same conclusion or if they simplify to a final form.

"Overlap" in the context of term rewriting refers to situations where two or more rewrite rules can be applied to the same term or expression, leading to different potential outcomes. In term rewriting systems, a rewrite rule typically has the form of a pattern that can match a term and an associated replacement for that term. When more than one rule can be applied to a given term, we say that the rules "overlap.

The Z-spread, or zero-volatility spread, is a measure used in fixed income securities to provide insight into the relative value of a bond over the risk-free rate. It represents the constant yield spread that an investor would receive over the entire term structure of spot rates of a benchmark risk-free rate (often government treasury rates) if the bond's cash flows were discounted using these spot rates.

Epidemiology is the scientific study of the patterns, causes, and effects of health and disease conditions in defined populations. It plays a crucial role in public health by helping to identify risk factors for disease, determining how diseases spread, and developing strategies to control and prevent them. Key aspects of epidemiology include: 1. **Descriptive Epidemiology**: This involves summarizing the health status of populations and identifying trends by examining who, what, when, and where of disease incidence.

The Federal Institute for Population Research (Bundesinstitut für Bevölkerungsforschung, BiB) is a research institute based in Germany that focuses on demographic research and population studies. It operates under the Federal Ministry of the Interior and Community and is dedicated to the analysis of population dynamics, demographic trends, and their implications for society. The institute conducts various research projects, collects demographic data, and provides expertise on issues related to population development, migration, fertility, aging, and other demographic changes.

The Gompertz function is a specific mathematical function often used to model growth processes, particularly in biology and demography. It is named after Benjamin Gompertz, who introduced it in the 19th century. The Gompertz function is particularly useful for modeling the growth of populations and the spread of diseases, as well as for describing the life span of organisms.

Hellin's law, often referred to in the context of sports science and aging, describes a principle related to the decline in performance as athletes age. Specifically, it suggests that for most fundamental physical capacities, such as running speed, strength, and agility, there is a predictable decline associated with aging. This decline is typically around 1% per year after reaching peak performance, which is generally considered to occur in the late 20s to early 30s.

Population density is a measurement of the number of people living per unit of area, typically expressed as individuals per square kilometer or per square mile. It is calculated by dividing the total population of a specific area by the area of that region. This metric helps to provide insights into how crowded or sparsely populated a particular location is. Population density can have significant implications for various aspects of urban planning, resource management, infrastructure development, and environmental sustainability.

USAData is a nonprofit organization that provides transparent and accessible information about the U.S. government and its finances. Founded in 2017, it aims to present complex data in a clear and understandable manner, making it easier for citizens to understand how their tax dollars are spent, as well as the workings of government at various levels. The organization compiles data from various sources, including federal, state, and local governments, and presents it through interactive visualizations, charts, and reports.

Corporate finance is a branch of finance that focuses on the financial activities and decisions of corporations. It encompasses a wide range of activities related to managing a company's capital structure, funding, investments, and overall financial strategy. The primary goals of corporate finance are to maximize shareholder value and ensure the company's long-term financial health. Key components of corporate finance include: 1. **Capital Budgeting**: The process of planning and managing a firm's long-term investments.

Fundraising is the process of gathering voluntary contributions of money or resources from individuals, businesses, charitable foundations, or governmental agencies. It is typically conducted by non-profit organizations, charities, or political campaigns to support a specific cause, project, or business operations. Fundraising can take various forms, including: 1. **Events**: Organizing activities such as galas, auctions, fun runs, or concerts to raise money while engaging attendees.

Financial econometrics is a specialized area within econometrics that focuses on the application of statistical and mathematical methods to analyze financial data. It combines principles from finance, economics, and statistics to model and understand financial phenomena, assess risks, and forecast financial variables. Here are some key aspects of financial econometrics: 1. **Modeling Financial Time Series**: Financial econometrics often deals with time series data, such as stock prices, interest rates, or economic indicators, which are collected over time.

Ff phages, also known as filamentous phages, are a type of bacteriophage that infects bacteria, particularly those belonging to the family Enterobacteriaceae. These phages are characterized by their long, thin, filamentous structure, which contrasts with the more commonly known icosahedral or rod-shaped bacteriophages. The most well-studied members of the Ff phage family include Ff, M13, and fd.

Political risk refers to the potential for losses or adverse impacts on investments, business operations, or economic conditions resulting from political decisions, instability, or changes in government policy. This risk can arise from a variety of sources, including: 1. **Government Actions**: Changes in laws and regulations, expropriation of assets, or significant changes in trade policies can create risks for businesses operating in a country.

A Lookback option is a type of exotic financial derivative that allows the holder to "look back" over a predefined period of time and exercise the option based on the optimal price of the underlying asset during that period. This unique feature distinguishes Lookback options from standard options. There are two main types of Lookback options: 1. **Lookback with a maximum:** The payoff is based on the difference between the final price of the underlying asset and its minimum price during the life of the option.

A market correction refers to a short-term drop in the prices of securities, typically defined as a decline of 10% or more from a recent peak in a stock index or individual stock. Corrections are considered a natural part of the market cycle and occur after a significant rally or period of price increases. Market corrections can be triggered by a variety of factors, including: 1. **Economic Data**: Poor economic reports or forecasts can lead to decreased investor confidence and selling pressure.

The Markowitz model, also known as Modern Portfolio Theory (MPT), is a framework for constructing an investment portfolio in a way that maximizes expected return for a given level of risk, or alternatively minimizes risk for a given level of expected return. The model was developed by Harry Markowitz, who introduced it in his 1952 paper "Portfolio Selection.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

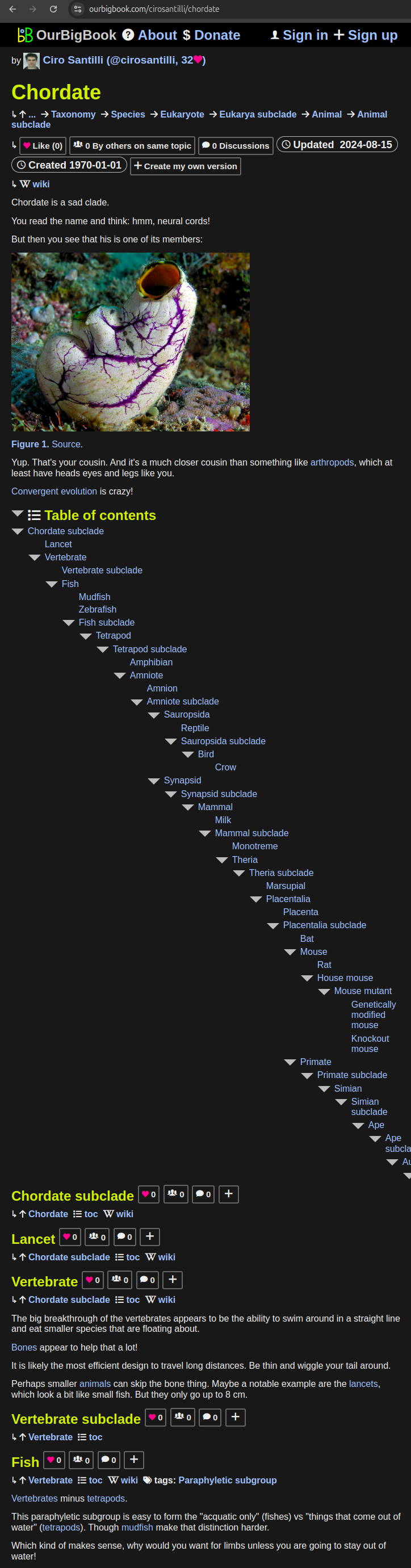

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

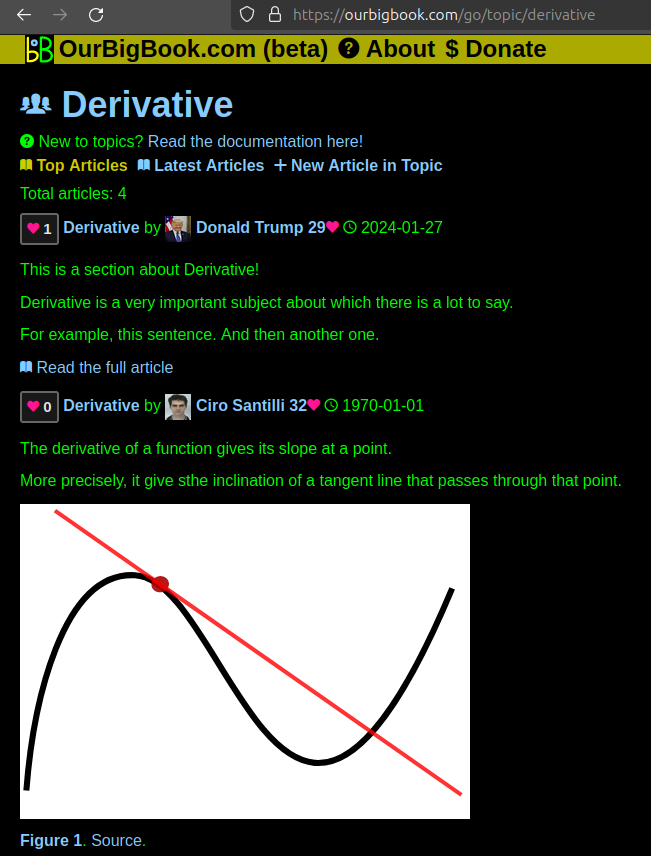

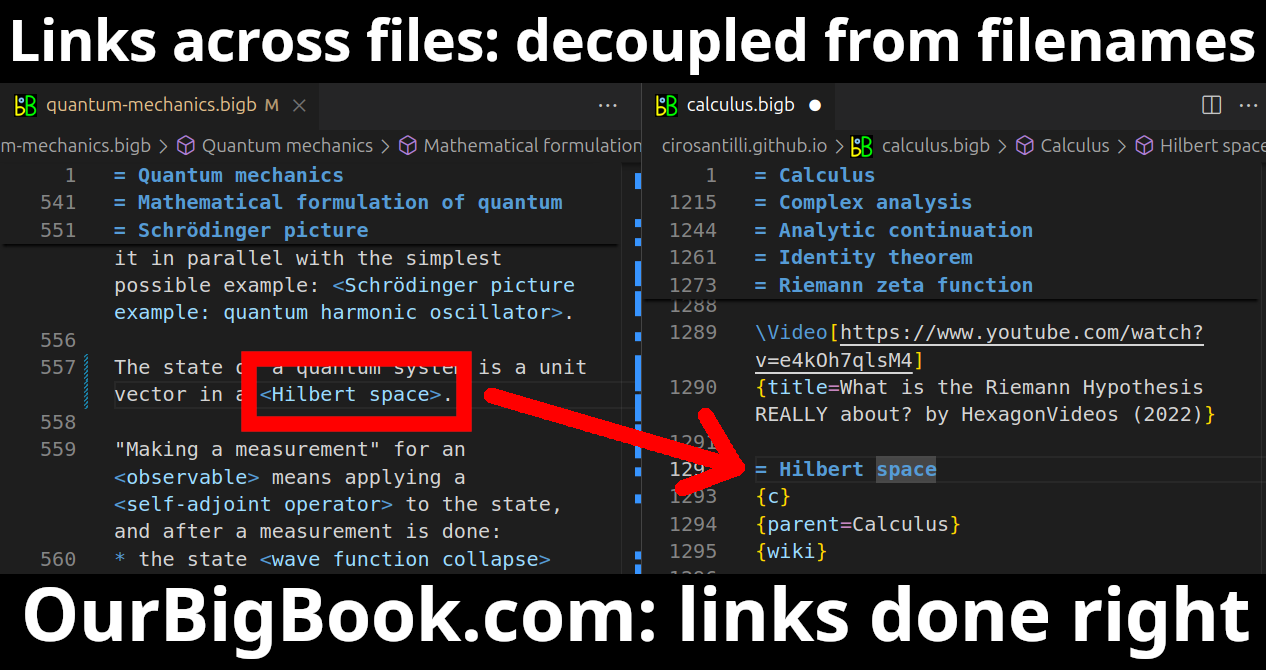

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

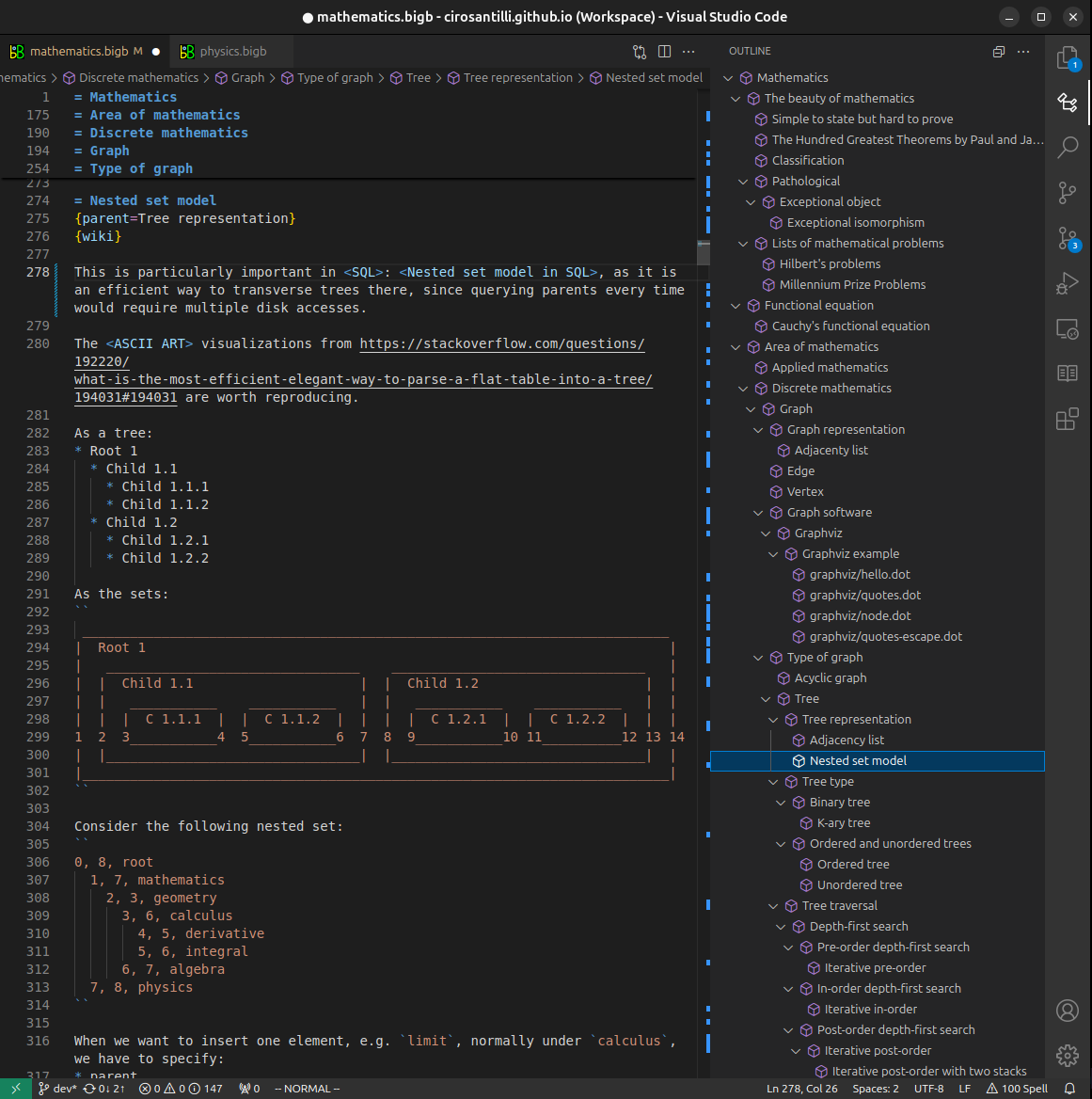

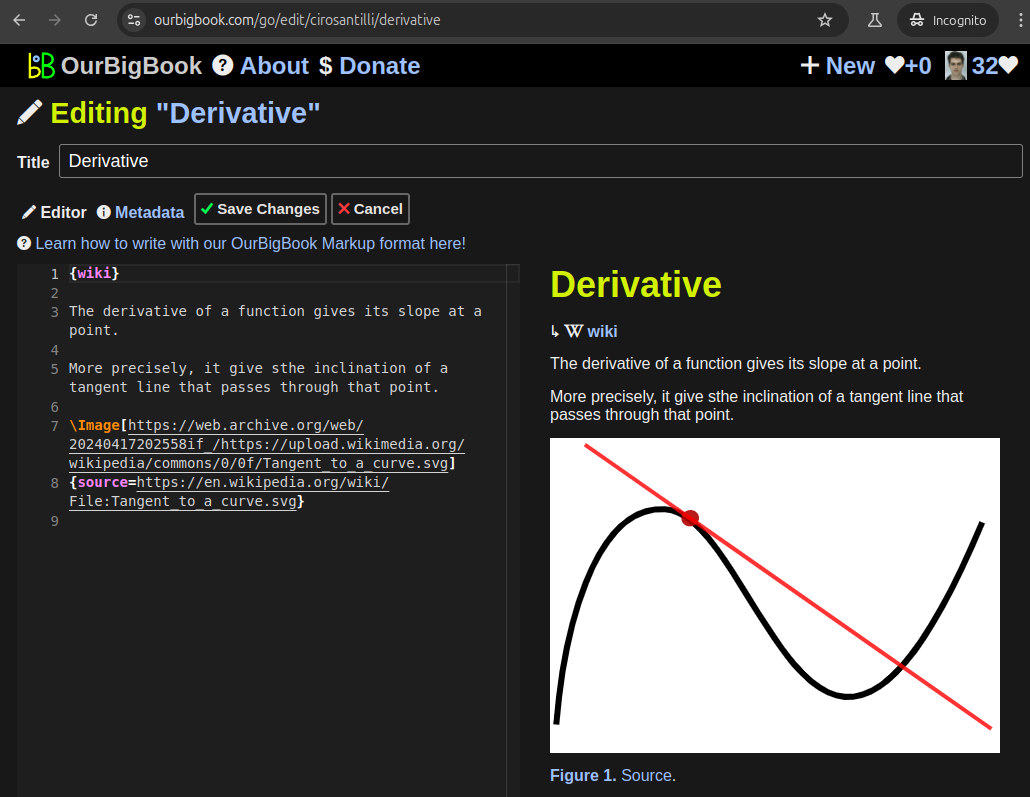

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact