The idea tha taking the limit of the non-classical theories for certain parameters (relativity and quantum mechanics) should lead to the classical theory.

It appears that classical limit is only very strict for relativity. For quantum mechanics it is much more hand-wavy thing. See also: Subtle is the Lord by Abraham Pais (1982) page 55.

Boooooring. Except for Navier-Stokes existence and smoothness. That's OK.

E. Coli Whole Cell Model by Covert Lab Time series run variant by  Ciro Santilli 37 Updated 2025-07-16

Ciro Santilli 37 Updated 2025-07-16

To modify the nutrients as a function of time, with To select a time series we can use something like:As mentioned in

python runscripts/manual/runSim.py --variant nutrientTimeSeries 25 25python runscripts/manual/runSim.py --help, nutrientTimeSeries is one of the choices from github.com/CovertLab/WholeCellEcoliRelease/blob/7e4cc9e57de76752df0f4e32eca95fb653ea64e4/models/ecoli/sim/variants/__init__.py#L5725 25 means to start from index 25 and also end at 25, so running just one simulation. 25 27 would run 25 then 26 and then 27 for example.The timeseries with index 25 is so we understand that it starts with extra amino acids in the medium, which benefit the cell, and half way through those are removed at time 1200s = 20 minutes. We would therefore expect the cell to start expressing amino acid production genes exactly at that point.

reconstruction/ecoli/flat/condition/timeseries/000025_cut_aa.tsv and contains"time (units.s)" "nutrients"

0 "minimal_plus_amino_acids"

1200 "minimal"nutrients likely means condition in that file however, see bug report with 1 1 failing: github.com/CovertLab/WholeCellEcoliRelease/issues/24When we do this the simulation ends in:so we see that the doubling time was faster than the one with minimal conditions of

Simulation finished:

- Length: 0:34:23

- Runtime: 0:08:030:42:49, which makes sense, since during the first 20 minutes the cell had extra amino acid nutrients at its disposal.The output directory now contains simulation output data under

out/manual/nutrientTimeSeries_000025/. Let's run analysis and plots for that:python runscripts/manual/analysisVariant.py &&

python runscripts/manual/analysisCohort.py --variant 25 &&

python runscripts/manual/analysisMultigen.py --variant 25 &&

python runscripts/manual/analysisSingle.py --variant 25We can now compare the outputs of this run to the default

wildtype_000000 run from Section "Install and first run".out/manual/plotOut/svg_plots/massFractionSummary.svg: because we now have two variants in the sameout/folder,wildtype_000000andnutrientTimeSeries_000025, we now see a side by side comparision of both on the same graph!The run variant where we started with amino acids initially grows faster as expected, because the cell didn't have to make it's own amino acids, so growth is a bit more efficient.

The following plots from under

out/manual/wildtype_000000/000000/{generation_000000,nutrientTimeSeries_000025}/000000/plotOut/svg_plots have been manually joined side-by-side with:for f in out/manual/wildtype_000000/000000/generation_000000/000000/plotOut/svg_plots/*; do

echo $f

svg_stack.py \

--direction h \

out/manual/wildtype_000000/000000/generation_000000/000000/plotOut/svg_plots/$(basename $f) \

out/manual/nutrientTimeSeries_000025/000000/generation_000000/000000/plotOut/svg_plots/$(basename $f) \

> tmp/$(basename $f)

doneAmino acid counts

. Source. aaCounts.svg:- default: quantities just increase

- amino acid cut: there is an abrupt fall at 20 minutes when we cut off external supply, presumably because it takes some time for the cell to start producing its own

External exchange fluxes of amino acids

. Source. aaExchangeFluxes.svg:- default: no exchanges

- amino acid cut: for all graphs except phenylalanine (PHE), either the cell was intaking the AA (negative flux), and that intake goes to 0 when the supply is cut, or the flux is always 0.

mRNA count of highly expressed mRNAs

. Source. From file expression_rna_03_high.svg. Each of the entries is a gene using the conventional gene naming convention of xyzW, e.g. here's the BioCyc for the first entry, tufA: biocyc.org/gene?orgid=ECOLI&id=EG11036, which comments Elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) is the most abundant protein in E. coli.

External exchange fluxes

. Source. mediaExcange.svg: this one is similar to aaExchangeFluxes.svg, but it also tracks other substances. The color version makes it easier to squeeze more substances in a given space, but you lose the shape of curves a bit. The title seems reversed: red must be excretion, since that's where glucose (GLC) is.The substances are different between the default and amino acid cut graphs, they seem to be the most exchanged substances. On the amino cut graph, first we see the cell intaking most (except phenylalanine, which is excreted for some reason). When we cut amino acids, the uptake of course stops.

A report on the Navier-Stokes Problem by Vladimir Šverak

. Source. 2025.Originally it was likely created to study constrained mechanical systems where you want to use some "custom convenient" variables to parametrize things instead of global x, y, z. Classical examples that you must have in mind include:lagrangian mechanics lectures by Michel van Biezen (2017) is a good starting point.

- compound Atwood machine. Here, we can use the coordinates as the heights of masses relative to the axles rather than absolute heights relative to the ground

- double pendulum, using two angles. The Lagrangian approach is simpler than using Newton's laws

- two-body problem, use the distance between the bodies

When doing lagrangian mechanics, we just lump together all generalized coordinates into a single vector that maps time to the full state:where each component can be anything, either the x/y/z coordinates relative to the ground of different particles, or angles, or nay other crazy thing we want.

Then, the stationary action principle says that the actual path taken obeys the Euler-Lagrange equation:This produces a system of partial differential equations with:

- equations

- unknown functions

- at most second order derivatives of . Those appear because of the chain rule on the second term.

The mixture of so many derivatives is a bit mind mending, so we can clarify them a bit further. At:the is just identifying which argument of the Lagrangian we are differentiating by: the i-th according to the order of our definition of the Lagrangian. It is not the actual function, just a mnemonic.

Then at:

- the part is just like the previous term, just identifies the argument with index ( because we have the non derivative arguments)

- after the partial derivative is taken and returns a new function , then the multivariable chain rule comes in and expands everything into terms

However, people later noticed that the Lagrangian had some nice properties related to Lie group continuous symmetries.

Basically it seems that the easiest way to come up with new quantum field theory models is to first find the Lagrangian, and then derive the equations of motion from them.

For every continuous symmetry in the system (modelled by a Lie group), there is a corresponding conservation law: local symmetries of the Lagrangian imply conserved currents.

Genius: Richard Feynman and Modern Physics by James Gleick (1994) chapter "The Best Path" mentions that Richard Feynman didn't like the Lagrangian mechanics approach when he started university at MIT, because he felt it was too magical. The reason is that the Lagrangian approach basically starts from the principle that "nature minimizes the action across time globally". This implies that things that will happen in the future are also taken into consideration when deciding what has to happen before them! Much like the lifeguard in the lifegard problem making global decisions about the future. However, chapter "Least Action in Quantum Mechanics" comments that Feynman later notice that this was indeed necessary while developping Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory into quantum electrodynamics, because they felt that it would make more sense to consider things that way while playing with ideas such as positrons are electrons travelling back in time. This is in contrast with Hamiltonian mechanics, where the idea of time moving foward is more directly present, e.g. as in the Schrödinger equation.

Genius: Richard Feynman and Modern Physics by James Gleick (1994) chapter "The Best Path" mentions that Richard Feynman didn't like the Lagrangian mechanics approach when he started university at MIT, because he felt it was too magical. The reason is that the Lagrangian approach basically starts from the principle that "nature minimizes the action across time globally". This implies that things that will happen in the future are also taken into consideration when deciding what has to happen before them! Much like the lifeguard in the lifegard problem making global decisions about the future. However, chapter "Least Action in Quantum Mechanics" comments that Feynman later notice that this was indeed necessary while developping Wheeler-Feynman absorber theory into quantum electrodynamics, because they felt that it would make more sense to consider things that way while playing with ideas such as positrons are electrons travelling back in time. This is in contrast with Hamiltonian mechanics, where the idea of time moving foward is more directly present, e.g. as in the Schrödinger equation.

And partly due to the above observations, it was noticed that the easiest way to describe the fundamental laws of particle physics and make calculations with them is to first formulate their Lagrangian somehow: S.

TODO advantages:

- physics.stackexchange.com/questions/254266/advantages-of-lagrangian-mechanics-over-newtonian-mechanics on Physics Stack Exchange, fucking closed question...

- www.quora.com/Why-was-Lagrangian-formalism-needed-in-the-presence-of-Newtonian-formalism

- www.researchgate.net/post/What_is_the_advantage_of_Lagrangian_formalism_over_Hamiltonian_formalism_in_QFT

Bibliography:

- www.physics.usu.edu/torre/6010_Fall_2010/Lectures.html Physics 6010 Classical Mechanics lecture notes by Charles Torre from Utah State University published on 2010,

- Classical physics only. The last lecture: www.physics.usu.edu/torre/6010_Fall_2010/Lectures/12.pdf mentions Lie algebra more or less briefly.

- www.damtp.cam.ac.uk/user/tong/dynamics/two.pdf by David Tong

Euler-Lagrange equation explained intuitively - Lagrangian Mechanics by Physics Videos by Eugene Khutoryansky (2018)

Source. Well, unsurprisingly, it is exactly what you can expect from an Eugene Khutoryansky video.Author: Michel van Biezen.

As mentioned on the Wikipedia page en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Stationary_Action_Principle&oldid=1020413171, "principle of least action" is not accurate since it could not necessarily be a minima, we could just be in a saddle-point.

Calculus of variations is the field that searches for maxima and minima of Functionals, rather than the more elementary case of functions from to .

Let's start with the one dimensional case. Let the and a Functional defined by a function of three variables :

Then, the Euler-Lagrange equation gives the maxima and minima of the that type of functional. Note that this type of functional is just one very specific type of functional amongst all possible functionals that one might come up with. However, it turns out to be enough to do most of physics, so we are happy with with it.

Given , the Euler-Lagrange equations are a system of ordinary differential equations constructed from that such that the solutions to that system are the maxima/minima.

By and we simply mean "the partial derivative of with respect to its second and third arguments". The notation is a bit confusing at first, but that's all it means.

Therefore, that expression ends up being at most a second order ordinary differential equation where is the unknown, since:

Now let's think about the multi-dimensional case. Instead of having , we now have . Think about the Lagrangian mechanics motivation of a double pendulum where for a given time we have two angles.

Let's do the 2-dimensional case then. In that case, is going to be a function of 5 variables rather than 3 as in the one dimensional case, and the functional looks like:

This time, the Euler-Lagrange equations are going to be a system of two ordinary differential equations on two unknown functions and of order up to 2 in both variables:At this point, notation is getting a bit clunky, so people will often condense the vectoror just omit the arguments of entirely:

Calculus of Variations ft. Flammable Maths by vcubingx (2020)

Source. These are the final equations that you derive from the Lagrangian via the Euler-Lagrange equation which specify how the system evolves with time.

Basically: S.

Pinned article: Introduction to the OurBigBook Project

Welcome to the OurBigBook Project! Our goal is to create the perfect publishing platform for STEM subjects, and get university-level students to write the best free STEM tutorials ever.

Everyone is welcome to create an account and play with the site: ourbigbook.com/go/register. We belive that students themselves can write amazing tutorials, but teachers are welcome too. You can write about anything you want, it doesn't have to be STEM or even educational. Silly test content is very welcome and you won't be penalized in any way. Just keep it legal!

Intro to OurBigBook

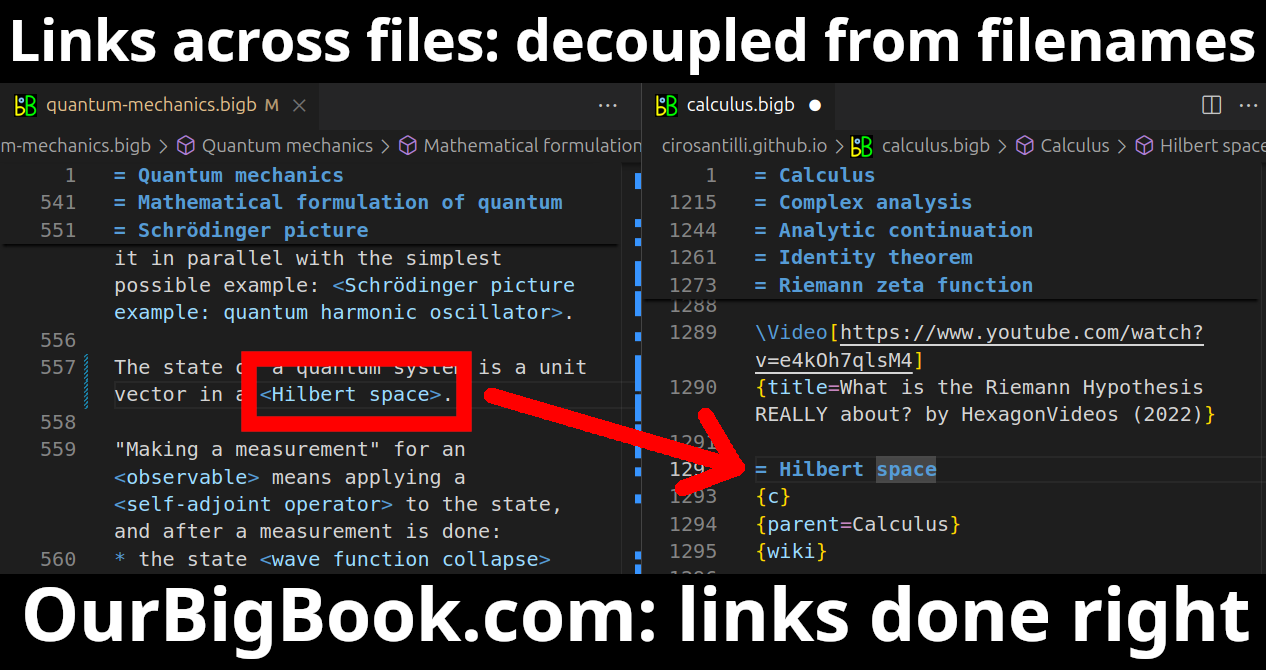

. Source. We have two killer features:

- topics: topics group articles by different users with the same title, e.g. here is the topic for the "Fundamental Theorem of Calculus" ourbigbook.com/go/topic/fundamental-theorem-of-calculusArticles of different users are sorted by upvote within each article page. This feature is a bit like:

- a Wikipedia where each user can have their own version of each article

- a Q&A website like Stack Overflow, where multiple people can give their views on a given topic, and the best ones are sorted by upvote. Except you don't need to wait for someone to ask first, and any topic goes, no matter how narrow or broad

This feature makes it possible for readers to find better explanations of any topic created by other writers. And it allows writers to create an explanation in a place that readers might actually find it.Figure 1. Screenshot of the "Derivative" topic page. View it live at: ourbigbook.com/go/topic/derivativeVideo 2. OurBigBook Web topics demo. Source. - local editing: you can store all your personal knowledge base content locally in a plaintext markup format that can be edited locally and published either:This way you can be sure that even if OurBigBook.com were to go down one day (which we have no plans to do as it is quite cheap to host!), your content will still be perfectly readable as a static site.

- to OurBigBook.com to get awesome multi-user features like topics and likes

- as HTML files to a static website, which you can host yourself for free on many external providers like GitHub Pages, and remain in full control

Figure 3. Visual Studio Code extension installation.Figure 4. Visual Studio Code extension tree navigation.Figure 5. Web editor. You can also edit articles on the Web editor without installing anything locally.Video 3. Edit locally and publish demo. Source. This shows editing OurBigBook Markup and publishing it using the Visual Studio Code extension.Video 4. OurBigBook Visual Studio Code extension editing and navigation demo. Source. - Infinitely deep tables of contents:

All our software is open source and hosted at: github.com/ourbigbook/ourbigbook

Further documentation can be found at: docs.ourbigbook.com

Feel free to reach our to us for any help or suggestions: docs.ourbigbook.com/#contact