Thomas Bayes (1701–1761) was an English statistician, philosopher, and Presbyterian minister, best known for his contributions to the field of probability and statistics. He is particularly renowned for Bayes' theorem, a fundamental theorem in probability theory that describes the probability of an event based on prior knowledge of conditions related to the event. Bayes' theorem mathematically expresses how to update the probability of a hypothesis as more evidence or information becomes available.

Vyacheslav Vasilievich Sazonov is not a widely recognized figure in global history or culture as of my last knowledge update in October 2023. It's possible that he may refer to a notable individual within a specific context, such as local history, a particular field of study, or a certain profession that hasn't gained widespread recognition.

W. T. Martin may refer to various entities or individuals depending on the context, but one notable mention is W. T. Martin, a company known for manufacturing and supplying a range of products, particularly in the textile and home goods industries. However, without more specific information, it's challenging to determine exactly which W. T. Martin you are referring to.

Zdzisław Józef Porosiński is not a widely recognized public figure, historical person, or concept based on my training data up to October 2023.

The Weil–Petersson metric is a Kähler metric defined on the moduli space of Riemann surfaces. It arises in the context of complex geometry and has important applications in various fields such as algebraic geometry, Teichmüller theory, and mathematical physics. Here's a more detailed overview: 1. **Context**: The Weil–Petersson metric is most commonly studied on the Teichmüller space of Riemann surfaces.

A valid argument form is a logical structure that ensures that if the premises are true, the conclusion must also be true. Here’s a list of some common valid argument forms: 1. **Modus Ponens (Affirming the Antecedent)** - Structure: - If P, then Q. - P. - Therefore, Q. - Example: If it rains, the ground is wet. It is raining. Therefore, the ground is wet.

A typing environment, often referred to in the context of programming languages and type systems, is an abstract framework or model that defines how types are assigned to expressions or variables within a program. It provides a way to understand the relationships between different types and the rules governing their interactions. ### Key Elements of a Typing Environment: 1. **Type Associations**: A typing environment maintains a mapping between variable names (or identifiers) and their respective types.

T. M. Scanlon, or Thomas M. Scanlon, is an American philosopher known for his work in moral philosophy and political philosophy. He has made significant contributions to the understanding of moral reasoning, contractualism, and the nature of rights and obligations.

A compute kernel is a function or a small piece of code that is executed on a processing unit, such as a CPU (Central Processing Unit) or GPU (Graphics Processing Unit), typically within the context of parallel computing. Compute kernels are fundamental to leveraging the capabilities of parallel architectures, allowing applications to perform large-scale computations efficiently.

"Red nugget" can refer to different things depending on the context. Here are some possibilities: 1. **In Geology**: A "red nugget" might refer to a small piece of mineral or ore, particularly one that has a reddish color, such as certain types of copper or iron ore. 2. **Botany**: In gardening terms, "red nugget" could refer to a specific variety of plant, such as a red-leaved shrub or ornamental flower.

Cryptlib is a cryptographic library designed to provide a wide range of encryption and hashing functions to developers and applications. It offers functionalities for both symmetric and asymmetric cryptographic algorithms, as well as support for various cryptographic protocols and standards. Some of the key features typically include: 1. **Encryption Algorithms**: Support for well-known algorithms such as AES, DES, RSA, and more.

A wedge issue is a political or social issue that divides people within a political party or between different political factions, often creating significant disagreement or controversy. These issues can be used strategically by politicians to gain support from specific voter demographics or to highlight divisions within competing parties. Examples of wedge issues often include topics related to abortion, gun control, immigration, and same-sex marriage.

The history of chess engines is a fascinating journey that reflects advancements in computer science and artificial intelligence. Here’s an overview of the significant milestones in the development of chess engines: ### Early Beginnings (1950s-1970s) - **1951-1966**: The first attempts at creating a chess-playing computer program were made in the early 1950s.

Mephisto is a series of chess computers and software developed by the German company Hegener + Glaser, which gained popularity in the 1980s and 1990s. The Mephisto chess computers were among the early dedicated machines designed specifically for playing chess, offering various models that differed in strength and features. The Mephisto brand was known for its innovative technology and design in chess computing.

"Computer chess people" typically refers to individuals who are involved in the development, programming, analysis, and promotion of chess software and artificial intelligence systems designed to play chess. This group may include: 1. **Programmers and Engineers**: These are the developers who create chess engines, which are algorithms capable of evaluating positions, generating moves, and playing chess at various levels of skill. Some well-known chess engines include Stockfish, AlphaZero, and Komodo.

"Mathematical Excursions" typically refers to a book or educational resource that presents mathematical concepts in an engaging and exploratory manner. One well-known example is the textbook "Mathematical Excursions" by Richard N. Aufmann, Joanne Lockwood, and Dennis E. Berg. This book is designed for students in developmental mathematics courses and focuses on fundamental mathematical concepts while integrating real-world applications and problem-solving techniques.

"The Mathematics of Life" can refer to the various ways in which mathematical principles are applied to understand, model, and analyze biological processes and systems. This interdisciplinary field, often explored in mathematical biology, encompasses several key areas: 1. **Population Dynamics**: Mathematical models help understand how populations of organisms grow and interact. The Lotka-Volterra equations, for example, are used to describe predator-prey relationships.

"Principles of the Theory of Probability" typically refers to foundational concepts and rules that govern the field of probability theory. Probability theory is a branch of mathematics that deals with the analysis of random phenomena. The principles can be categorized into several key areas: 1. **Basic Concepts**: - **Experiment**: An action or process that leads to one or more outcomes (e.g., rolling a die).

There are numerous journals dedicated to the field of probability, covering a wide range of topics related to probability theory and its applications. Here’s a list of some prominent probability journals: 1. **The Annals of Probability** - A leading journal that publishes research on probability theory and stochastic processes. 2. **Probability Theory and Related Fields** - Focuses on probability theory and its applications. 3. **Journal of Applied Probability** - Publishes research on applied probability and stochastic processes.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

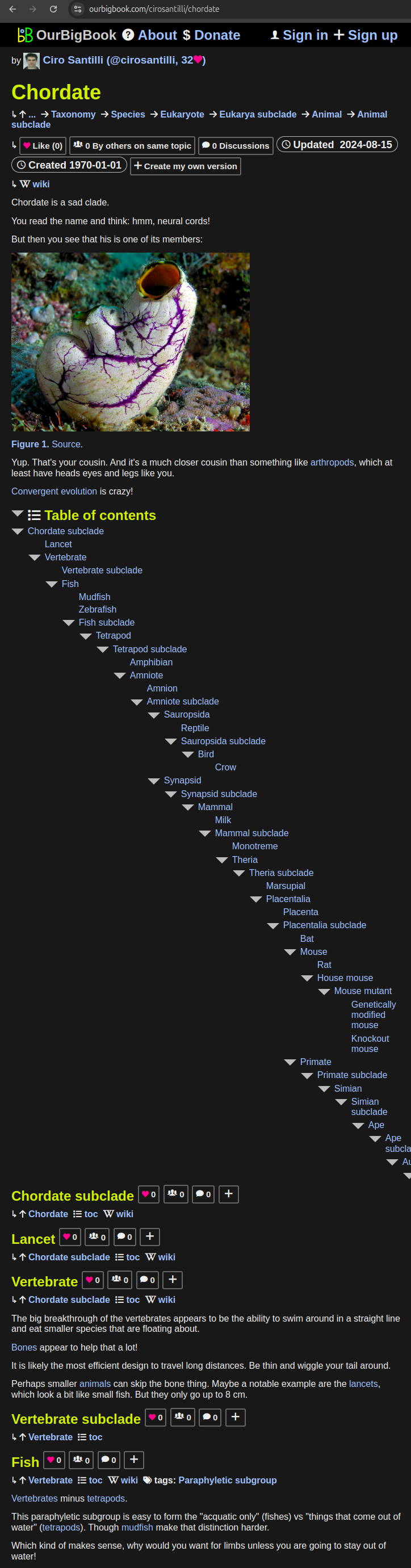

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

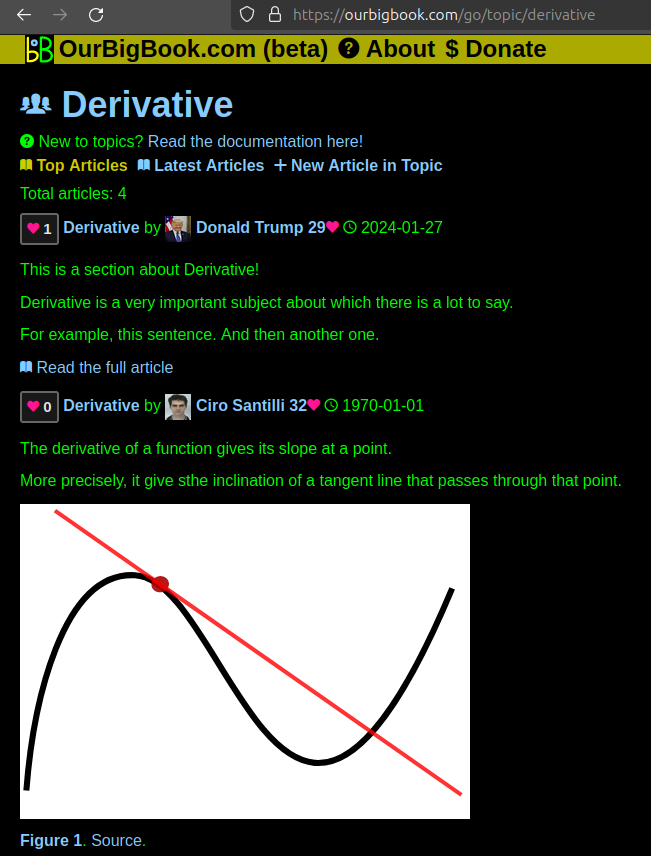

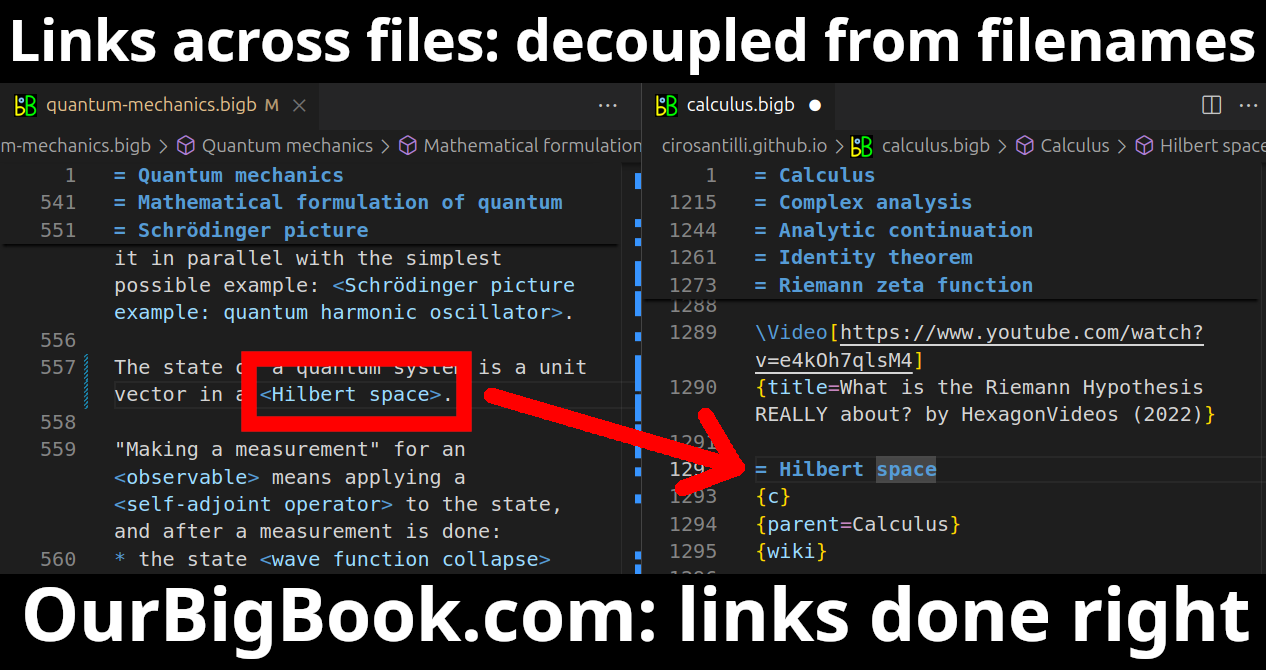

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

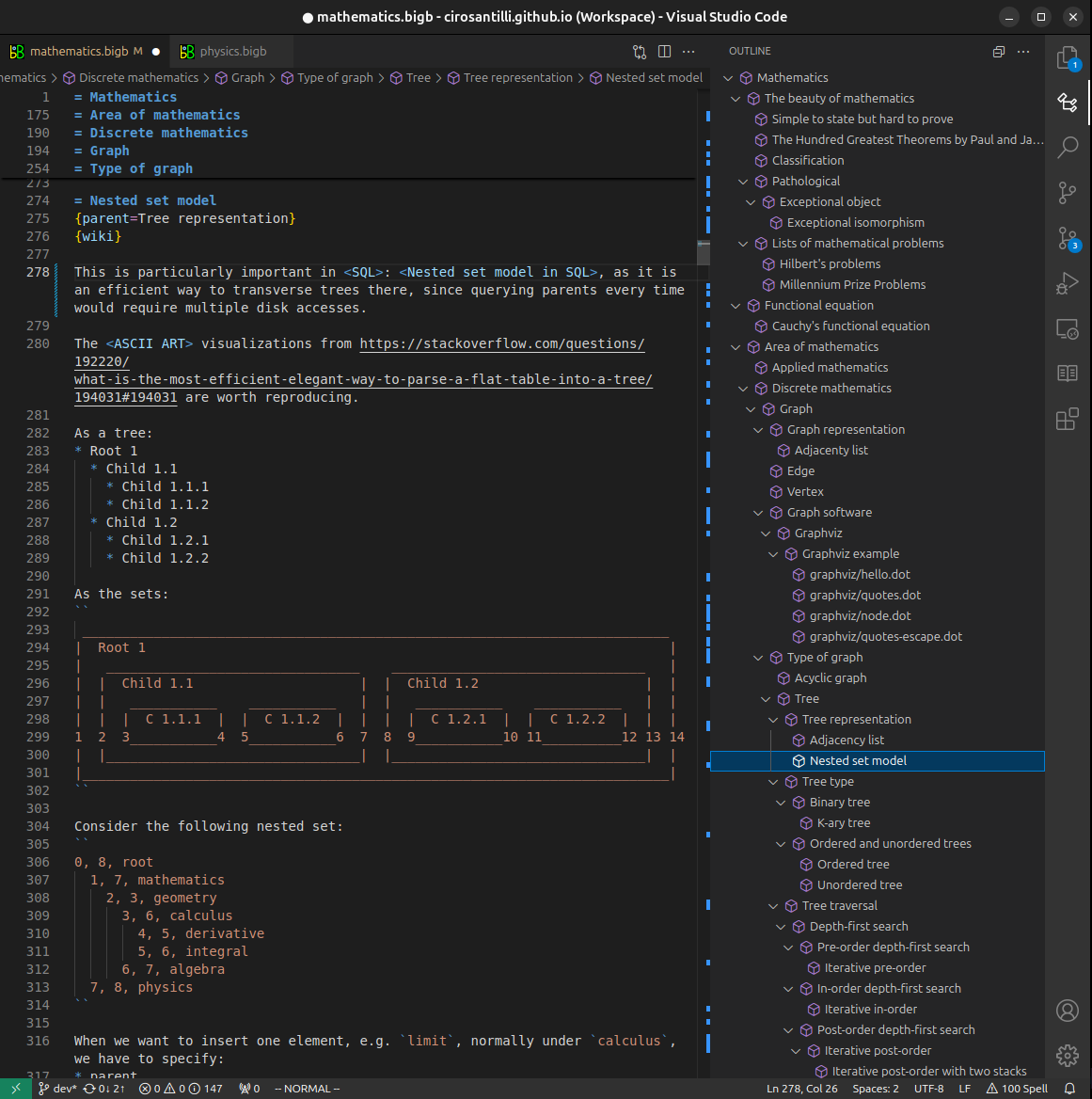

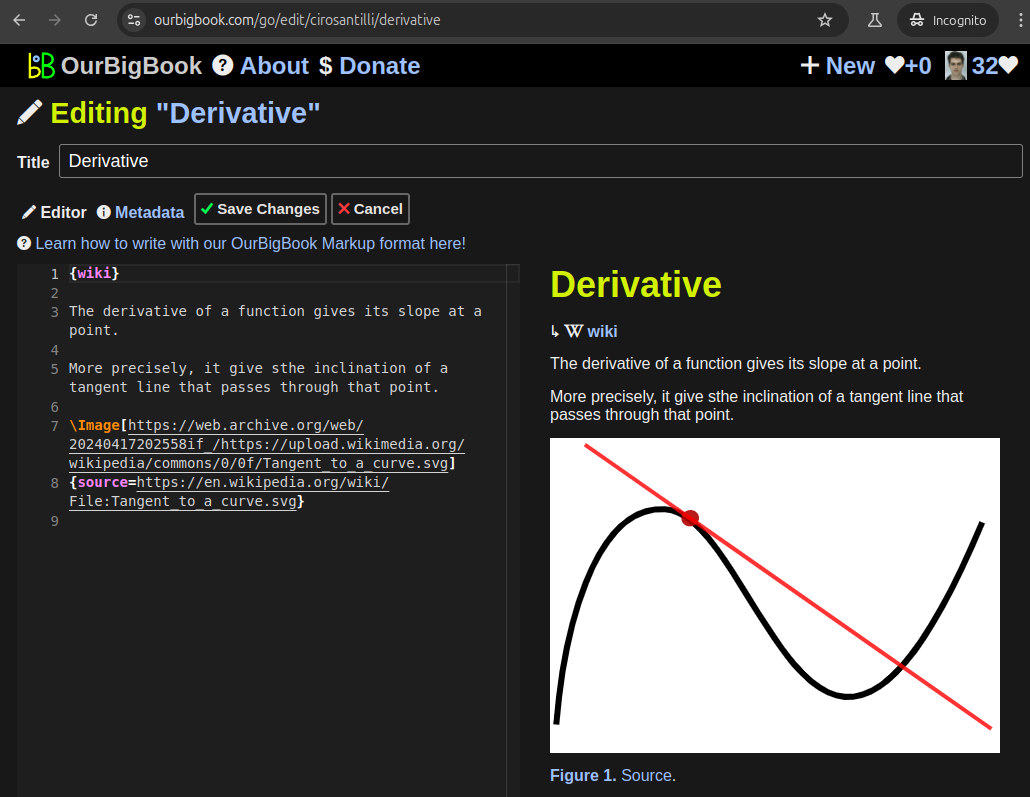

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact