Dino Cube can refer to a few different concepts depending on the context, but it is most commonly associated with a toy or puzzle in the shape of a cube that features dinosaur-themed designs or elements. It can also refer to a specific game or digital application involving dinosaurs and cube mechanics.

Obesity is a medical condition characterized by an excessive accumulation of body fat that presents a risk to an individual's health. It is typically measured using the Body Mass Index (BMI), which is calculated by dividing a person's weight in kilograms by the square of their height in meters (kg/m²). A BMI of 30 or greater is generally considered obese, while a BMI between 25 and 29.9 is classified as overweight.

The Radiation Control for Health and Safety Act of 1968 is a piece of legislation in the United States aimed at protecting public health and safety from the hazards of radiation. The act was part of Congress's efforts to address increasing concerns about the potential dangers posed by electronic products and medical devices that emit radiation.

The thermo-optic coefficient is a parameter that quantifies the change in the refractive index of a material with respect to temperature. It is typically denoted as \(dn/dT\), where \(n\) is the refractive index and \(T\) is the temperature. This coefficient is crucial in applications where temperature variations can affect the optical properties of materials, such as in fiber optics, photonics, and various optical devices.

"Discoveries" by Charles de Saint-Aignan is a notable literary work that highlights various scientific and cultural explorations. However, it seems there might be a confusion or incorrect attribution, as Charles de Saint-Aignan (also known as Charles de Saint-Aignan le jeune) is not widely recognized as the author of a well-known work titled "Discoveries.

"Discoveries" is a book by Edward Emerson Barnard, an American astronomer known for his groundbreaking work in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The book, published in 1927, compiles Barnard's observations and discoveries related to astronomy, particularly his work on planets, comets, and other celestial phenomena.

"Discoveries" by François Dossin is a project that focuses on exploration and innovation, often highlighting themes related to art, science, and the human experience. However, specific details about the project, such as its content or goals, may vary. Typically, Dossin's work may incorporate elements of storytelling, visual art, and multimedia presentations to engage with audiences on various topics.

"Discoveries" by Harry Edwin Wood is a notable work that focuses on various scientific and historical discoveries. Harry Edwin Wood, a writer and educator, explores the impact of these discoveries on society and human understanding. The book delves into different fields such as physics, biology, archaeology, and more, presenting significant milestones in each area and the individuals behind them.

"Discoveries" is a book written by Joseph Masiero, which explores various themes and concepts related to human experiences, discoveries, and insights. While specific details about the book may vary, it often focuses on the intersection of personal growth, scientific inquiry, and philosophical reflections.

"Discoveries" is a work by Koichi Itagaki, who is a well-known Japanese manga artist best recognized for his popular series "Baki the Grappler." Although specifics about "Discoveries" may be limited, Itagaki's style typically involves intense martial arts action, character development, and philosophical exploration of strength and combat.

"Discoveries" by Luigi Volta is not a well-known title or work typically associated with the inventor Alessandro Volta, who was an Italian physicist renowned for his pioneering work in electricity and the invention of the electric battery, known as the Voltaic pile, in the late 18th century.

"Discoveries" by Michael Collins refers to a compilation of significant contributions and findings in the field of astronomy by Michael Collins, an American astronaut and not an astronomer by profession. Collins is best known for his role in the Apollo 11 mission, where he served as the Command Module Pilot alongside astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin.

"Discoveries" by Michał Żołnowski is a work that explores themes related to exploration, innovation, and the impact of discoveries on society and culture. However, as of my last knowledge update in October 2023, there isn't detailed information available about a specific book or piece titled "Discoveries" by Michał Żołnowski. It's possible that it may have gained recognition after that time or that it is a lesser-known work.

"Discoveries" by Norbert Ehring is a publication that presents a collection of innovative ideas or findings, potentially encompassing a range of topics, including science, technology, philosophy, or art. Without more context, it's difficult to provide specific details, as the title may refer to various works or themes explored by the author.

"Discoveries" by Rafael Ferrando is not widely known, and it seems there is limited information available about this specific title or work. It’s possible that it could be a novel, a piece of art, or another form of creative expression by Rafael Ferrando, but without more context, it's difficult to provide accurate information.

TRPV6 (Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid 6) is a protein that functions as an ion channel, primarily permeable to calcium ions (Ca²⁺). It is part of the TRP (Transient Receptor Potential) channel family, which is involved in various sensory processes and physiological functions.

"Discoveries" by William Liller is a book that explores various scientific and technological advancements throughout history. William Liller, an accomplished physicist and educator, delves into significant discoveries, their impact on society, and the individuals behind them. The book typically covers a range of topics, including physics, astronomy, and other fields, highlighting how these breakthroughs have shaped our understanding of the world.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

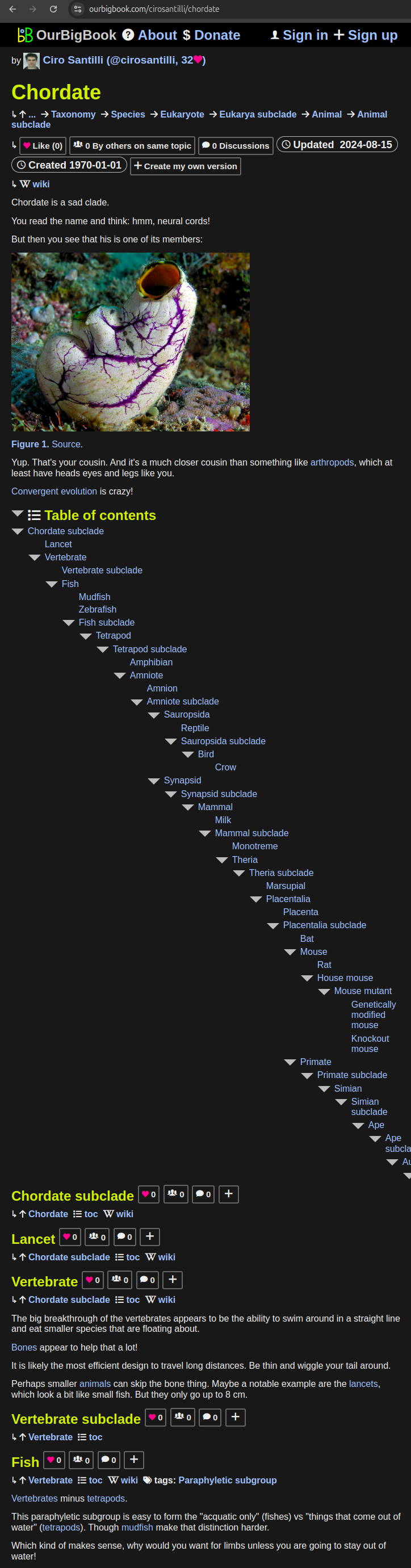

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

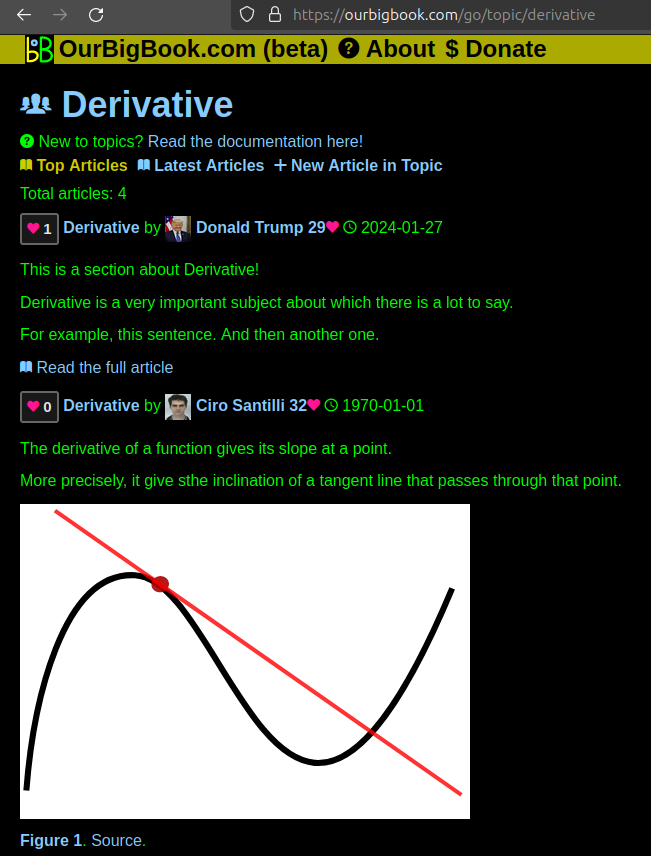

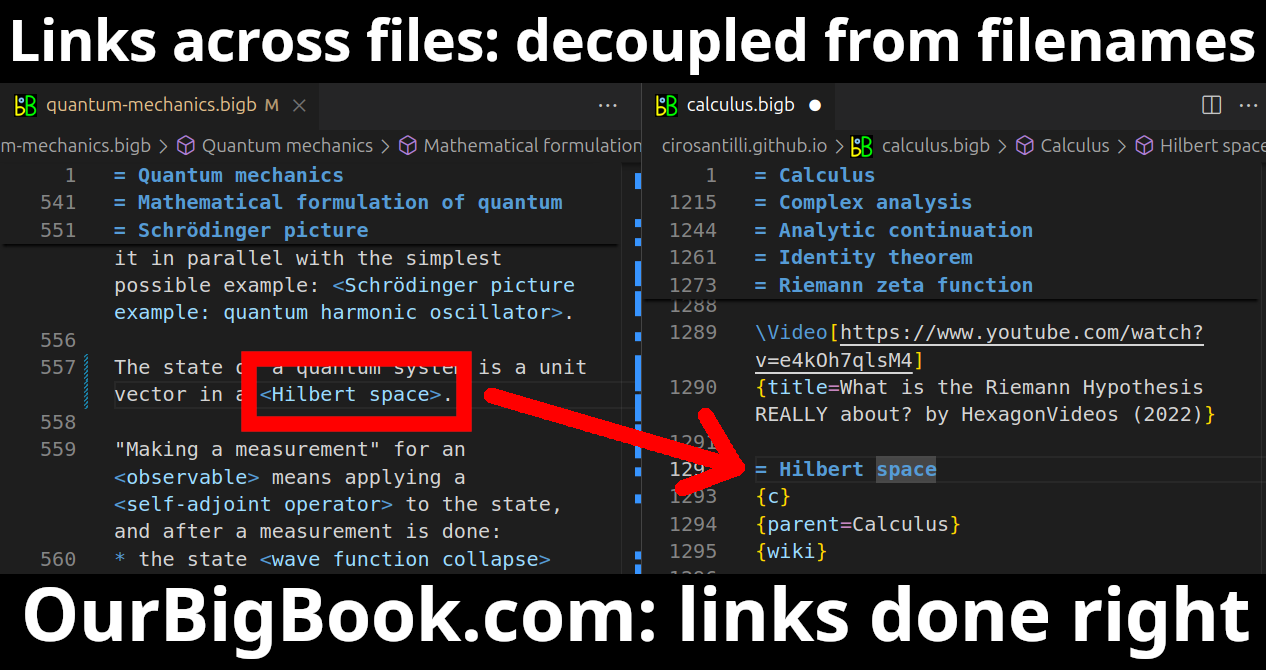

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

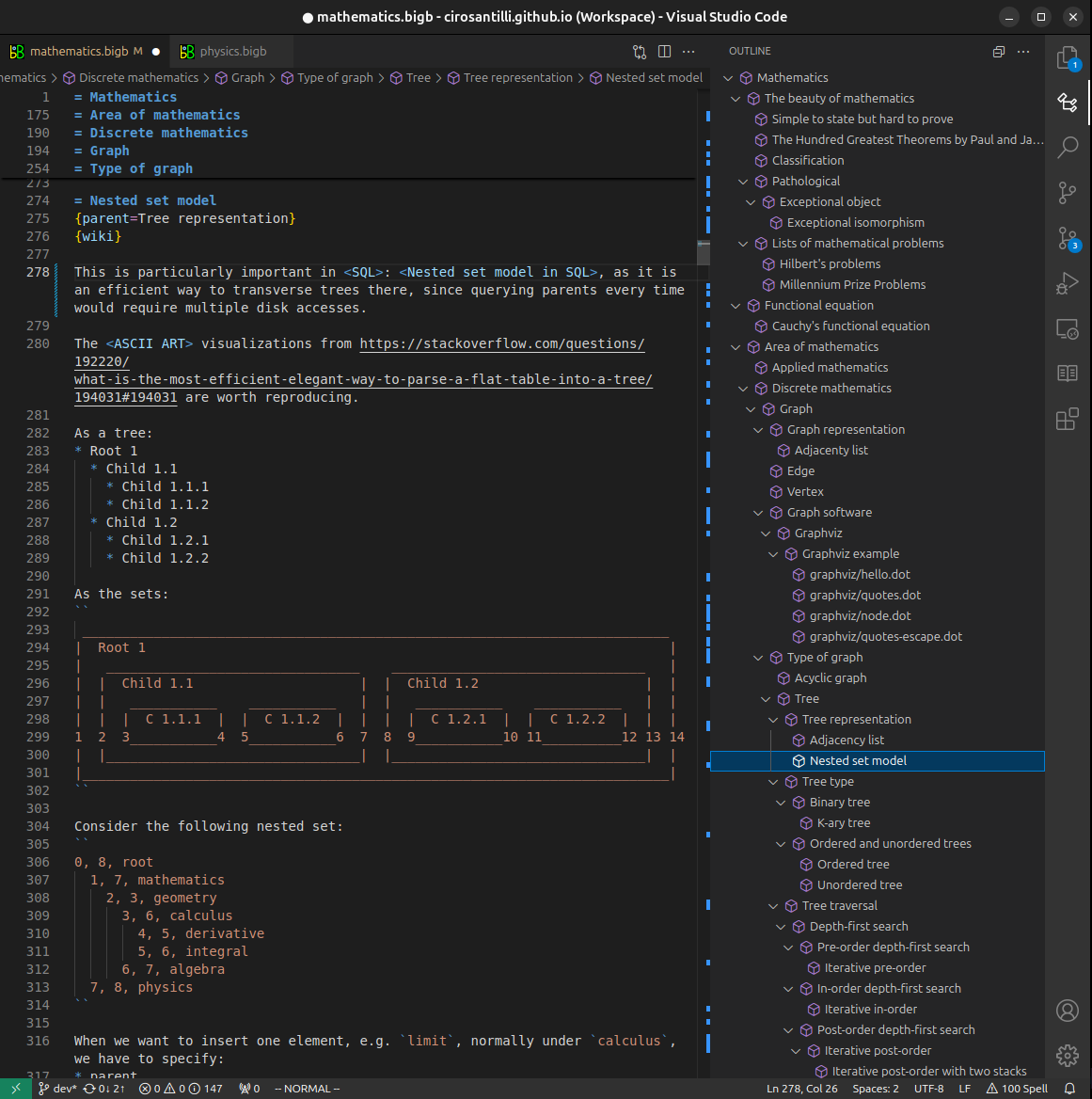

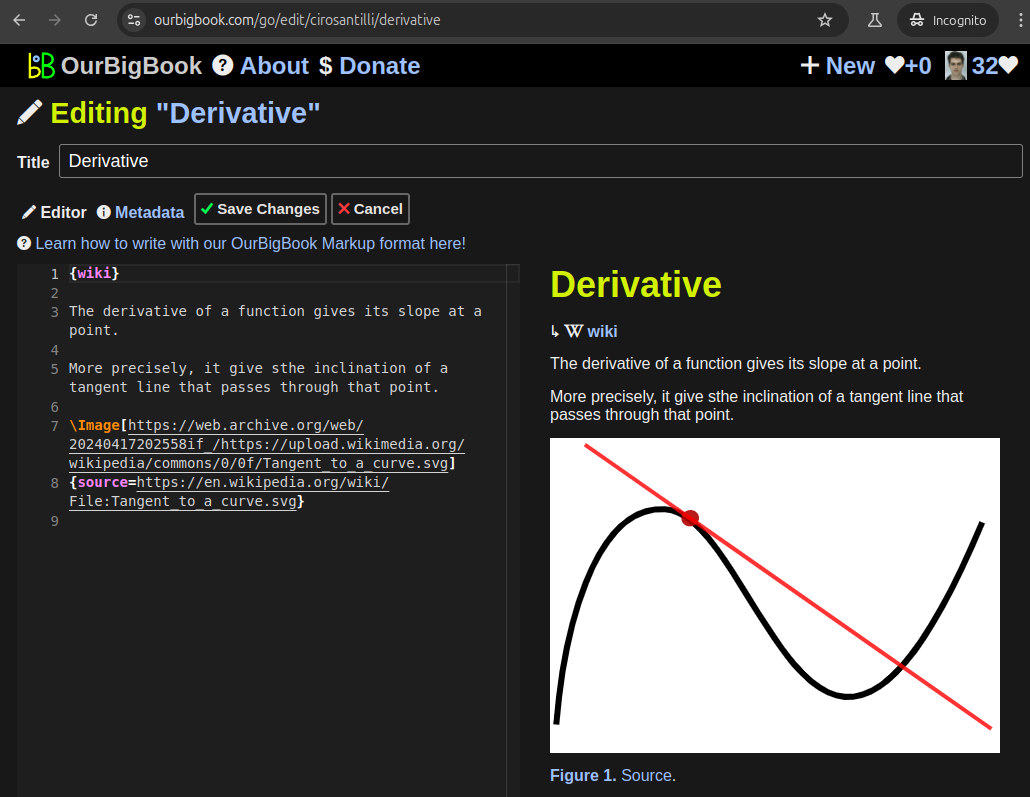

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact