A **numerical semigroup** is a special type of subset of the non-negative integers. Specifically, it is a subgroup of the non-negative integers under addition that is closed under addition and contains the identity element 0. More formally, a numerical semigroup is defined as follows: 1. It is a subset \( S \) of the non-negative integers \( \mathbb{N}_0 = \{0, 1, 2, \ldots\} \).

NUTS (Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics) is a hierarchical system for dividing up the economic territory of the European Union and is used for collecting, developing, and analyzing regional statistics. Hungary is divided into several NUTS regions under this classification. As of the current classifications, Hungary is divided into the following NUTS levels: 1. **NUTS-0**: Hungary itself (the whole country).

Ocean acidification refers to the process by which the pH level of Earth's oceans decreases due to the absorption of excess atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2). As CO2 is emitted into the atmosphere from human activities, such as burning fossil fuels and deforestation, a significant portion of it is absorbed by the oceans. When CO2 dissolves in seawater, it reacts with water to form carbonic acid, which dissociates into bicarbonate and hydrogen ions.

Oceanic freshwater flux refers to the movement of freshwater into and out of oceanic and coastal regions. This flux can occur through various processes, including: 1. **Precipitation**: Rain or snow that falls directly onto the ocean surface adds freshwater to the sea. 2. **River Discharge**: Freshwater from rivers flowing into the ocean contributes to the overall freshwater balance. This is particularly significant in coastal areas where rivers terminate.

Oenopides was an ancient Greek mathematician and astronomer from the 5th century BCE, notable for his contributions to the field of astronomy and possibly geometry. He is most famously associated with the development of the concept of the zodiac and for being one of the early figures to advocate for the use of a gnomon (a device for measuring the altitude of celestial bodies) in astronomical observations. His work likely influenced later scholars, including those in the Hellenistic period.

Olivier Guimond (père) refers to a Canadian actor and comedian, known for his work in theater, television, and film. He was born on May 15, 1914, and passed away on November 23, 1971. Guimond was a prominent figure in Quebec's entertainment scene and is remembered for his contributions to the performing arts. He often performed comedy and had a significant influence on the development of humor in Quebec culture.

**Omega World Travel, Inc. v. Mummagraphics, Inc.** is a notable case that was decided by the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit in 2004. The case primarily deals with issues related to trademark law, specifically concerning the registration and use of trademarks in the travel industry. ### Case Background Omega World Travel, Inc. is a travel agency that operated under its own trademark, while Mummagraphics, Inc.

Onsager reciprocal relations are fundamental principles in nonequilibrium thermodynamics that describe the behavior of systems close to thermal and chemical equilibrium. These relations, formulated by the physicist Lars Onsager in the 1930s, express a profound symmetry in the response of a system to perturbations.

OO9 is a term often associated with a specific scale used in model railroading, specifically for narrow-gauge railways. The "OO" typically refers to the gauge of the track, which is 16.5 mm (0.65 inches) between the rails, but "OO9" specifically refers to a smaller gauge of 9 mm for narrow-gauge trains.

Open energy system models refer to computational frameworks and tools that are developed to analyze and simulate various aspects of energy systems, such as generation, distribution, consumption, and transition towards more sustainable practices. These models are typically characterized by their openness, meaning that they are publicly accessible, transparent, and often collaboratively developed.

An open reading frame (ORF) is a sequence of DNA that has the potential to be translated into a protein. It is defined as a continuous stretch of nucleotides that begins with a start codon (usually AUG) and ends with a stop codon (either UAA, UAG, or UGA) without any intervening stop codons. The presence of an ORF suggests that the corresponding RNA transcript can be translated into a polypeptide chain.

The Open Relay Behavior-modification System, commonly known as ORB, is a psychological and social framework designed to influence and modify behavior in individuals or groups. It combines principles from behavioral psychology, systems theory, and often incorporates technology and open-source methods to facilitate behavior change. While specific implementations of ORB may vary, its core components typically include: 1. **Behavioral Analysis**: Identifying specific behaviors that need to be changed or reinforced.

The Optica Fellow designation is a prestigious recognition granted by the Optica Foundation (formerly known as the Optical Society or OSA) to individuals who have made significant contributions to the field of optics and photonics. Being named an Optica Fellow acknowledges their accomplishments in research, technology, education, and service to the optics community. To be considered for this honor, candidates typically must have demonstrated outstanding achievements in areas such as innovation, leadership, and the advancement of the field.

The Ordnance Survey National Grid is a system used in Great Britain for mapping and geographical referencing. Developed by Ordnance Survey (OS), the national mapping agency for Great Britain, the National Grid provides a standardized method of identifying locations across the country. **Key features of the Ordnance Survey National Grid include:** 1. **Grid System**: The National Grid is based on a series of grid squares, each identified by a combination of letters and numbers.

OSTM/Jason-2, or the Ocean Surface Topography Mission/ Jason-2, is a satellite designed to monitor ocean surface topography, which involves measuring the height of the ocean surface from space. Launched on June 20, 2008, Jason-2 is a partnership among NASA, the French space agency CNES, and the European Organization for the Exploitation of Meteorological Satellites (EUMETSAT).

Alchemy is an ancient practice that combines elements of philosophy, chemistry, medicine, astrology, and mysticism. Here’s an outline that captures key aspects of alchemy: ### 1. **Definition of Alchemy** - Historical roots and evolution - Distinction between alchemy and modern chemistry - Goals: Transmutation, the Philosopher's Stone, immortality ### 2.

Overbelief is a term often used in various philosophical, psychological, and theological contexts to describe a belief that transcends or goes beyond rational justification, evidence, or empirical support. It implies a strong commitment to an idea or a set of ideas, often rooted in faith or deep conviction, that may not necessarily align with logical reasoning or observable reality. In psychology, overbelief can refer to convictions held by individuals that influence their perception and interpretation of experiences.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

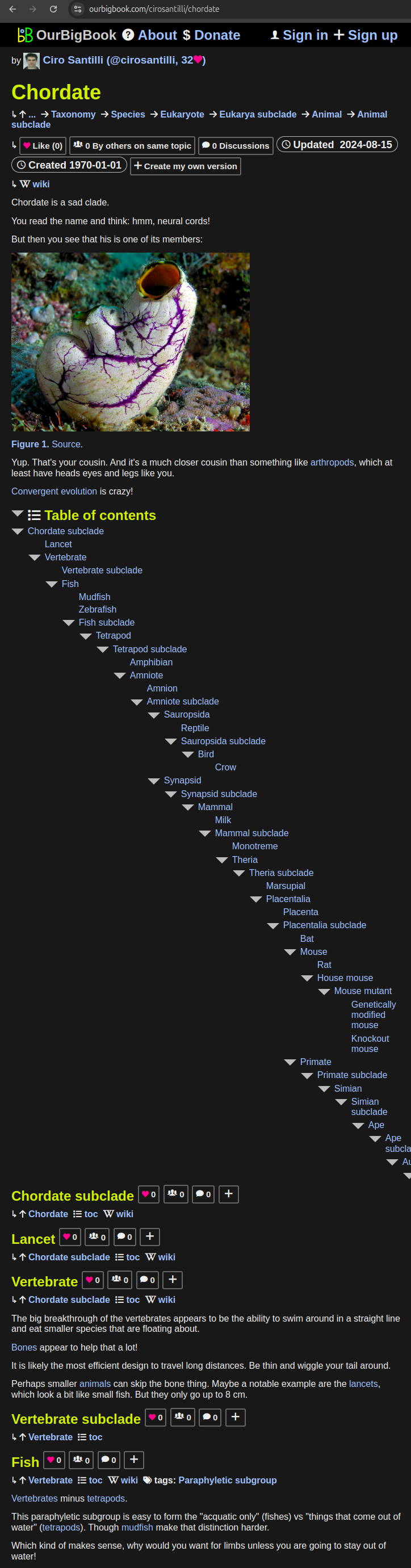

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

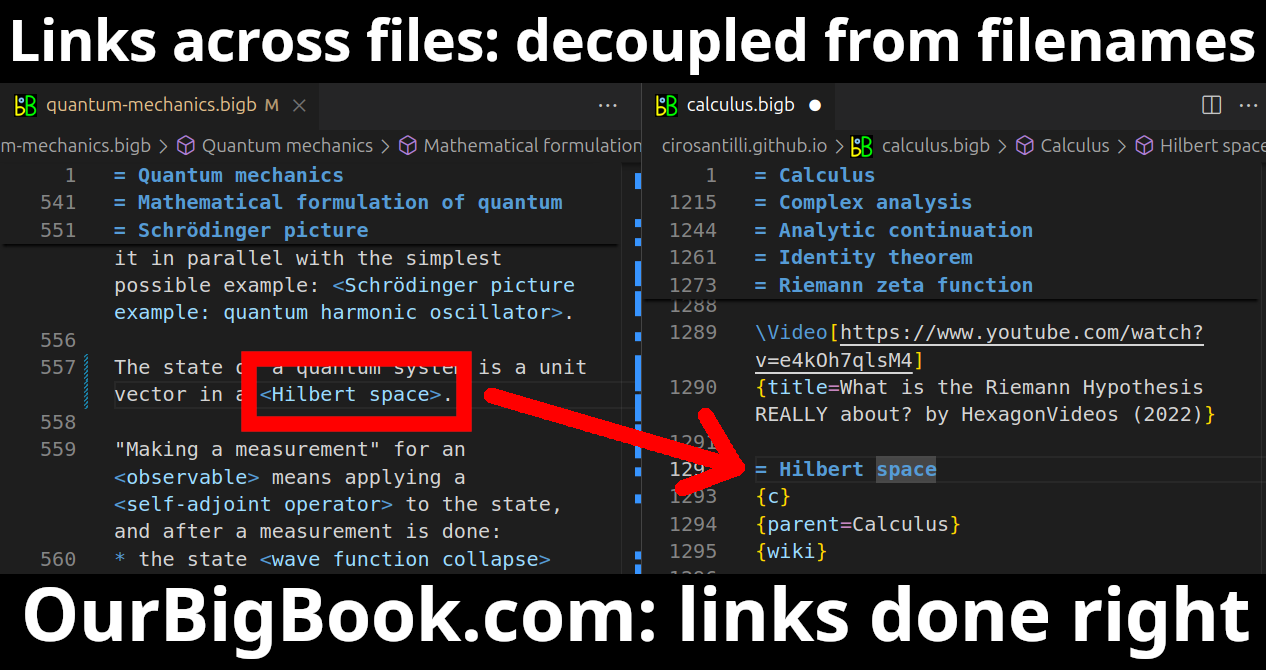

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

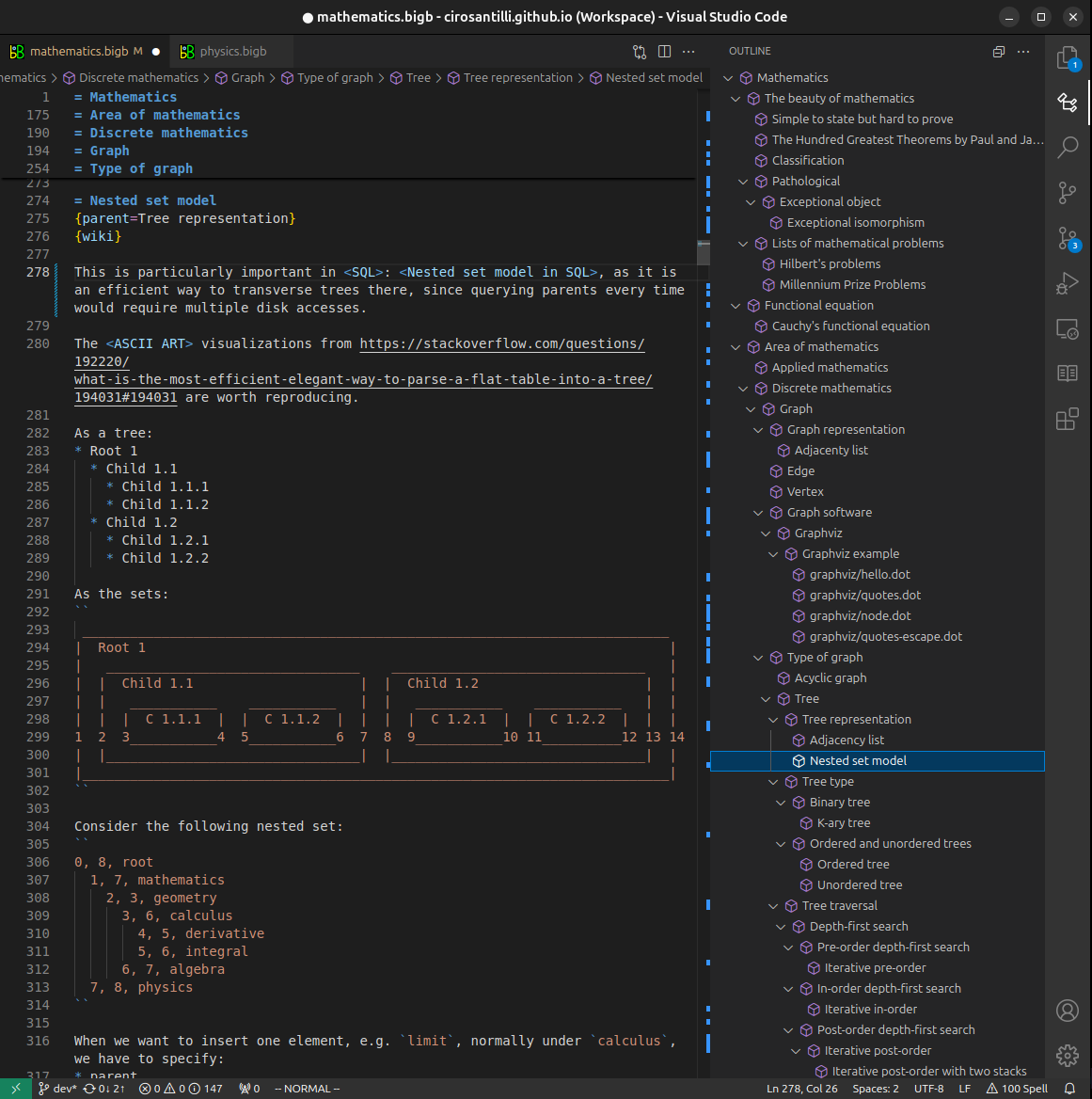

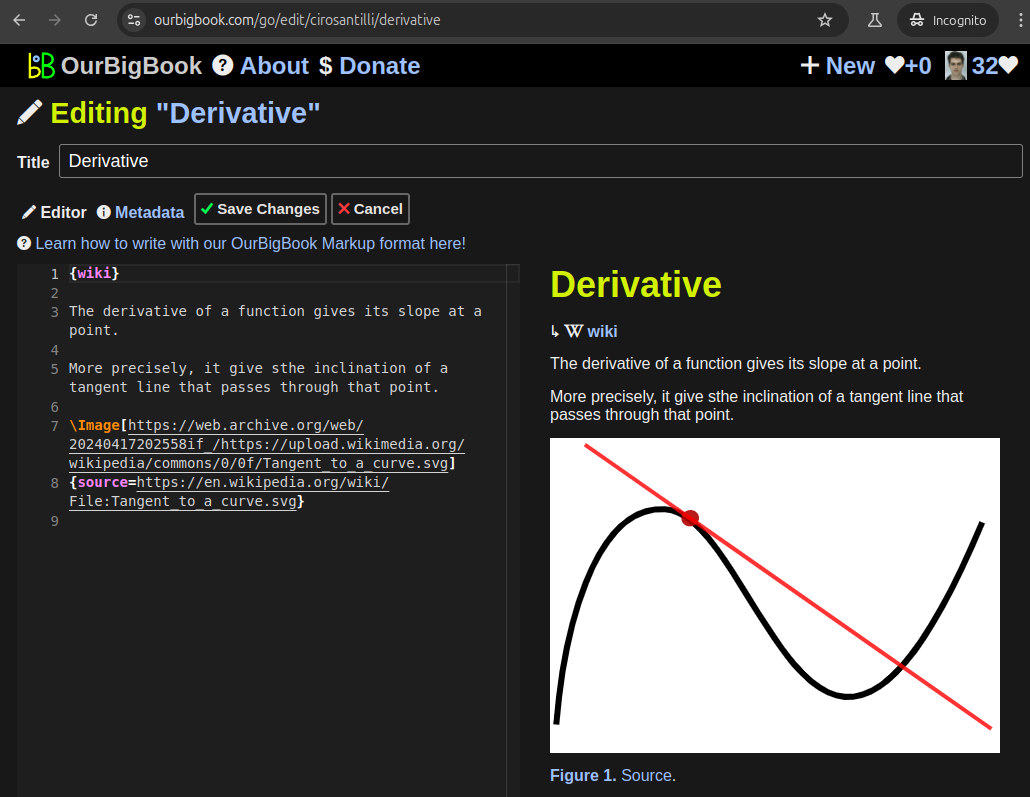

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact